The concept of “evil” presents a unique challenge when viewed through the lens of Daoism, particularly as expressed in Laozi’s Tao Te Ching. Unlike philosophies that posit evil as a fundamental opposing force to good, or define it primarily through the lens of suffering it causes, Daoism tends to view good and evil as relative concepts, interdependent parts of a larger, natural whole – the Dao. Understanding this perspective requires moving beyond dualistic thinking and embracing the principles of balance, relativity, and the natural flow of existence.

The Relativity of Good and Evil

Laozi famously points out the interdependent nature of opposites in Chapter 2 of the Tao Te Ching:

“When everyone under heaven knows beauty as beauty, There is ugliness. When everyone knows good as good, There is evil.”

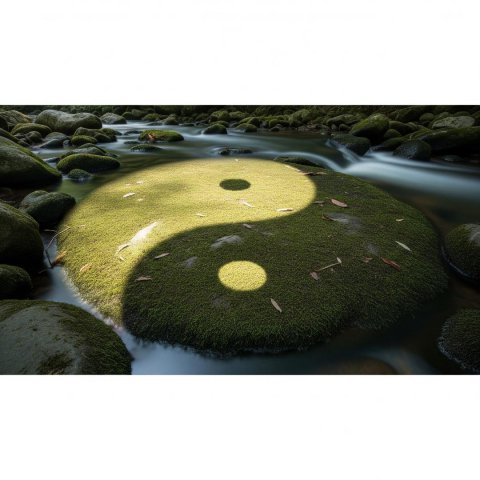

Laozi is suggesting that our concepts of “good” and “evil” are human constructs, arising from comparison and judgment. One cannot exist without the other; they define each other. Like Yin and Yang, they are two sides of the same coin, aspects of the dynamic interplay that constitutes reality. The Dao itself, the ultimate source and principle of all things, is beyond such distinctions. It is the uncarved block, containing all potentials but not defined by them. Therefore, from the perspective of the Dao, labeling something as absolutely “evil” is a limited human judgment based on a specific viewpoint or desired outcome. What appears harmful or disruptive from one angle might be a necessary part of a larger balancing process from another.

Disharmony, Not Absolute Evil

Rather than focusing on inherent “evil,” Daoism often addresses what we might perceive as evil in terms of disharmony, imbalance, or deviation from the natural Way (Dao). Actions or situations perceived as evil often arise when individuals or systems operate out of alignment with the natural flow, driven by excessive desire, forced action, or unnatural striving (Wei). This is where your distinction between “causal” and “consequential” evil might be interpreted through a Daoist framework: the cause is the deviation from the Dao (imbalance, excessive desire), and the consequence is the resulting suffering, conflict, or misfortune that we label as evil. However, Daoism emphasizes that even these consequences are part of the natural process of correction and return to balance.

Daoism and Suffering

While Daoism certainly acknowledges suffering, it doesn’t equate suffering directly with “evil” in the way some other traditions might. Suffering is seen as an inevitable part of life’s cycles, often arising from attachment, resistance to change, and clinging to judgments (like rigidly defining things as good or bad). The path advocated is not necessarily to eliminate all suffering (an impossible task) but to understand its roots in our own perceptions and reactions, and to cultivate acceptance and detachment, thereby minimizing its grip. By aligning with the Dao and practicing Wu Wei (effortless action, non-striving), one reduces the internal conflict and resistance that amplifies suffering.

Dealing with “Evil”: The Path of Wu Wei

How, then, does Daoism suggest dealing with situations or actions perceived as evil? The primary approach is rooted in the principle of Wu Wei. This is often misinterpreted as passive inaction, but it more accurately means acting in harmony with the natural flow, without force or ego-driven agendas.

- Non-Contention (Bu Zheng): The Tao Te Ching repeatedly advises against meeting force with force or aggression with aggression. Chapter 68 states: “The best warrior is never aggressive.” Directly opposing “evil” often strengthens it or creates further imbalance and unintended consequences. Instead, the approach is one of yielding, flexibility, and patience, like water wearing away rock.

- Understanding and Perspective: Rather than immediate condemnation, the Daoist approach encourages understanding the underlying causes of the disharmony. What imbalance led to this situation? What natural principle is being violated?

- Cultivating Virtue (De): The focus is often internal. By cultivating one’s own virtue – simplicity, humility, compassion, non-interference – one aligns oneself with the Dao. A person centered in the Dao naturally contributes to harmony and acts as a balancing influence without needing to directly “fight evil.” The Sage leads by example and presence, not by imposing rules or judgments.

- Allowing Natural Resolution: Daoism trusts the self-regulating nature of the Dao. Often, the wisest course is to allow situations to unfold naturally, intervening subtly and only when necessary, guiding things back towards balance rather than forcing a specific outcome. Patience is key; the Dao’s cycles may operate on timescales beyond immediate human comprehension.

However, Wu Wei, a term we use often in Taiji, is not passivity; rather, it is not forcing. It means acting appropriately according to the situation and the moment, without unnecessary force, ego, or striving against the grain of how things actually are.

In a situation where your life is directly threatened, though, the natural and appropriate response, aligned with the fundamental instinct for survival (which is part of the Dao), may well be decisive self-defense. As my Master told us, when you must fight, just fight. Daoist principles strongly caution against initiating conflict, acting out of aggression, or seeking to dominate. However, responding to a direct, unprovoked attack is different. Defending yourself is an attempt to restore immediate balance and preserve the natural state (your life). It’s an action arising from the situation, not imposed upon it by ego or desire.

Even in self-defense, the Daoist ideal would lean towards using only the minimum force necessary to neutralize the threat and ensure safety. The goal is preservation and restoration of balance, not punishment, revenge, or excessive violence. Think of the fluid, yielding, yet effective movements in internal martial arts like Taijiquan (which has roots in Daoist philosophy) – they redirect and neutralize force rather than meeting it head-on with brute strength, using only what is needed.

While difficult in crisis, the ideal Daoist mindset during such an event would strive to remain as centered as possible, acting out of necessity rather than panic, hatred, or rage. The action is performed because it must be, to restore safety.

“This emphasis on non-contention and yielding does not, however, imply helplessness in the face of direct physical threat. Daoism acknowledges the reality of danger and the natural instinct for self-preservation. Wu Wei translates to ‘appropriate action,’ and when confronted with immediate harm, the appropriate action may indeed be self-defense. This is not seen as aggression initiated by ego, but as a spontaneous (Ziran) response necessary to restore immediate balance and preserve life. The ideal, however, remains rooted in Daoist principles: using only the minimal force necessary to neutralize the threat, acting defensively rather than out of malice or rage, and aiming solely to restore safety. It is the difference between a forceful reaction born of panic and a centered, necessary response to immediate imbalance.”

Daoism offers a profound and challenging perspective on evil. It reframes it not as an absolute force but as a relative concept arising from human judgment and indicative of disharmony within the natural order. By understanding the interdependence of opposites (Yin/Yang) and recognizing that “good” and “evil” are two sides of the same coin, we can move beyond simplistic dualism. The Daoist way of dealing with perceived evil is not through direct confrontation or moralistic crusades, but through the subtle, powerful practice of Wu Wei: aligning oneself with the Dao, cultivating inner virtue, acting with flexibility and non-contention, and trusting the ultimate balancing nature of the Way. It is a path that seeks harmony not by eliminating perceived darkness, but by understanding its place within the greater light of the Dao.