American Ballet Theater's Lady of the Camellias

Premiere of John Neumeier's Choreography

By: Susan Hall - May 28, 2010

Lady of the Camellias

American Ballet Theater

Metropolitan Opera House, New York

Company premiere

Choreography by John Neumeier

after the novel by Alexander Dumas fils

Music by Frederic Chopin

Staged by Keith Hagen and Victor Hughes

Scenery and costumes by Jurgen Rose

Lighting concept by John Neumeier

Lighting reconstructed by Ralf Merkel

Julie Kent as Marguerite Gautier

Roberto Bolle as Armand Duval

Gillian Murphy as Manon Lescaut

David Hallberg as Des Grieux

May 25 through June 7

Choreographer John Neumeier's Lady of the Camellias, with music selected from Frederic Chopin's work, had its American Ballet Theater premiere this week. Neumeier has poured vision, passion and detail into the now classic Dumas fils story of the mid nineteenth century Parisian courtesan who falls in love with a younger man. and then magnanimously gives him up.

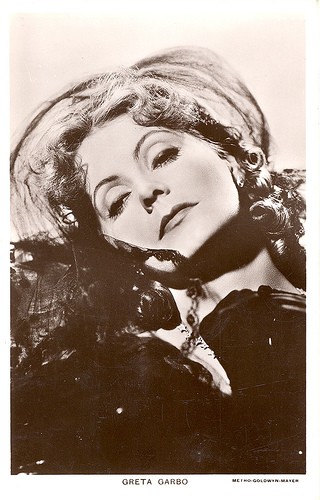

The story based on the Lady has legs. Verdi picked it up for La Traviata, Sir Frederick Ashton choreographed it. Movies have been made. Even the elusive Garbo took a turn in the role. The staying power of the story is clear, perhaps because doomed love is a central theme in human history.

The Neumeier Lady of the Camellias had its premier in Stuttgart in 1978 and was performed by the Stuttgart Ballet at the Kennedy Center the next year At last it has arrived at the American Ballet Theater.

Chopin composed polonaises, mazurkas and waltzes, but he did not compose for the ballet. His dreaminess, his fire and spirit are searching accompaniments to this production.

Neumeier is a story teller who uses all available devices. He chooses to start as Dumas did, at an auction of the courtesan Marguerite’s belongings. In a prologue, her young lover, danced by Roberto Bolle, rushes in and collapses, remembering their passionate romance and her tragic end. A narrator carries the overarching story, as Marguerite's personal belongings, a robe or a playbill, trigger trips down memory lane.

The montages root the timeless story in the present and are told in a combination of gesture and dance. Even the gestures that move the story forward are given wing by the dancers. These vignettes illustrate the events of Marguerite's life and, even more importantly, the feelings of the principals.

Cougars are in today, but in the real world, they do not abound. Demi Moore of megabucks continues to keep Ashton Kutcher interested. Lillian Vernon succeeded in holding on to her hair stylist Pablo, treating him to his own hair salon. Decades ago, Nina Foch, the actress, paid for her young husband's medical school and then he dumped her. And so on back through history. Colette loved young men. Great novelist George Elliot drove her much younger second husband to jump into the canals of Venice to get away from her sexual advances. If women have the bucks, they can do just what old men do for their teen trophies. In Lady of the Camellias, Marguerite supports her lover Armand until the money runs out. If she'd been healthier, she might have held the auction mid-story to keep the money and the relationship flowing a bit longer.

Neumeier's work is plotted and operatic. Emotions, plotline and movement respond to the music. The Chopin selections used in this ballet are often on point, and apt for the storyline. Neumeier's preoccupation with bringing his works into the present can be glimpsed not only in the dance, but in the actual performance of the music by a pianist on stage with the dancers.

We early on see Marguerite at a ballet based on Manon Lescaut, a scandalous book by the Abbe Prevost published in 1700 and immediately banned. Neumeier chooses to keep the relationship of Manon and the chevalier des Grieux parallel. Just as the auction provides a jumping off to an almost fantasy telling of Marguerite's life, so does the performance of Manon that Marguerite attends provide a jumping off point to the fantasy of Manon's ill-fated relationship. The parallels are not precise, but Neumeier focuses on the perils of passion in both relationships.

It's ironic that since the early nineteenth century, ballerinas have been superior to their dancing porters. On stage the women dominate, but in the story, men are the kingpins.

Marguerite and Armand emotionally carry the ballet, but their fictive parallel gets more dramatic moves, the faster beats, and higher leaps. Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg as the Manon couple are delicious, and Marguerite's effort to join with them as they go into the Louisiana marshes is touching. The most demanding pas de deux moments happen between the fantasy couple.

Julie Kent and Roberto Bolle as Marguerite and Armand carry the story forward, walking and dashing around the stage. Bolle has a moving eloquence rather than higher leaps and faster beats. Even his difficult steps come out of the emotions and feelings of his character. Harmony for Bolle is the matching of feeling and movement. His nickname "Italian Stallion" hardly conveys his erotic charge. Bolle as danseur noble is perfect for this expressive role, even though one wished for more explosive moves.

Bolle's big break came when retiring ballerina Alessandra Ferre picked him as her partner in her farewell performances. She wanted to make her retirement special and introducing this spectacular new talent would overcome the sadness of the moment. Sounds like a solution Marguerite and Manon might well have deployed. The Marschallen does it so well in Rosenkavalier.

Does Neumeier display his 'dark' reputation? His Little Mermaid had one of her new human limbs grotesquely contorted over her shoulder. In his Odyssey men in gold thongs imitated pigs. Lady is a dark story lightened by Kent and Bolle's performance and the dynamics of the parallel Manon story. The nude sex scenes tucked into one side of the stage and also at the rear, are effective and contribute to the sense that passion drives this story. The Met stage comes direct from opera productions which are a hotbed of nudity and sex.

Neumeier forecasts the tragic end of his ballet, but he also uses the Manon couple to reinforce the images of passion, of beauty. He shows how timeless ballet can elevate even a doomed relationship to moments of joy. Joy at least for the viewer watching Bolle and Kent at work.

Lest you think the performers are not caught up in the emotions Neumeier choreographs, Julie Kent's eyes were filled with tears at the end. Bolle is known for his acting ability, but the cool, long-stemmed beauties do not always show their insides as they display their athletic ability, Kent’s emotional presence makes Neumeier's point clear. Ballet can tell big stories on an operatic scale. Timeless tales can be present.