Celebrated early in his career as a pre-eminent architectural renderer or illustrator, Hugh Ferris (1889-1962) was also a visual poet in the service of a gargantuan urban utopia. His interpretation of the skyscraper and its role in popular culture influenced a generation of architects, futurists, and artists.

Vibrant examples of his vision can still be found throughout popular culture. A sampling: Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, Batman’s Gotham City, the backdrops for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Superman’s Metropolis, Kerry Conran’s “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow,” the ’40s LA backdrop for Boston Blackie and other Noir thrillers, and pictorials for 1981’s Escape from New York. The graphic novels filled with visual resonances to Ferriss are too numerous to mention.

Of course, parallel to Ferriss’ career there occurred a dramatic shift in building design, a move away from traditional forms, decorative details, and construction methods. The Modern Movement, including Art Deco, Art Moderne, and fresh International styles, inspired the transformation, which was born in Europe and spread to America during the latter half of the ’20s. The 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Decoratifs advocated Art Deco and Art Moderne styles. Their sleek, sharp-edges were visually punctuated with distinctive, simplified details. The smooth surfaces of Art Deco morphed into the streamlined yet less decorative pictorials of Art Moderne.

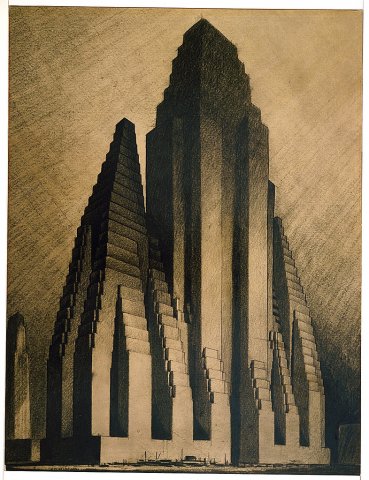

Ferriss was no doubt influenced by these European accomplishments, but he added a few of his own distinctive stylistic ingredients, creating a unique illustrative pallet. His heroic skyscrapers had a number of ancestors. For example, there is evidence in his drawings of Aztec and Mayan cultural sources, as well as resonances with Egyptian and Babylonian structures. Many of Ferriss’ skyscrapers incorporate pyramidal and temple motifs as well.

Despite his debts to the past, Ferriss was an American original, rejecting the conventional approach to architectural rendering epitomized by the highly detailed and usually colorful — but straightforward and unemotional — Beaux Arts technique. His deft touch with shadow and light, often complicated by plenty of fog or mist, added enormous dynamic tension to his sculptural drawings. He expressed an inspiring future through awesomely imaginative structural configurations.

Over the years, the term Paper Architect has become a pejorative term for academic or theoretical practitioners whose designs are never built or who never designed anything of significance. This description fits Ferriss’ architectural career in a mundane sense. But there is a powerful difference between Ferriss and other “paper architects.” He may never have designed a substantial building project, but his drawings of super-soaring skyscrapers, threatening yet wondrous, influenced urban structural design for a significant part of the 20th century and beyond. He is America’s master of architectural graphic representation.

Ferriss was born in St. Louis, Missouri and educated as an architect at Washington University. After arriving in New York City in 1912, he was soon employed as a delineator for the well known architect Cass Gilbert. Among Ferriss’ earliest drawings are some of Gilbert’s Woolworth Building; in these illustrations he had not yet developed his signature manner — dark and moody.

In 1915, Ferriss left the firm and set up his own practice as an architectural delineator. By 1920, he had begun to establish his signature style. Frequently, he presented his buildings at night — as if they had been photographed in soft focus. Over the years he refined his technique, recognizing that shadows cast by and on buildings could be as visually important as the revealed surfaces.

Eliciting emotional, almost visceral, responses from viewers, his work was soon regularly featured in a wide range of publications, including Century Magazine, The Christian Science Monitor, Harper’s Magazine, and Vanity Fair. Also, Ferriss’ theoretical and philosophical writings also began to appear in various publications.

Often suppressing detail for the sake of creating a striking ambiance, Ferriss drew pictures of buildings shrouded in dark and brooding mist. His massive forms were inevitably theatrical, architecture intended to be spectacular and assertive. His powerful structures are surrounded in fog, yet the use of light and shadow emotionally heightens the impression.

Ferriss could skillfully weave his personal artistic sensibility into architectural structures. Most often his approach was to start with a realistic and precise initial drawing, but he went on to deconstruct and simplify it; his goal was to come up with a rough and impressionistic rendering. At other times he would limit layouts to the general forms and work up the tonal composition before completing the image by adding dramatic detail.

Ferriss could trick the eye to see, at the same time, both the skyscraper’s base at street level and the structure’s top pinnacle. The building’s midsection would cleverly melt away into the background. He also applied bright light at the base to emphasize the silhouette of a building’s tower. All of these techniques resulted in a miraculous fusion of the concrete and the mysterious.

Ferries was particularly skilled at rendering monumental stone and concrete forms. His illustration of the Hoover Dam forcefully emphasizes the structure’s unusual geometry, highlighting the drama of its abstract form. Also, his sketches generate the grand, heroic atmosphere of gigantic construction projects. In this sense, his adroit use of scale was the perfect compliment for his manipulation of light and shadow.

In 1929, Ferris published The Metropolis of Tomorrow. This fascinating book contains Conté Crayon sketches of tall buildings. Some of the drawings are theoretical studies; others were renderings for other architect’s skyscrapers. At the end of the book there’s a sequence of masterly views of Manhattan. Ironically, his thoughtful commentary in the volume expresses an ambivalence about the rapid urbanization of America. This notion seems to be a critical response to his own hyperbolic celebration of the urban skyscraper. But perhaps he was just hungry for geometric balance and strategic focal points.

Ferriss’ achievement has not been forgotten. For example, there is the annual Hugh Ferriss Memorial Prize, which is given out each year by the American Society of Architectural Perspectivists (ASAP). Few, if any, of the winners have approached the visual prophetic brilliance of the award’s namesake.