Route of the Maya: Part Five

Belize

By: Zeren Earls - May 31, 2016

Continuing our overland journey from Yaxha for about 45 minutes, we reached the Belize border. All the bags that were placed on a luggage rack on the roof of the bus had to be unloaded during passport control and reloaded again. When we reached Belize City on the Caribbean shore, the weather felt considerably warmer than in Guatemala.

The city was quiet and most stores closed as we headed to the seashore after arriving on a late Sunday afternoon. Mounted on the seawall, giant letters arranged from cool blue to deep orange spelled out BELIZE, welcoming all visitors. Nearby a large poster identified the ethnic groups in Belize in descending order of population – mestizo, African, Creole, Maya, Garifuna, Mennonite, East Indian, Lebanese, mixed ethnicity, Asian, Caucasian and Hindu – for a grand total of 360,000 inhabitants. At only 30,000, the Mayans in Belize constituted the smallest indigenous group of all Central American countries. This rich ethnic mix was evident among those gathered at a nearby pupusa stand and at a children’s playground. Signs on many restaurants and supermarkets in turn indicated Chinese ownership.

The shoreline turned into a silhouetted panorama as the sun went down behind buildings and trees, thus completing our full day. We then departed for the Radisson Fort George Hotel for the final two nights of our main trip ending in Belize. At the hotel with a view of the Caribbean, we enjoyed dinner that featured red snapper as entrée and sweet potato for dessert from a Creole recipe.

The next morning we journeyed to the ruins of Lamanai (a Yucatec Maya word meaning “submerged crocodile”) accessible by water transport. During a ride to Orange Walk Town to catch a prearranged boat, our local guide provided us with background information about his country. Belize was originally settled by British buccaneers, who were attracted to the coastline for shipping out mahogany logs. In 1763 the loggers were granted sovereignty by the Spanish Crown, receiving the land which is now Belize. Despite the agreement, Britain and Spain continued to wage war; in 1862 the victorious British changed the status of the area from settlement to colony, including the establishment of a sugar plantation at Indian Church (Lamanai), built on a spot where a Mayan temple once stood. The colonial land bore the official name "British Honduras" until 1973; Britain granted independence in 1981. Guatemala has long had a territorial claim on Belize; the case is still under consideration in the International Court in The Hague.

According to one theory, the word “Belize" is a misspelling of the Mayan word bolus, meaning “land of muddy water". The country, comprised of 200 islands resulting from volcanic eruption along with the strip on the mainland, offers excellent fishing and scuba diving. Its top industry is tourism, attracting people to the sun and sea, followed by exports of sugar cane, molasses, and rum mostly to Europe, and citrus fruit to the US. The real estate market attracts many foreign retirees. Drilling for offshore oil, which was found in 2005 and is refined in Venezuela, produces income as well.

All 200 islands are resorts. Belize citizens are therefore very protective of their land, roads are deliberately kept unpaved, and there is a limit on the number of people allowed to visit archaeological sites. Although there are mahogany plantations, logs may not be exported and are only for local use. The national tree in fact is the mahogany, which appears as the central emblem on the Belizean flag.

Following this informative introduction, we arrived at the dock to board a tented boat waiting for us. During a 26-mile scenic ride north to Lamanai on the banks of the New River lagoon, we saw clouds mirrored in shimmering waters even as egrets, cormorants, and herons crowded trees and mangroves along the shore. We did not see any freshwater crocodiles in the river or on the banks as I had hoped, since the name “Lamanai" meaning "submerged crocodile" had been inspired by their presence.

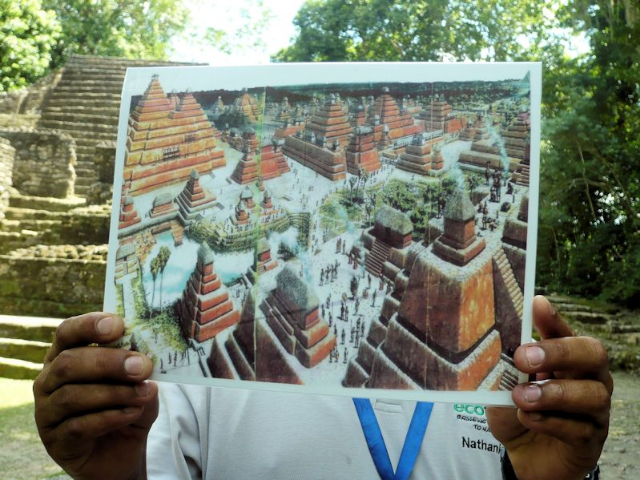

The Lamanai ruins are located within a subtropical forest. The Maya lived here for over 3000 years, from 700 BC through colonial times into the 20th century. Archaeological excavations, which began in the 1970s under David Pendergast of the Royal Ontario Museum, continued through 1988. The current project, focusing on artifacts, is co-directed by Dr. Elizabeth Graham from the Institute of Archaeology at University College London and Dr. Scott Simmons from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Major excavations will resume when additional funding is available.

Our tour began at the Mask Temple, dating from the Middle to the Late Classic Period. It is adorned by two 13-foot-high carved limestone masks of an ancient Mayan king, bearing a head dress representing a crocodile. The mask on the left side (facing the temple) is covered for protection. Two tombs dating from the 5th century have been discovered in the temple. One of the burials was encased with a “cocoon” of wood, textiles, and plaster.

The 108-foot-tall High Temple is the tallest structure at the site. It is also the second-largest temple in the Maya world from the pre-Classic period, dating from 100 BC. Several jade and shell offerings were discovered here. I was able to climb to the top of the temple, which afforded great views of the lagoon and the surrounding jungle; seen from the summit, it was fun to look at people photographing the climbers from the ground level.

The site also features the Jaguar Temple, which dates back to 625 AD. Named after its square-based jaguar decoration, the temple is partially underground. All these temples were sacred and accessed only by elite rulers and priests for important rituals. They climbed the temples with much dignity and reverence, possibly on their hands and knees as a sign of respect to the deities they were about to worship.

A chorus of howling monkeys was a delightful surprise as we walked about in the forest. Monkeys howl at the sight or sound of other monkeys, predators, people, or anything threatening. They howl back and forth at each other, assessing the strength of another troupe. Signs throughout the forest reminded visitors not to howl at the monkeys so as not to disturb their natural feeding and resting cycle. Other than mahogany and its role in the economy, history, and flag iconography, the national symbols of Belize are the black orchid, the billed toucan, and the tapir, all of which are found in the forest.

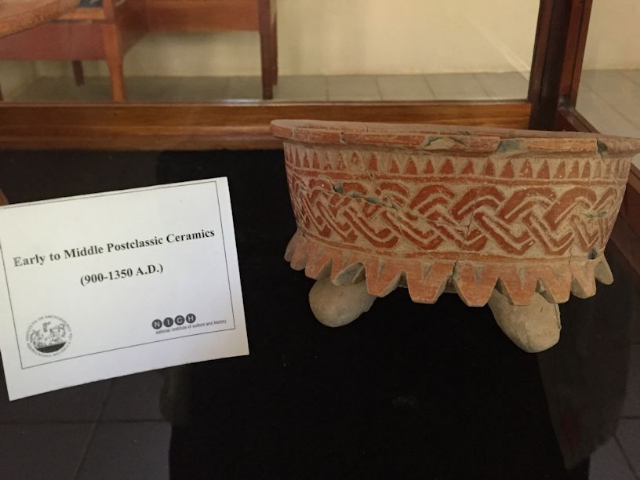

Our final visit in Lamanai was to a small on-site museum of local artifacts used in worship and daily life, providing a historical overview of what was a sophisticated Mayan civilization. Following lunch, we took the boat back to prepare for our departure to Managua.

Over a farewell dinner in Belize City, we bid goodbye to four people in the group who were returning home to US; the remaining twelve flew to Managua the following day for an added trip to Nicaragua.

(To be continued)