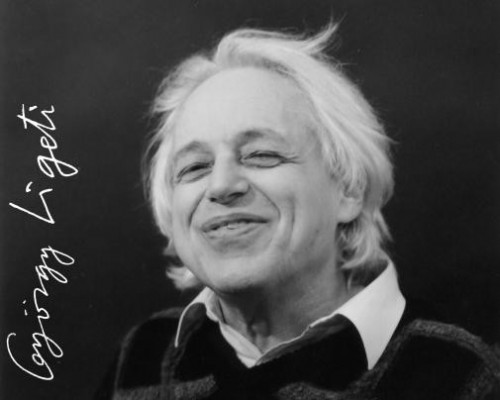

New York Philharmonic with Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre

Alan Gilbert Conducts as Doug Fitch Weaves His Magic

By: Susan Hall - Jun 01, 2010

Le Grand Macabre

by Gyorgy Ligeti

New York Philharmonic

Alan Gilbert, Conductor

Doug Fitch, Director and Designer

Edouard Getaz, Producer

Production Created by Giants are Small

Cast: Mark Scholwater, Jennifer Black, Renee Tatum, Eric Owens, Melissa Parks, Wilbur Pauley

Le Grand Macabre arrived in for its New York premier at Avery Fisher Hall. Philharmonic conductor Alan Gilbert in his first year as Music Director of the Orchestra had expressed one wish for the production: that it be sold out. Le Grand Macabre was and it deserved to be.

Gilbert took on the opera’s broad soundscape, counting on the Orchestra, which he repeatedly reminds us ‘can do anything.’ Still difficult to believe that the orchestra started rehearsing this piece of infinite and unusual variety just three days before its first performance. Having watched the impish brass section perform on its own, they probably got as much pleasure as they dished or blared out in the opera.

Ligeti’s music merges brash brass fanfares with anxious string buzzings. He adds car horns, doorbells and gunshots to the percussion. In the back of hall was a siren. The orchestra pulled off the challenging work with blasts and beauty.

Regulars at the Philharmonic look to Glenn Dicterow’s chair for a clue to the concert master’s feelings. He can be a no show when he doesn’t like a piece. But there he was in his chair for the Ligeti, often laughing when he was not performing with gusto.

The orchestra was not lit on stage, but they were not in the dark. Serving as accents as the performance began and, when the orchestra's role expanded, evoking Ligeti’s sound clouds and liturgical effects often to other worldly effect.

Le Grand Macabre was billed by the Philharmonic as the end of the world as we know it. Gilbert has helped us open our ears to new sounds and unfamiliar musical territory this year. He has done this in a modest and inviting way. Willing to educate, he has often turned from his Orchestra before he lifts the baton and instructed the audience on the leitmotivs in Schoenberg’s Pelleas and Melisande, for instance. More innovative pieces are often tucked between warhorses.

Gilbert wanted to take a chance, and many Philharmonic regulars ended up coming and enjoying the opera. Even without the usual bracketing only seven people left the opera performance and some of these could have been doctors on call.

Apocalyptic vision is in, but Le Grand Macabre’s seems much more palatable than that of say “The Road,” or “Blindness.” While the end of the world may come in Ligeti’s take, everyone continues to amusingly declaim after they have passed on to heaven or hell. Apocalypse may be now, but it is portrayed with humor, sarcasm, and yes, light. In the Ligeti spirit captured by designer and director Doug Fitch and Gilbert, it’s not so grim.

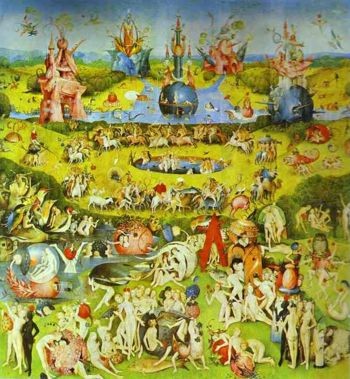

With the original success of Le Grand Macabre Ligeti was invited to go on the popular BBC radio show Desert Island Discs. There you got to choose one book, one impish act, and six pieces. Ligeti chose Alice in Wonderland; his act, to steal Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. The six pieces of music he chose were by Gesualdo, Monteverdi, Mozart, Schubert, Verdi, Brahms, Wolf, and Bartok.

Ligeti revised Le Grand Macabre 20 years after he first wrote it. He undertook the work because he felt the original failed. He hated doing the update. He changed a mostly spoken text to singing, and adjusted roles for some instruments like the contrabassoon because he realized he had written work that was to difficult to perform.

The result is a wonderful opportunity for ensemble performance and Gilbert gathered together a raucous troop from the talent pool in various Lincoln Center constituents and Ligeti regulars. Barbara Hannigan, splendid as Gepopo, the chief of police who wears pink and could give Lady Gaga a few lessons. Her puppet like mechanical movements, often at high speed, did not mask her soprano, stretched to give us both lovely phrases and harsh staccatos.

Melissa Parks as a dominatrix whose range and variety stunned, was somehow able to beat her husband, the astrologer of Breughelland, a timeless land where the opera takes place. She’s not driven crazy when she discovers that he wears a frying pan on his butt to endure her blows. Seeking always for a really well-hung man, she settles on Le Grand Macabre, who kills her with love. This is not however the last we hear from this magnificent mezzo, because characters in the opera appear also in the heavens and hells of their after lives.

Jennifer Black a soprano and Renee Tatum, a mezzo in trousers (a nude male bodysuit) had juicy bel canto-like duets often from a tomb that recalls Aida's. They were probably grateful for their name changes from Clitora and Spermando in the original to Amanda and Amando, but the purpose of the original names to suggest sexual drive remained. Their skimpy grass skirts suggest Eden, or Hawaii--what difference. Sodom and Gomorrah are often mentioned.

Eric Owens, Nekrotzar aka Le Grand Macabre, deployed his beautiful baritone throughout. He wore one of the evocative costumes created by Catherine Zuber. A plumed crown that made him huge as he rode around the stage on Piet the Pot, who plays whatever role is required including Rocinante, a Quixote-type horse.

Piet knows how to survive in Breughelland. Before the opera begins, he has been drinking red wine. He drinks with conductor Gilbert and every other person he can share with. Even before there’s a threat that the world is coming to an end, he has come up with a perfect solution, sung in his compelling tenor no matter what awkward position he finds himself in, including the horse role.

The white and black ministers, about to be pilloried like BP executives in Mad Hatter Hats are Peter Tansits, tenor, and Joshua Bloom, bass. They put a rest to Ligeti’s concern about singers with wonderful voices being able to talk well, one reason Ligeti gave for writing all the song lines in version two. The moving chorus – both physical and in their presentation, appears in the balconies of the hall to throw paper (rotten eggs?) at the prevaricating politicians.

Prince Go-Go arrives wearing a huge soccer ball, ready to be kicked around, his role in the piece. Sung by counter tenor Anthony Roth Costello this part is surely the most beautiful. Sometimes it seems unfair that in contemporary music the composer gives one character lines that sit more easily in our old-fashioned ears. Berg did this in Lulu with Alwa.

Costello has been deservedly showered with awards in his young career, but this has clearly not disturbed his sharp humor and acting ability. His counter tenor makes you wish there were more skirt roles.

Wilbur Pauley, a rich bass, sings in the thankless role as a masochist and astrologist. He comes from a theater and film world, in addition to having formed his own male vocal ensemble, Hudson Shad. He shines.

Rob Besserer crosses over from the world of live animation, where he for instance drops flakes of snow on a bed of red roses, to on stage assistant. He inspires some of the singers to cross over too. They mug the camera, which we see huge on the screen in real time.

Every performer in the ensemble contributed to the zany, moving and arresting production, set in the middle of live action animation created by Doug Fitch and Giants are Small. Other productions of the opera have been placed in Chernobyl or in a huge sculpted woman, every one of whose orifices is used for exits and entrances. Neither enchant. Fitch’s do.

Creating the video projections on stage near the orchestra, Fitch hangs a 26 foot oval screen sprouting sun-like rays. High front and center it is a brilliant take on the score and libretto.

The vibrant opera could not be contained on stage. It spilled over to the aisles where Nekrotzar led a procession of musicians and countrymen waving black spirits. Other musicians were scattered around the hall. Avery Fisher may not have envisaged this, but he would have loved it. Even the balcony lights flashed as part of the show, which erupted everywhere – a triumph over fear.

The play on which the opera is based was first produced in 1934, and its subject is fear and not succumbing to it. About the same time Franklin Roosevelt was saying, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” An apt reminder for our times.

Next year the dynamic duo, Gilbert and Fitch, will bring us Janacek’s Cunning Little Vixen, sure to be a treat.