From The Dishwasher Dialogues

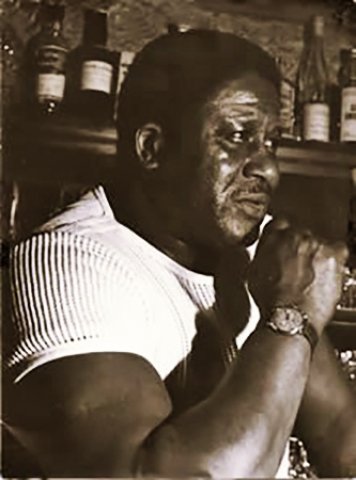

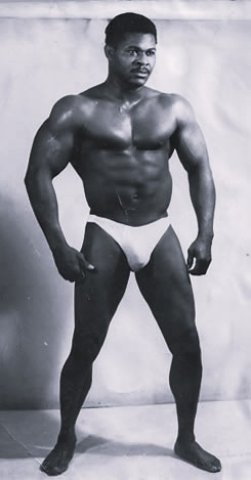

Leroy Haynes, Charles Bukowski and Simone De Beauvoir

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Jun 01, 2025

HE HAD OUR BACKS

Rafael Mahdavi: Looking back nearly half a century, I realize that Leroy lived in his own world. I don’t pretend to understand it now and I wasn’t even aware of it then. I was living fast at the time, taking risks and being self-centered. I had little sense of psychology and suffering.

Despite all Leroy Haynes had lived through he remained kind. I think now that some parts of him had been broken and he had put them back together again, and that made him very strong. He never showed any weakness. He let nobody that I knew get too close to him including us, his staff (at the bistro). Odd as it may sound, his kindness, strength, and solitude were qualities that made me feel that my back was covered.

Greg Light: That is true. Leroy never let us get too close to him on a personal level. We never saw Leroy outside of Chez Haynes, a few times in his apartment. But always to do with work. We never sat down for an extended meal or drink with him, even in the restaurant. He never came to our shows or attended an opening. He rarely talked to us in any depth about his life; bits and pieces escaped in stories or in an emotional response to something. A comment? An event? His demons? It was usually after drinking. Even then, he was guarded. But he was not cold or impersonal. His actions toward us told us that. He certainly knew more about our challenges than we credited him.

Rafael: Leroy’s silent advice was always there, don’t get too comfy, son, life’s tough and it’s not going to get easier. Unlike Manhattan where I had previously lived, Paris, was not menacing. Never did I sense that there were places or quartiers where I shouldn’t venture.

Greg: He knew we would be fine on the street.

Rafael: Only once during my employment at Chez Haynes, soon after I started working as a bartender, did I witness any violence. A drunken client had ordered one more bottle of wine. A waitress brought the bottle over to the table. The man looked at it and shouted, ‘I didn’t order this shit, go get me the right bottle’, and as the waitress turned to fetch a new bottle, the man shoved her from behind, saying allez, vite! The waitress fell to the floor. Leroy must have heard the clatter, and despite his size and weight, he moved fast, helping the waitress up from the floor. The client stood up from his chair to confront Leroy, and Leroy grabbed him by the lapels of his jacket, lifted him off his chair, and threw him out the door and onto the sidewalk.

Greg: Roughhouse Haynes. That was Leroy’s college football name.

Rafael: The clients at the other tables clapped. Leroy hadn’t said a word. He walked back into the kitchen. Oh yes, we felt safe at Chez Haynes.

Greg: He had our backs. Sometimes in unexpected ways. One day I received a phone call from a Radio France producer asking me if I would be interested in reading a French translation of a Charles Bukowski poem for a radio arts program. They were looking for someone who spoke French with a pronounced American accent, and I guess my Canadian accent was close enough. When I asked them how they found me, they said Leroy had given my name to them. Leroy was their first choice. Given Bukowski’s grit laden voice, Leroy would have been fantastic. When he turned it down, they asked him for a recommendation, and he gave them my name. They were offering money. I immediately agreed; speaking in my “under the mountain” French, which is all I had. I am not sure if that was when they began to wonder if they had made a big mistake. The next day I took the metro over to their studios—Maison de la Radio—in the 16th. I was led up to a modern studio. A room with a single stool and microphone in the middle, facing a glass wall behind which were two or three radio technicians. The producer handed me two Bukowski poems translated into French on a few sheets of loose-leaf paper.

Rafael: The French have a fascination with Bukowski, he seems to confirm their deep-seated need to equate creativity and self-destruction.

Greg: I was given a few minutes to read over the poems before I was asked to begin. I think they also gave me copies of the poems in English so that I would know what I was reading. Which was a good idea. I did not immediately understand the French translation. The producer asked me if I was ready, and I nodded. He left and appeared on the other side of the glass window. It all felt like they were in a bit of a hurry. As I read, I began to see expressions of disquiet, then dismay, on the faces of the technicians. Before I had finished the first poem, the producer returned. I asked him if there was a problem and he told me no one could understand a word in my French accent. (Too American? Too much ‘under the mountain’?) We started again and I was a bit better. Eventually he told me that they were only going to use a couple of clips, and they had enough material for their program.

Greg: I was hurried out by an assistant who told me they were taping an interview with Simone de Beauvoir for the same program. Soon after, I think it was the same evening, the program was aired with a few moments of Bukowski, unspeakably massacred by me (sorry Charles), followed by the marvelous intelligence of de Beauvoir (thank you Simone).

Rafael: Interesting. I knew little about Simone then, only that she had written a seminal book about women and for the women’s movement. Later I read quite a lot about her and her behavior during WWII and the German occupation of Paris. Not nice. So, my view of her life and philosophy is jaundiced. Sorry about this.

Greg: Why sorry? All our lives are ‘jaundiced’. There are ‘not nice’ episodes about us in these dialogues. Some, between the lines, conveniently omitted or unremembered. But, nevertheless, we are responsible for them. We were lucky that the demands on our character during our time in Paris were not as intense as they would have been for those living during The Occupation. How would we have fared? I suspect Simone did not cover as many backs as she might have. The stakes were nowhere near the same. But Leroy did have our backs. At least from time to time. He even helped me get film work.

Rafael: Leroy had worked in a number of movies, and in retrospect I think if we had asked him for help, he would have helped us. I was too reticent and, in an odd way, ashamed. He was already helping us so much by keeping us on the payroll.

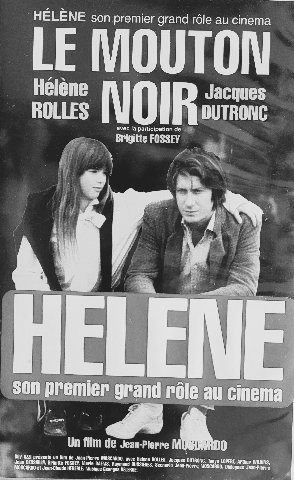

Greg: I was more or less immune to shame back then. Especially when there were a few francs going and nothing to lose. You were always more circumspect. Serious. You had something to lose, a rising reputation— solo shows, even then, in Paris, New York, London. I never directly asked Leroy for help, but I think he liked to help where he could. It was part of who he was. I do not fully recall the details of how the film job came along. I think Leroy gave me a name and number to contact. The producers were looking for someone to write the English language dialogue for a French feature film called Mouton Noir. The French script was complete and the actors already cast: Jacques Dutronc, Brigitte Fossey and a young Hélène Rollès. Some of the film centered around an American restaurant in Paris which is more than likely why Leroy was contacted. I was asked to write some English dialogue for those scenes. At some point a few days in, the producers had this idea of filming a full English version alongside the French version to tap a potential American audience. I was asked to help with the English version. For a few days, it looked like this could be a big break. But Dutronc was not happy with the idea, and once he started speaking English, it was clear why. His fluency in English rivaled my French version of Bukowski. They immediately scrapped the idea. But I did get a small acting gig: essentially playing myself, an American guy in an American restaurant. Finally, my accent and my everyday wardrobe came in handy.

I was given a half dozen lines in the film, even a close-up. I remember going to a cinema on the Champs-Élysées to see a film and my close-up suddenly popped up in a ‘coming attraction’ trailer. Mouton Noir was eventually released to poor reviews. There were some excellent actors, but the film was not. Despite having worked on the set for ten days, my acting and writing contributions in the American Café were never credited. Illegal immigrants got cash and nothing else. Nevertheless, the hard evidence of my work, and me looking like I did back then, is there in moving images for all who care to see. So far just my wife and children. But more importantly, the film shows Paris as it looked in the 70s when we were living it. And that is worth the price of a ticket.

NEXT WEEK: THE IDEA