Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe

Art Under Fascism Explored at Guggenheim Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 02, 2014

The most in depth exhibition of the movement ever seen in the U.S. Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe is on view in New York at the Guggenheim Museum through September 1.

The fascinating and controversial survey of art that embraced Fascism and celebrated war includes 360 works, by nearly 80 artists, architects, designers, photographers and writers that have come from some 50 lenders. Half of the works which are loaned by Italian museums and archives have rarely if ever traveled.

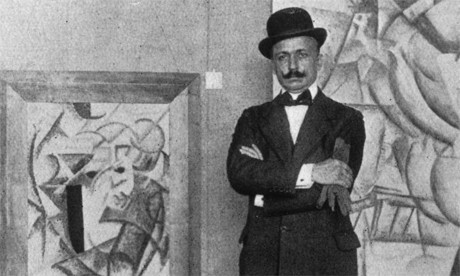

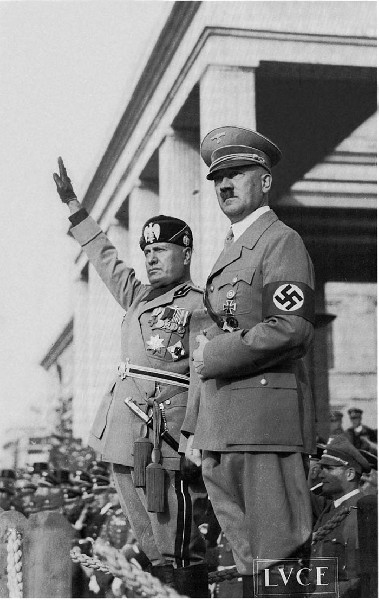

Most Americans form their impressions of Futurism based on superb examples in the Museum of Modern Art from the classic period around World War I. This is a rare opportunity to see works by a second generation, by then intimately embracing Benito Mussolini, through the defeat of Italy and the death of the movement’s leader the poet and polemicist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1944.

“We want to glorify war — the only cure for the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman” Marinetti famously stated.

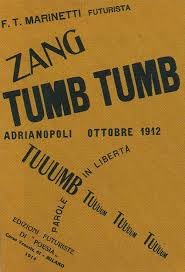

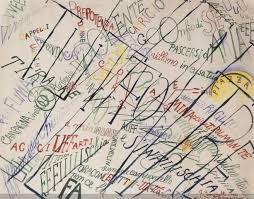

Zang-tumb-tumb-zang-zang-tuuumb tatatatatatatata his unique and revolutionary poetry declared. It emulated the sounds of battle. He had been a war correspondent on the Ottoman battlefront two years before the First World War.

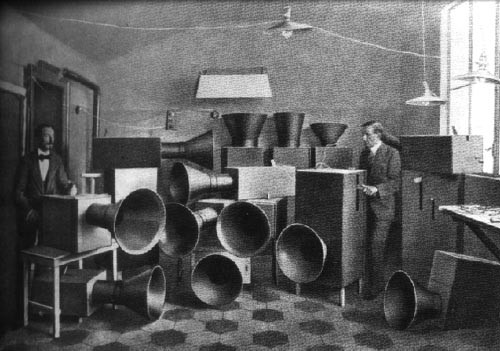

The aesthetic strategies of Marinetti and his peers, particularly Luigi Russolo’s pursuit of noise music and its apparatus, resembled the pacifist Dada artists escaping war in the infamous events of the Café Voltaire in Zurich. Not far away Lenin languished in exile until smuggled back into Russia by Germans intent on fomenting the revolution.

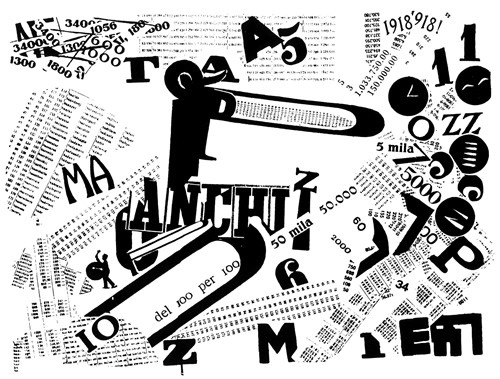

On many levels the Futurist movement has been an enigma for art historians. This landmark exhibition embracing literature, the fine arts, graphic design, fashion, photography, theatre and architecture broadens the reach of critical analysis and dialogue.

While a fascist ally of Adolph Hitler and Hirohito oddly Mussolini was more sophisticated and tolerant of artists. Perhaps this was because they shared his radical political and military strategies. The greatest painter and sculptor of the movement, Umberto Boccioni, joined the army. He was killed while training when thrown from his horse.

This complex and brilliant exhibition contrasts sharply with the small but insightful sketch of the Degenerate Art banned by Hitler now on view at New York’s Neue Galerie. A visit to the National Arts Club at Gramercy Park surveys 35 works of the Russian avant-garde that overlaps these other exhibitions.

If the art of Germany, Italy and the nascent Soviet Union reflected social and political upheaval, that was not the case in Paris. Artists in Italy and Russia in particular drew their inspiration and formal structure from the developments of Cubism.

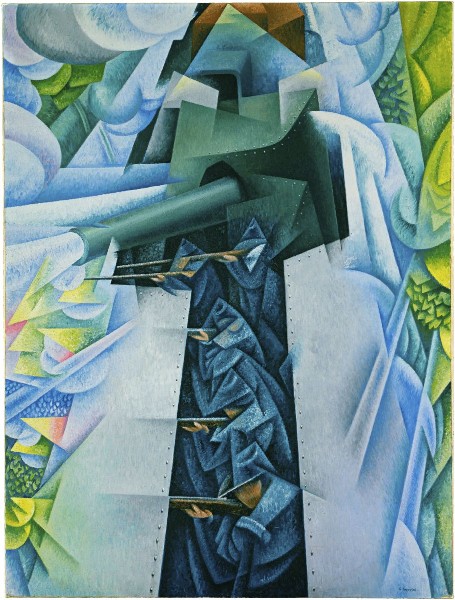

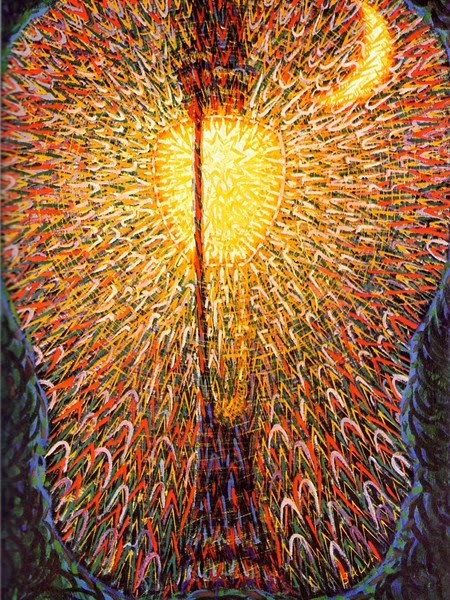

A thumbnail analysis of Futurist art is that it follows Cubism with the addition of force vectors, energy and celebration of the machine. In their xenophobic jingoism Marinetti and his gang embraced all aspects of modernism and the technologies of war that would restore Italy to the glory which had lapsed since the decline of the Roman Empire.

Perhaps the greatest paradigm is Boccioni’s masterpiece “The City Rises” in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Another key work is Carlo Carra’s “The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli.” The connection to war is literal in the abstracted figures of Gino Severini’s “The Armored Train” which depicts Italian soldiers wearing the unique hats of Alpine troops.

The masterpiece of motion in sculpture is Boccioni’s brilliant “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.” The paintings of Giacomo Balla generally convey the Futurist embrace of a bullet, airplane or locomotive as “More beautiful than the Mona Lisa.”

Of course, in the long run, La Giaconda wins hands down. Unlike the Taliban in Afghanistan destroying ancient Buddhist art the Futurists never made good on their threats to blow up museums and libraries. It was more political theatre than an actual threat. The dilemma of Italian artists is constantly to be surrounded and in competition with a nation which is a virtual museum of centuries of culture.

For Americans, in our crass young nation, there is no such problem. While Thomas Cole traveled to Italy to paint its ruins his fellow Hudson River artist, Asher B. Durand, stayed at home in pursuit of “That Wilder Image.” Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon were the American equivalent to Europe’s monuments.

Marinetti in addition to a mandate to destroy the legacy of Italian culture also attacked its matriarchal heart and soul with a misogynistic statement about “contempt for women.”

It’s hard to get away with that in a nation ruled by Mama and celebrating amore. His chauvinism has been red meat for feminists to attack Futurism.

How then to explain one of the greatest surprises of the exhibition a series of large, decorative, nationalistic 1930s murals from a post office in Palermo by Marinetti’s wife Benedetta Cappa. Her work has captivated visitors to the exhibition with their scale, energy and fresh colors.

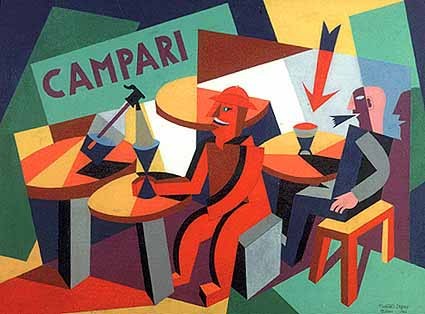

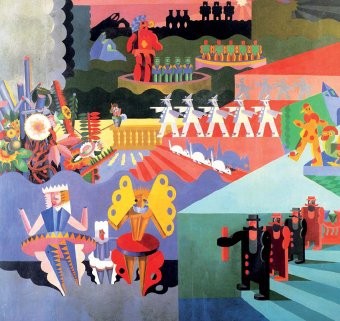

There are many discoveries in this survey particularly fashion with colorful vests and a room of furniture that includes ceramics by several artists. There are theater costumes and set designs, toys, animation, and a dining room ensemble. These artists notably include Gerardo Dottori and Enrico Prampolini. Graphic designs, particularly posters for Campari by Fortunato Depero, were a revelation. Other works by Depero include the painting “Stormy Patriot Marinetti: Psychological Portrait” and a cement-coated kiosk designed for a publishing house’s promotion at a book fair.

Other than a single interesting example with an elaborate set and stilted action the Futurists did not venture far into film. Similarly there is a smattering of photography. The images by Anton Giulio Bragaglia are particularly interesting as they convey the notion of blurred movement. They may be considered as precursors of the strobe studies of Harold Edgerton.

In this sweeping overview there is but a tantalizing thumbnail of Italian modernist architecture. Hitler had reactionary taste. The seminal Bauhaus was closed and its primary artists and architects, including Lazlo Moholy Nagy, Mies and Walter Gropius, fled to America.

As a failed artist and amateur architect Hitler collaborated with the fascinating but doltish Albert Speer to develop a style of monumental, totalitarian, neo classicism with little regard for proportion and scale.

In Italy, under the aesthetically more tolerant Mussolini, the International style prevailed. Other than that terrible error The Altare della Patria (Altar of the Fatherland) also known as the Monumento Nazionale a Vittorio Emanuele II (National Monument to Victor Emmanuel II) which was dedicated in 1925. Ironically, like the Futurists, Il Duce was willing to destroy a large swath of ancient Rome to create a vulgar monstrosity. The “Wedding Cake,” as the Italians call it, continues to be a blight and eye sore in the Eternal City. It could have been designed by the tag team of Hitler and Speer.

The second generation of Futurism prevailing until 1944 evokes a familiar paradox of the avant-garde. The earliest works have the raw energy and ambivalence of experimentation. There is what the late Robert Hughes described as “The Shock of the New.” Initial works are fueled by experimentation and its process of trial and error.

Once established, however, its radical aspects become fixed and formulaic. Only the greatest artists are willing to risk moving on to new challenges. This is particularly true once artists begin to receive critical and financial success. The Marxist critic John Berger described this process in “The Success and Failure of Picasso.” He discussed the later Picasso, by then isolated from other artists, as entering the studio each day to clone himself by making Picassos.

Those who simply followed his innovations were described by Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, as Salon Cubists.

First come the path finders and trail blazers. The next wave represents the settlers. Eventually that pioneering spirit devolves into the artistic equivalent of malls and Walmart.

This exhibition has attractive and kitschy examples of that phenomenon. There is a whole genre of aerial views of planes and vortexing landscapes. Before the Parachute Opens (Prima che si apra il paracadute), by Tullio Crali, 1939 has crowd pleasing appeal. I wanted to laugh out loud while viewing paintings that abstracted and celebrated Mussolini. It was ludicrous if not terrifying.

Much is being made of The Monuments Men who rescued art stolen by the Nazis. A lesser known sidebar is that Nazi art was confiscated with much of it preserved in state of the art facilities by orders of General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

It is feared that displaying it will inspire neo fascism. Which is why the Fuhrer’s bunker, too formidable to destroy, was filled with cement and fenced off. It was feared that it would become a shrine to The Third Reich.

Perhaps that is an aspect of why Futurism, with its embarrassing political concepts and allegiance to a failed cause, continues to be denigrated. It is difficult to navigate through this entirely as an art exhibition.

The Guggenheim installation, however, encourages that formalist, art historical approach. We are encouraged to encounter this as an immersion in an art movement.

But Futurism and its embrace of Fascism resulted in consequences.

Yet again we are confronted with great art for a bad cause. Like the films of Leni Riefenstahl, masterpieces of their genre, how do we approach provocative works of art which played a role in the loss of millions of lives