Fugard Theatre's A Human Being Died that Night

Truth and Reconciliation at the BAM Fisher

By: Susan Hall - Jun 03, 2015

The Fishman Theatre at BAM is filled with a smoky fog wafting from the spotlights. As if to bring clarity to a tortured history, a young black women, Pulma, steps forward to speak.

She begins and then stops, reporting that she must change her glasses. She does. Introducing us to what was at the time a revolutionary approach to perpetrators of atrocity, she asks: What should be our attitude toward the people who have committed these atrocities? Do we fear finding them as human as we are? In effect, do we need to look at them (and ourselves) differently?

When Eugene de Kock, who the press labeled “Prime Evil,” came before a hearing of the South African Truth and Reconcilaition Committee, he asked to meet the wives of three policemen he had killed. He wanted to apologize to them.

Pulma is intrigued by the request and arranges to interview him. In the stunning play Nicholas Wright forged from this interview, A Human Being Died that Night, we are taken into a simple cell in a receiving area in prison. Paul Wills designed the set where violence lurks at the beginning and a comfortability inhabits the conclusion.

This caged area is larger than Mandela’s cell, whose miniature size Matt Damon dramatized in Invictus by spreading his arms out and touching both walls. At the action's start, director Jonathan Munby lets violence hang in the air. Will the prisoner, shackled only to a chair, leap at the interviewer?

Like Mandela’s cell, the area opens out emotionally as the interview progresses. Mandela prepared for the presidency in his cell. We do not know what deKock's future holds. He does tell us that he would like to be reunited with his family and move to Libya.

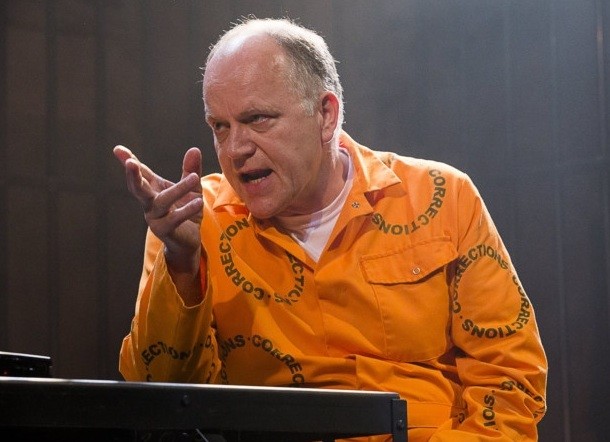

de Kock, brilliantly rendered by Matthew Marsh, describes the atrocities he commited with more and more feeling. He finally collapses into the story of a man who flew through a window and faced him directly before deKock killed him.

The noble Noma Dumezweni as Pulma does not reveal her own story to deKock, but we learn it as she tells us of her own rape and a sister who has died of AIDS, transmitted by her husband.

No one is innocent in this world.

South Africa was one of the first countries to adopt the idea of catharsis and healing as it began to recover and move on from the evil of apartheid. Since the formation of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1912, South Africa had been at Civil War. Everyone who looked deeply at the country over the years thought South Africa would end up drowning in a bath of blood.

Through the miraculous of the alliance of F. W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela it did not.

Catharsis is noted by both Aristotle and Plato as a purpose of tragedy. A recovering South Africa wanted to pick a path toward truth and healing.

In some ways this play's audience bears witness to the dialogue that took place between deKlerk, State President of South Africa, and his prisoner, Nelson Mandela, before Mandela exited jail to lead the nation. (Matthew Marsh looks a bit like deKlerk.)

We were, of course, not privy to that conversation, but the feelings of the two men, black and white, native African and Dutch farmer who loved his country too, are similar.

This is not to say that the characters of Pulma and deKock are not individual and marvelously specific. Indeed they are. And so too are their feelings. Yet both characters have distanced themselves emotionally in order to understand what had happened. Both close in on their feelings as the details of their stories pile up.

Playwright Wright, working from Pulma’s book, lifts us into the hearts and minds of oppressor and oppressed. Pulma has liberated herself by leaving South Africa to study at Harvard. DeKock wants to free himself from his past, not by forgetting, but by telling the truth. In the play’s final moments, Pulma decides that she may stay in South Africa and deKock hopes that he will be freed, even if he has to leave his beloved country.

At the conclusion both characters admit that they did not know what the other was thinking. What is unsaid but clear is that they each have understood the other's feeling.

From the story of deKock and Pulma, other stories will emerge and hopefully a new national history. The future of democracy in troubled countries may well depend on this kind of catharsis. But the pleasure of this production is not weighted down by such general thoughts. Remarkable hardly describes the evening's drama.

Note: In January, 2015, deKock was given parole from his double life, plus 211 year sentence.