First Nations at Art Gallery of Ontario

A Third of the Museum’s Gallery Space

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 03, 2019

Before an appointment as director of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts Matthew Teitelbaum was director of the Art Gallery of Ontario in his native Toronto. During a recent interview I asked about his approach to First Nations artists at AGO.

“I have had a personal interest and a professional interest in the art of First Nations people," Teitelbaum answered. “I felt for a long time that their history was the history of Canadian art. Under my watch we acquired the first, historical, First Nations art ever. The museum hadn’t collected that material. We integrated First Nations art into displays of Canadian art on a consistent basis. I was very proud and pleased when we hired Gerald McMaster as the head of the Canadian Department. It was the first time a First Nations leader had been appointed to lead a department other than First Nations. The notion of putting his voice in the middle of development of history was very important to me.”

He discussed similar strategies for inclusion at the MFA. Recently, however, there was national media coverage of racism experienced by an African American school group visiting the museum. He issued an apology and initiated measures to address a broad spectrum of changes.

The MFA is not the only major American museum caught in the cross hairs of institutional racism. In addition to issues of welcoming and including minority communities there has been pervasive neglect and mishandling of Native American art, history and culture.

There was controversy surrounding the Jimmie Durham retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The artist, who has resided in Europe for many years, claims Cherokee heritage but is not enrolled. There is outrage that the only retrospective for a Native American artist at a major American museum presented an individual whose heritage is questionable.

The Walker Art Center displayed “Scaffold” by the Caucasian artist Sam Durant. Sited on Dakota Land it commemorated the hanging of 38 Dakota Indian men in Minnesota after the United States-Dakota war in 1862. As the result of protests it was taken down and given a ritual burial.

The museum has launched an open call directed at Native American artists for a public art project to be exhibited at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden or on the Walker campus by 2020. The open call for the new commission is written in Dakota and English. Museum staff will work with an eight-person committee, including Native American artists and curators, to shortlist three submissions from the pool of applicants.

The New York Times reported that the museum’s executive director Olga Viso “was not always open to criticism or warnings — including over ‘Scaffold.’ ” She is no longer with the museum.

Kathleen Ash Milby, associate curator for the National Museum of the American Indian, feels that “Canada is way ahead when it comes to Indigenous topics.” She is concerned that museums might avoid showing Native American artists after the Durham controversy, thinking “I don’t want to step into something I don’t know enough about. This is too fraught.”

There are only a few American museums with significant Native American programs and curators. The short list includes the Denver Museum, Heard Museum, Portland Art Museum, Seattle Art Museum, National Museum of the American Indian, The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, and Peabody Essex Museum.

Some museums are initiating more diverse strategies. There are more seats at the table, including artists and community leaders, when creating exhibitions and building collections.

During a recent Canadian road trip we visited AGO to get a better sense of what that entails. First Nations galleries comprise a third of the museum’s exhibition space. Other than a single painting by the Native American artist, Fritz Scholder, none of the work was familiar to me.

The galleries included work by deceased as well as contemporary artists. Particularly among the older artists there were abstract works reflective of mainstream movements. Some, but not all of the work, is based on First Nations traditions and social/ political concerns. There are wall labels and signage in English, French, and Anishinaabe.

It evoked the conundrum of identity in the work. What comprises First Nations or Native American art? Is it defined by the ethnicity of the artist or the subject matter? When the work is based on rituals and tradition who owns the rights to what is shown? Can the work on view offend indigenous visitors? What boundaries and limitations prevail for reviewing or discussing the work? How should critics and curators present tribal traditions and culture? Why have First Nations and Native American art been marginalized?

To help understand the issues let’s run the numbers.

As of the 2016 census, indigenous peoples in Canada totaled 1,673,785 people, or 4.9% of the national population (36 million), with 977,230 First Nations people, 587,545 Métis (a person of mixed indigenous and Euro-American ancestry) and 65,025 Inuit. 7.7% of the population under the age of 14 are of indigenous descent. There are over 600 recognized First Nations governments with distinctive cultures, languages, art, and music.

The 2010 Census stated that the U.S. population on April 1, 2010, was 308.7 million. Out of the total U.S. population, 2.9 million people, or 0.9 percent, reported Native American or Alaska Native alone. In addition, 2.3 million people, or another 0.7 percent, reported Native American or Alaska Native in combination with one or more other races. Together, these two groups totaled 5.2 million people. Thus, 1.7 percent of all people in the United States identified as Native American or Alaska Native, either alone or in combination with one or more other races.

Compared to other minorities there is less leverage for Native Americans across a spectrum of social, political, economic and cultural issues. That is slowly changing with new projects and different approaches.

“Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” which opened on June 2 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, displays a thousand years of art. It entailed a different approach. The curators Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves, formed an all-female advisory panel of 21 Native American artists and experts from across the United States and Canada.

As makers of artifacts the work of women has been marginalized as arts and crafts. This project moves beyond sexism and colonialism. Museums have inappropriately displayed funerary objects considered sacred. This includes ceramic objects created by the Mimbres women of New Mexico. The masks were placed over faces of the deceased. Examples are displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

An exhibition of Mimbres pottery planned for the Art Institute of Chicago was put on hold indefinitely. Curators were called out for not engaging community leaders. For the MIA exhibition curators searched for an ancient, non funerary Mimbres pot. One from Utah, circa 1000, is included in the exhibition.

There were similar issues regarding a quill-decorated, Cheyenne, 1800s warrior’s shirt. When consulted, the Cheyenne community declined permission to display the object. Instead they provided a beaded pipe bag made by the Cheyenne/Kiowa artist Heather Levi.

This is a different way of proceeding. In the past curators routinely assembled consultants for a meeting. They checked off the N.E.A. grant-writing stipulation for a diversity of voices. Then curators did whatever they wanted. Community members were asked to provide authority to a show but had no authority over it. A better approach entails listening and responding to Native American communities.

That’s the bottom line of diversity and signifies tough lessons for Teitelbaum’s MFA and other cultural institutions.

Some years ago, I first experienced the work of Jeffrey Gibson at Boston’s Samson Gallery of Camilo Alvarez. The artist has been widely shown since then. Supported by The Mississippi Band Choctaw community he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Royal College of Art in London. Gibson, however, is ambivalent about being presented as a Native American artist rather than just a contemporary artist.

The year long exhibition “Jeffrey Gibson: Like a Hammer” has been presented at the Denver Art Museum. While invited to exhibit as a Native American artist he finds that problematic. “People believe that by supporting me, they are supporting a Native American art world, but I am not sure that’s true,” he told a reporter “I’m not representative.”

Similar views have been expressed by the Cherokee artist Kay WalkingStick (born in 1935) one of the best know and widely respected artists of her generation. A national tour of 60 works, curated by Ash Milby, ended at the Montclair Museum of Art.

“My goal was to open up the mainstream to Native American art,” she stated “And it has absolutely gotten better.” Like Gibson and others she emphasized that it is important to progress beyond the expectation that “Indian artists made art about being Indian.”

Christina Burke, a curator for the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma and its “Hearts of Our People” describes how things have changed. “The process was totally different than any other exhibition I’ve worked on in 30 years,” she observed. “I’m an anthropologist, and there’s a long history of an imbalance of power — anthropologists are sometimes known as culture vultures who come into communities and collect objects and stories and songs and leave and never go back.”

During a recent Canadian tour from Montreal to Toronto we visited major museums. There were different approaches to presenting First Nations artists.

A one man show by Kent Monkman at the McCord Museum in Montreal was truly astonishing. He is a major player of the global artworld. To a lesser extent the work of Inuit artist, Shuvinai Ashoona, has reached an international audience. She was included in a three artist installation at The Power Plant in Toronto.

At the National Gallery in Ottowa there was an apples and oranges juxtaposition of Inuit and modernist Canadian art. It was disorienting, for example, to view a large abstract painting through a vitrine of Inuit sculptures.

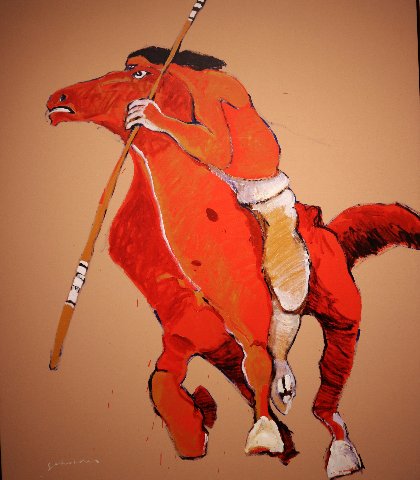

The more successful approach was the total immersion of First Nations galleries at the AGO. The work evoked a range of impact from apathy to fascination. With apologies to Gibson and WalkingStick the strongest responses were to “Indian artists (that) made art about being Indian.”

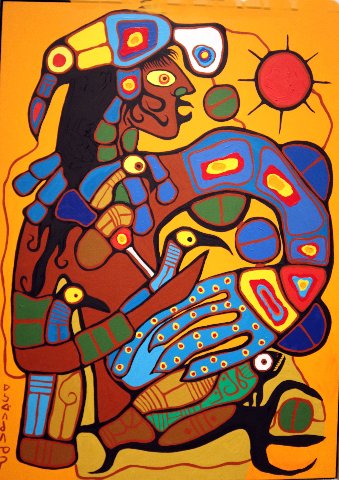

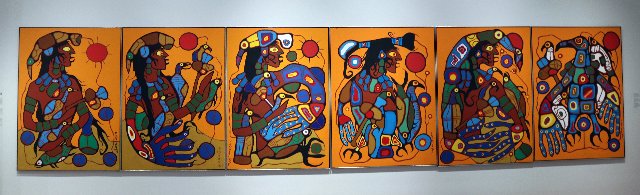

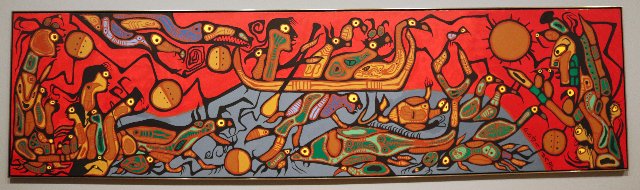

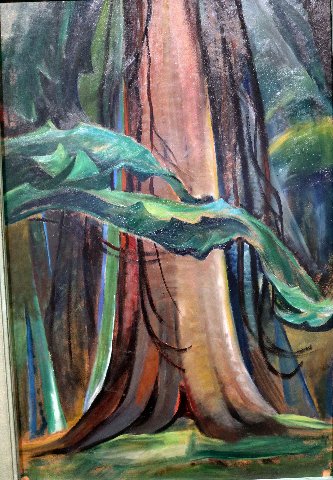

When that works the synergy is sublime. The large panels and panoramas of Nerval Morriseau (1931-2007) were ravishingly revelatory. With strong black outlines filled in with high chroma color he evoked shamanistic traditions with a series of magical thunderbirds. Absorbing them as galvanic design surely I missed the embedded symbolism. They functioned primarily as impactful paintings. Individuals sharing his culture and traditions view them differently. He is credited with founding the Woodlands School of Canadian Art and was a member of the Indian Group of Seven. It is said that he influenced younger artists.

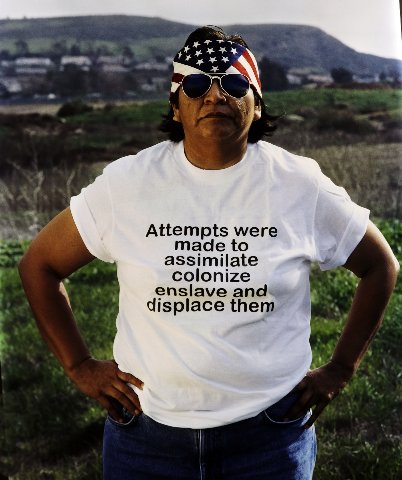

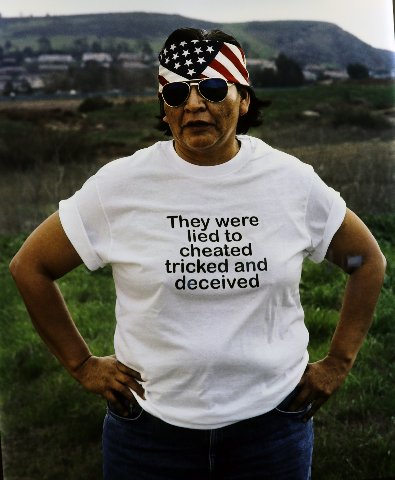

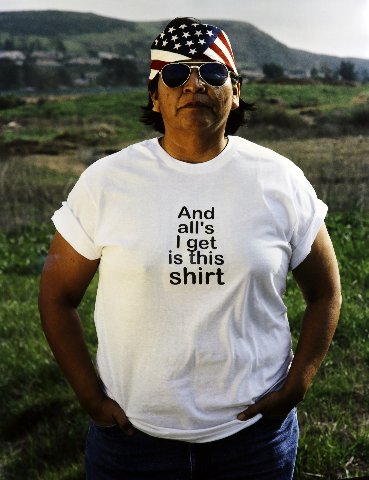

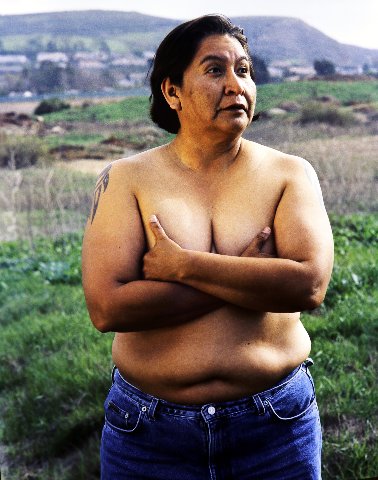

Paricularly thought provoking was “The Shirt” (2003) with framed images of the artist Shelly Niro (born 1954). Each photographed segment reveals the artist spelling out horrors inflicted on her people. The piece was conceptually simple but packs a wallop.

There are televisions set side-by-side on the floor in “Seven Sisters” by Mike MacDonald (1941-2006). The videos present a panorama of mountains in British Columbia.

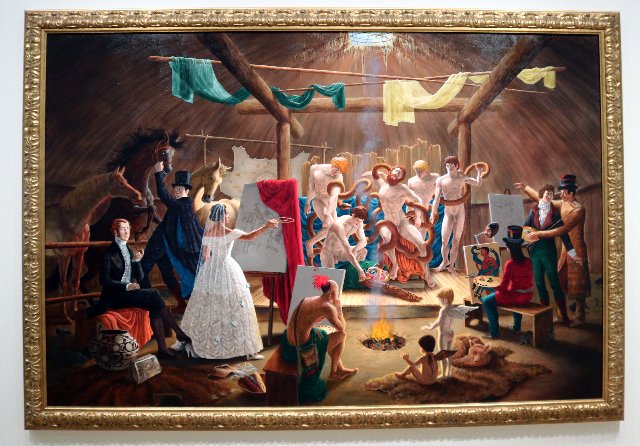

Included in the permanent collection is “The Academy” (2008) by Kent Monkman (born 1965). It depicts quotations from classical art including a grouping of the Hellenistic sculpture “Laocoon and His Sons” ensnared by snakes. Like a plaster cast in a drawing class the sculpture is circled by artists at easels hence “The Academy.” There are art about art quotes. One of these is the famous detail of a Noble Savage as witness in “The Death of General Wolf” by Benjamin West.

Two cutouts of wolves set on the floor by John McEwen (born 1945) comprise “The Distinctive Line Between One Subject and Another.” Underscoring its subject “Angel” (1979-80) by Robert Nelson Markle (1936-1990) was hung well above eye level. It’s a whimsical, winged squiggle accented with neon.

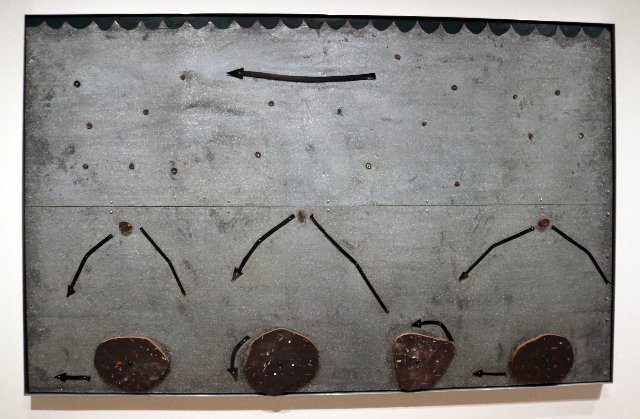

A conceptual piece “Don’t Breathe Don’t Drink” (2016) by Ruth Cuthand (born 1954) focuses on environmental issues. A table set with “polluted” vessels of water relate to 94 First Nations reserves with water advisories and toxic housing. She uses beadwork to represent bacteria and disease.

The artist and curator Robert Houle (born 1947) conflates text and abstract painting in “Premises for Self Rule-Constitutional Act” (1982, 1994).

While there is exciting progress much remains to be done. With increased support and eduction there is great potential for emerging artists and curators. Between now and then major American museums need to rethink their apathy and initiate progressive programming. This process should involve critics and audiences.

Undertaking a national soul searching and healing process is all the more challenging and necessary under the current political enviornment. Reporters have asked directly "Mr. President are you a racist?" Building walls, incarcerating immigrants and seizing their children perpetuates America's horrific traditions of colonialism and genocide. The arts represent a vital recourse for resetting the direction of our nation's moral compass.