Searching Yet Again for Aviator Amelia Earhart

America’s Most Famous Missing Person

By: Edward Rubin - Jun 04, 2014

The Amelia Earhart, Image and Icon exhibition at the International Center for Photography is a small, tightly focused exhibition that not only entertains but sheds much light on the early days of photographic image making by digging deep into the photo history of both its subject, Amelia Earhart, and the medium of photography that helped bring her to fame.

Co-curated by Kristin Lubben and Erin Barnett, Image and Icon — consisting of 50 prints, 8 newspapers, 13 magazines and a continuously running newsreel — sprung from an idea that Earhart biographer Susan Butler, and the aviatrix’s cousin Ann L. Morse had for an illustrated book of photographs that documented the famous pilots life. “Though the book proposal had much merit,” Lubben said, “after a number of discussions we all agreed that everybody involved would be served a lot better by an exhibition that examines such issues as the nature of photography, the rise of photojournalism, and the power of the photograph to create celebrity.”

True to Lubben’s statement, Amelia Earhart (1897-1937), the first woman to cross the Atlantic in 1928, and the first to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1932 — still an enduring legend seventy years after her disappearance — is the perfect subject with which to examine the role that photojournalists played in establishing Earhart’s fame.

As fate would have it, the aviatrix, whose youth and beauty were a photographer’s dream, was born on the cusp between the gentle demise of 19th century woman and traumatic birth of her 20th century counterpart. As a fledgling Boston based social worker, Earhart was modest, soft-spoken and caring and considerate of others. As a stunt pilot, the adventuresome Earhart — held up as an example of the so-called “New Woman” — was frightfully daring; a ‘thoroughly modern Millie’ out to prove that “woman can do most things that men can do.” This was the image the public was offered. This was the image that they bought.

While Earhart, throughout her short life, worked tirelessly to support her flying, to go from obscurity to a household word, she relied heavily on the considerable help of George Putnam, first her manager, later her husband. Putnam, whose family owned G. P. Putnam, published Lindbergh’s best selling book, We, and later on Earhart’s own books, had strong connections at The New York Times, Paramount Studio and other media outlets. Working in tandem with Earhart, the press savvy Putnam, a media genius, took every opportunity to push and polish the aviatrix’s reputation.

Every outing was to be a photo-op. Earhart herself was no slack. Having worked in a photography studio in her mid-twenties and later briefly operated her own photography business with a friend she knew exactly how to face a camera. She also knew what to hide and what to show. Judging from the photographs in the exhibition, it appears that she was not at all thrilled with the Alfred E. Neuman space between her two front teeth. In almost all of her smiling portraits, if she isn’t turning her head to offer a side view, she is seen, somewhat calculatingly, lips together, mouth closed. In one wonderful photo taken from her book 20 Hrs. 40 Minutes, obviously feeling giddy, she laughingly sticks out her tongue, exposing the gap for the world to see.

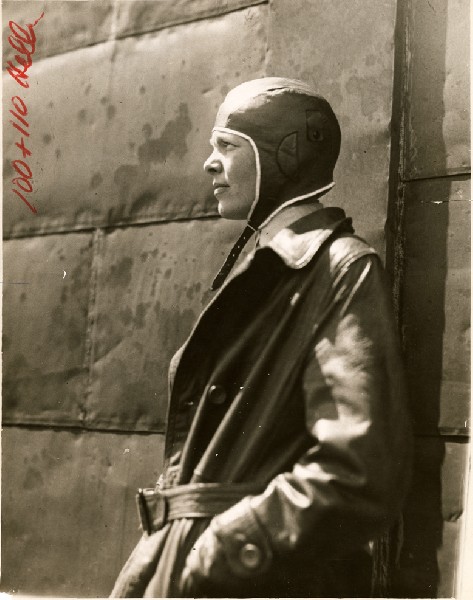

Earhart’s most popular and widely disseminated image, the one that still sticks out in our memory today — the aviatrix in a leather jacket, lace-up boots and a flying helmet looking straight into the camera — was a stylistic template established by other female flyers at the time. Still, as Lubben points out in the exhibition’s wonderfully illustrated catalogue, both the pose and her dress was not the construction of a publicist but an authentic version of Earhart’s, albeit refined, prefame self-presentation. Interesting enough, her masculine image, considered standard fare today, in the context of 1930s gender roles was somewhat threatening to the public.

As such, photographs of Earhart required special handling whether within the photo image itself or throughout the framing device of layout, picture selection, captioning. To soften her image Earhart when wearing her flight suit, would often place a feminine scarf around her neck and occasionally sport a string of pearls. Magazines and newspapers using photo layout to feminize the aviatrix, tended to place a picture of the leather clad aviator next to one of her wearing a dress. The intent was to remind the reader that underneath it all Earhart’s femininity is unassailable.

While portraits of a the smiling Amelia in her flight suit, standing proud and self-assured, are peppered throughout the exhibition — a similar portrait is featured on the cover of the exhibition’s catalogue — photographs of Earhart dressed to the nines (she was voted one of the ten best-dressed women in 1935 by the Fashion Designers of America) are also on view. Here she is seen wearing elegantly tailored skirts and dresses on public occasions. How else to lunch with the President, meet Mussolini and have an audience with the Pope.

She preferred to wear pants in ever day life and it seems the photographers and public, fascinated by the dare-devil pilot, liked her best in her flying uniform and as close to her plane as possible. Sprinkled throughout the exhibition are photographs of the aviatrix at the controls in her cockpit, holding her propeller, or sitting like a bathing beauty on the nose of her plane. These stock images, refined and repeated in photographs, and widely reproduced in the press for nearly a decade, contributed, as Lubben writes, “to the vision, of what women could do and look like.”

In many ways, the steps necessary in making of Amelia Earhart into a household name parallels those of the early Hollywood movie star system. When not racking up her record breaking flying triumphs — Earhart’s version of a hit movie — the aviatrix spent every waking hour, attending carefully staged promotional events, endorsing products, posing with Hollywood movie stars and giving countless lectures across the country, all of which resulted photographs that immediately found their way into the press. Although Earhart did sit for Edward Sreichen, Vanity Fair’s top fashion and celebrity photographer in 1931 and Anton Bruel photographed her for Vogue in 1933, most of the pictures of Earhart, both in real life and in this exhibition, were taken by little-known staff photographers at newspapers or wire services at public events.

Another exception to the ‘nameless photographer’ rule was her photo session, arranged by her husband on the eve of her first flight across the Atlantic, with Paramount Studio photographer Jack Coolidge. Here, under the theme “Remembering Lindberg,” Coolidge photographed Earhart in her signature outfit, leather jacket, laced up boots and helmet. The photographs widely circulated with captions that pointed out the similarities between the two flyers, much to the dismay of Earhart, saddled her with the nickname “Lady Lindy.” Coolidge was to claim that “it wasn’t so much that the resemblance was there as that you could make it seem to be there by camera angles.” While many of the images on view come from ICP’s, LIFE magazine collection, nearly half of images tracked down by Co-Curator Erin Barnett, over the course of the two and a half years it took to mount the exhibition, are on loan from The New York Times and the Condé Nast photo archives.

With the growth of the airline industry, the rise of the male career pilot and the fickleness of the public, Earhart was pushed from front page to back page news. In order to rekindle her popularity, the ever daring aviatrix, surely in cahoots with her manager husband, planned to fly around the world, a feat yet to be accomplished by man or woman. But best laid plans oft go astray and Earhart and Fred Noonan, her chief navigator, never to be heard from again, disappeared over the Pacific Ocean on July 2, 1937. A rescue attempt commenced immediately, the most expensive air and search in naval history. On July 19, after spending $4 million and scouring 250,000 square miles of ocean, the United State government reluctantly called of the search.

The public mourned, recycled photographs of the thirty-nine year old Earhart appeared on the front page of every newspaper in the country, and magazine articles proliferated. As to be expected the memory of Earhart was quickly laid to rest. With the advent of World War 11, conspiracy theories claiming that Earhart was a U.S. spy and a Japan prisoner of war brought her to the public’s attention again.

In the 1970’s, after thirty years of dormancy, a photograph of trench-coated, gap-toothed, tousled hair Earhart — now co-opted by the feminist movement — was featured on the cover of Ms. Magazine. In the 90s, after a long sleep, photographs of Earhart, now positioned as a trailblazer, and one who thinks out of the box, was resurrected once again, this time to sell products for Gap and Apple.

Today, Earhart is revered less for what she did than for what she stands for. Correspondingly, her iconic photographic image today is much more singular than it was in her time, when a public was very familiar with her narrative and could identify and was interested in images of her range of activities and guises. She has become an increasingly abstract symbol — of the thrill and danger of adventure, of the possibilities for women, and of the courage to break with the past and conventional expectations. In this process, her image has become consolidated, and only those photos that convey those ideals stand in for her.

A dramatic and conspiracy theory-plagued disappearance (rather than death) has kept her narrative open-ended, and aided in the afterlife of photographs of Earhart.” Judging from this exhibition, there is a lot more mileage left in the old gal. Just you wait, she is sure to be trotted out again and again. As for the decades old photographs, they will continue to be beautiful and inspiring, and Amelia Earhart will remain, forever thirty-nine.

This piece published here for the first time was a review of Amelia Earhart Image and Icon at International Center for Photography from May 11 – September 9, 2007