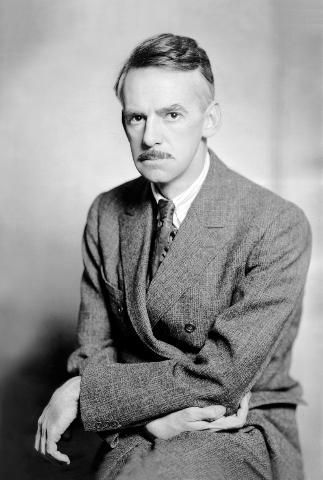

Tragedy of Eugene O'Neill

Family Ravaged as Long Day's Journey Into Night

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 04, 2016

Over the past two nights we watched the 1962 Long Day's Journey Into Night, directed by Sidney Lumet, on Turner Classic Movies.

The film stars Katherine Hepburn as Mary Tyrone, Ralph Richardson as her husband, James, and Jason Robards, Jr. as their son Jamie, Dean Stockwell as Edmund with Jeanne Barr as Cathleen.

The play, which was written in 1941-42, was among the last works of Eugene O'Neill (1888-1953). For the last decade of his life he was too ill to work. He suffered from the progressive stages of alcoholism with tremors that made it impossible for him to use a typewriter. An effort to dictate proved to be futile.

During this time he had a mutually destructive relationship with his third wife Carlotta Monterey. There were instances of abuse and vengeance. Like his mother Mary she had become an addict. Under circumstances that are unclear a number of manuscripts were destroyed including an intended cycle of eleven plays focused on an American family. Two survived A Touch of the Poet (1942) and More Stately Mansions which was found in his papers. It was first performed in 1967.

In the spring of 2015 the American Theatre Critics Association met in New Orleans. The convention overlapped with the annual Tennessee Williams Festival. We attended a number of plays, readings, and events. This included a lecture by John Lahr, a Williams biographer, and former theatre critic for the New Yorker.

Astrid and I both read Lahr's book which was helpful when we attended the annual Tennessee Williams Festival in Provincetown. We plan to again cover the festival which this September will merge with works by O'Neill. The latter launched his career circa WWI with the Provincetown Players which later reformed Off Broadway in New York. The company produced a number of his early plays.

This past winter we both read "Eugene O'Neill: A Life in Four Acts" by Robert M. Dowling. As a Christmas present a poet friend gave me a copy of Long Day's Journey Into Night which we both read.

The film is faithful to the text and it was exhilarating to feel the words leaping from the page into the performances of truly magnificent actors. Hepburn was nominated for an Oscar for her role.

Through Amazon I purchased the three volume compilation of O' Neill plays and so far have read a number of the earlier and less familiar works.

During my high school years I particularly enjoyed reading plays. The first O'Neill play for me was The Iceman Cometh (written 1939, published 1940 and first performed in 1946). Imagine being a teenager and trying to make sense of Harry Hope and that stunning collection of dreamers, drunks and tarts.

A couple of years ago during an ATCA meeting in Chicago we saw the Goodman Theatre production of Iceman which later came to New York.

During his time in the Berkshires I engaged in a dialogue about African American roles in O'Neill plays with John Douglas Thompson who played the role of Joe Mott. It was based on a real life friend of O'Neill who often helped him to recover from down and out binges.

Previously I had seen Thompson when he performed the lead role of The Emperor Jones (1920) Off Broadway at the Irish Repertory Theatre. He discussed a third play, All God's Chillun Got Wings (1924) about an intermarriage It was among the plays that I have read recently.

Thompson states that O'Neill was unique for his time in his empathy and insights in matters of race. He wrote realistic, unstereotyped roles for African American actors. The first production of The Emperor Jones at the Playwrights Theatre starred Charles Sidney Gilpin. There were a number of productions but they argued over the use of "nigger" in the text which Gilpin was changing to negro. O'Neill insisted that it was essential to his work.

They came to an impasse and Gilpin was replaced by the younger Paul Robeson. The New York and London productions established Robeson's career and marked the downfall of Gilpin.

Before committing to playwrighting, having dropped out of Princeton and failed in an attempt to follow his father on stage, O'Neill spent rough years as a merchant sailor. Like the novels of Joseph Conrad this was an inspiration for a number of plays. It was a trope for The Hairy Ape (1922) which I read recently. The female role was performed by Carlotta Monterey his later wife.

While focused on coming to grips with the works of O'Neill they have been a part of a lifetime of experiencing American theatre. There was a moving performance of A Touch of the Poet at American Repertory Theatre some years ago. It was among the plays I had read as a teenager.

Here in the Berkshires, last summer, there was a stunning Williamstown Theatre Festival production of Moon for the Misbegotten (1941-43) which closed in 1947 before reaching Broadway. With inventive casting it featured the magnificent Audra McDonald as the Irish daughter of a tenant farmer in Connecticut. It was written as a companion to the Tyrone family in Long Day's Journey Into Night.

Currently that play, widely considered to be O'Neill's finest and on the short list of the American canon, is currently staged on Broadway with an all star cast. Jessica Lange has been nominated for a Tony for her lead role as Mary. Also this season was a failed production of his one act play Hughie (written 1941 first performed 1959). Oscar winner Forest Whitaker was poorly reviewed in his first Broadway performance.

From its inception Long Day's Journey has been the subject of controversy. One may say that it is written in O'Neill's blood. The characters are modeled on his own terrible family life. The facts of mediocrity, failure, morphine addiction and alcoholism are all too true.

To read or view this gut wrenching play is to live vicariously as a voyeur absorbing, I can't say enjoying, the misery of others. It plunges us into the heart of darkness that is a part of so many, not all, of us.

No, that is not my family, but his courage and perhaps vengeance in writing the play shapes and informs the intentionality of all, post O'Neill, who use the circumstances of personal life as a template for creative work.

It begs the question of who owns the rights to our lives when it is used in our work? What is the moral dilemma when use of our experience causes damage to others? Of course there is also the matter of two sides to every story. Art does not allow for rebuttal although damaged family members may write their own Mommie Dearest memoirs. Consider the vindictive Life with Picasso by Françoise Gilot.

In a sense all artists tell their own story. This realism in drama, according to scholars, O'Neill found in the works of Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) and August Strindberg (1849-1912).

It is significant that Thompson, a master of classical theatre, is currently performing Off Broadway in Ibsen's The Doll's House and Strindberg's The Father. His interest in O'Neill has inspired exploring the sources that inspired him.

Arguably, O'Neill and Williams are the twin towers of 20th century American drama. By the end of their lives, having ravaged their inner selves for their work, combined with drugs, alcohol and forms of abuse by and against loves ones, they died as ghosts. They had been consumed by their art.

In a Faustian pact with their muses was it the price to be paid for violating the privacy of their family, friends and loved ones? For Williams the argument focuses on his first great success The Glass Menagerie (1944).

When O'Neill wrote the wrenching and cathartic Long Day's Journey Into Night, arguably an exorcism, he left instructions that it not be published until 25 years after his death and never be produced.

His widow and literary executor, for reasons that are complex, handed over the manuscript to be published and first staged, just three years after his death, in Sweden in 1956. It earned O'Neill his fourth, posthumous, Pulitzer Prize.

While this violated his last will and testament it presented to the world the masterpiece of one of our greatest playwrights.

Reading deep into O'Neill it is evident why that play stands apart. There is merit in reading every one of his plays but at times the pleasure comes in small increments.

There is a dense oeuvre to confront comprising some 52 published works including his juvenilia for early Provincetown Players. Perhaps that will be an aspect of the coming festival which has produced the always interesting ephemera of Williams.

As artists Williams and O'Neill, in the Catholic sense, paid for their sins. As in Williams' Suddenly Last Summer (1959) they were cannibals who feasted on the flesh of others at a terrible price. Perhaps they were monsters and certainly their works could be monstrous.

Compared to these serial killers as artists, however, much of what passes for art is ultimately so boring and bourgeois. In order to create compelling art one must be a noble savage.

We may love and admire the art, plunge into it for humanity and insights, find comfort in its pain, but like Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray the portrait of the artist ain't always pretty.