BIFF Two

Part Time Fabulous, On the Ice, !Woman Art Revolution

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 06, 2011

Part Time Fabulous

For Alethea Root, a Berkshire native, her career as a director started at Monument High School. Standing in front of the Beacon Cinema in Pittsfield, just before the Sunday morning screening of her first feature film Part Time Fabulous, Root commented that the play she directed was the “first to make a profit” for the high school.

Let’s hope that luck prevails for the compelling and insightful film she wrote with Jules Bruff, who stars in the film as a woman suffering from clinical depression (a state of depression and anhedonia so severe as to require clinical intervention.) When Bruff, who is also from the Berkshires, joined the dialogue they agreed that the film has a narrowly targeted subject and potential audience, but they want “to make films that matter.”

From Bennington College, where she was enrolled in a combined undergraduate and graduate program, Root did not pass go and collect $200. She opted instead to head straight for Hollywood. She has been working her way up the film industry which has paid off at a remarkably young age with the chance to make her own movies.

Using the now ubiquitous technique of seeking funding on line (it worked for President Obama), she raised the money for the film through many small donations. At the Sunday morning screening of the Berkshire International Film Festival, the audience was filled with many friends, family and local angels.

During the post-film talk back session, Bruff identified a woman asking a question as “That’s my high school English teacher.” It got a good round of applause.

Before the Sunday morning screening, on a bright sunny day, we asked Bruff to what extent the film is autobiographical? While based on her own experiences, she was diagnosed with clinical depression at the age of 20, she and Root focused on shaping the story, with its universal messages, into a viable dramatic film.

Whether a film with such niche appeal will find traction and distribution remains to be seen. They told me that Bruff won an award for “Best Actress” at the Monaco Film Festival which is regarded as a satellite for the more prestigious Cannes Film Festival. The screening in Pittsfield (BIFF has a mandate to support Berkshire talent) represented the U.S. Premiere. It has also been shown to and well received by mental health organizations.

As a trope, from the first dialogue between Root and Bruff about the project, there was a decision to combine head shot interviews with individuals who suffer clinical depression, and a dramatic narrative about the fragile, challenged relationship between Mel (Bruff) and a rugged, heavy drinking and smoking older guy, Don (Bjorn Johnson). They met on vacation in the Caribbean, and he has arrived to begin where that left off.

As the many “real people” tell us, both men and women, forming and sustaining relationships is difficult if not impossible. Managing the disease requires a tough regimen of therapy, medications, exercise, adequate rest and relief from stress, as well as a healthy diet. Often individuals self medicate with drugs and alcohol. This may mask symptoms, but it also nullifies the impact of prescribed drugs.

Initially we see Mel guarded but accepting of Don. Even though she is sensitive to his smoker’s breath and beer drinking that threads through the day. More importantly, he loves and supports her when her symptoms are revealed.

There is an intense use of chiaroscuro in the cinematography. Darkness prevails when Mel falls into deep depression. These are mostly shot in the bedroom or on the couch when she insists on sleeping through the day. When Don leaves, for the second time, that is depicted as days on end. We also see the disorder of the apartment with laundry strewn about and dishes in the sink.

It is only when Don finally leaves that Mel follows the regimen that he had worked out with her. By the end of the film, as in true life, Mel/ Jules is not cured but now able to manage chronic depression. The film concludes, in bright sunlight, with her pursuing a career as an actress and writer. In the talk-back, she discussed several projects including a short film in production.

Root apologized that for technical reasons the film was projected as too dark. Some of the nuance of Bruff’s performance was lost in the shadows. To my eye, it played just fine, and the analogies of light and dark were most effective.

As a “film that matters” Part Time Fabulous faces a conundrum. While it informs us of a compelling issue, does it have a broader appeal as entertainment? Is it the kind of film that a sufficiently large audience will pay to see? Will it prove to be the “calling card” film that makes its way around festivals and gains the attention of producers? In the tough world of filmmaking, if your first film doesn’t make money, it’s hard to fund the next one.

Yes, this was an absorbing and well made film. Seeing it is enriching both for its insights as well as fine performances by Bruff, Johnson and John Combs who has a minor role as Mel’s dad.

The interspersion between individuals telling their own stories and the dramatic sequences added depth and credibility. But it also created a hybrid between a documentary and a drama. On a much smaller scale, it reminded me of Reds. Which, come to think of it, isn’t a bad comparison.

On the Ice

One of the challenges of a festival with an array of options comes down to making decisions. Through an evening and two days, we chose well. When you make the decision to see a particular unknown film it is based on a thumbnail in the catalog. You have to trust the taste of the curators. In general, artistic directors, like Kelley Vickery, spend a year of attending a circuit of other festivals, and viewing a deluge of submissions to make the final selection. You come to trust in the taste and track record of a festival. Which, in the case of BIFF, proved to be excellent for the eight films we viewed.

The film On the Ice, shot on location by writer/ director Andrew Okpeaha MacLean in a small Alaskan village proved to be riveting. MacLean’s first feature film tells the story of two teenage boys trying to lie and cover up a quarrel, On the Ice, which resulted in an accident and manslaughter of their friend James.

Of the two boys, best friends, one is bright, introspective, almost emotionally catatonic and headed for college. The other is extroverted, likeable but dufus.The seventeen-year-olds are Qalli (Josiah Patkotak) and Aivaaq (Frank Qutuq Irelan). Qualli represents the hope of the Inupiaq village as one who will make something of himself and break the cycle of poverty. Aivaaq, emotional and out of control, has knocked up his girlfriend and is destined, like his father, to die young of drug and alcohol abuse.

Although the actors appear to have limited training, and deliver mostly stilted performances, they are authentic to their culture and elevated by a complex, well-crafted script. There are enough plot twists to keep us entirely absorbed. We also are privileged to gain compelling insights to the issues and challenges of survival and traditional cultural values in such a harsh environment.

Like teenagers everywhere, the kids rebel by partying including drinking and smoking pot. At a raucous house party, we see the boys taking turns performing rap to a rhythm track. There is a sameness about kids everywhere that allows us to identify with these teenagers.

But there is something unique and different about On the Ice. While the village is dirt poor, every boy and man appears to have a snowmobile. It is the contemporary upgrade of dog sleds. The wise dad of Qalli is superbly played by Teddy Kyle Smith. He is a master hunter and tracker. In many aspects, he is a paradigm for the traditional values of the culture and a compelling role model for his son.

When the accident/murder of James occurs, the boys decide to dump the body and snowmobile through a hole in the ice. They then shovel the bloody snow into a trash bag and smooth over the spot.

Given false information, Qualli’s dad leads the search and rescue team coordinating with ice and helicopter. It entails an analysis of ice flow and conditions that call off the search. His wife urges him to let it go and accept the story of the boys. He responds to her, would you tell me that if it were your own son?

He continues the investigation and finds the body. He lures the boys onto the ice and confronts them with the evidence including a knife wound in the neck. Leaving them he states that he can’t tell them what to do.

The environment itself is a major force in the power and success of the film. It was a hit at Sundance and Berlin which is how it came to Pittsfield. One of the compelling reasons for attending festivals is for the opportunity to see projects such as this which fall off the radar screen of your local trash oriented megaplex.

!Woman Art Revolution.

As a male art critic, I took one for the team sitting through Lynn Hershman Leeson’s documentary history lesson !Woman Art Revolution. It is an important and compelling topic, the rise and progress of feminist theory and activism in the fine arts from the late 1960s to the present. Having lived through that era this was mostly familiar information, but there was the compelling advantage of having it organized and summarized in 83 minutes.

Leeson informs us that she shot many of the interview segments over several decades in her living room “on that couch.” One segment with Judy Chicago, a key player in the history and narrative, was shot in a lady’s room because of “the acoustics.”

We learn that Leeson was able to complete the project, mostly through self funding, because work that was poorly valued initially finally sold for 9,000 times its original price. It is revealed that decades ago a collector could buy the work of 30 leading, and then obscure women artists, for the cost of a single work by an established male artist.

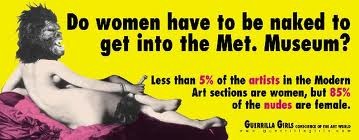

Of course that is no longer true. In historic footage there is a sequence where visitors standing in front of a New York museum are asked to name three women artists. Most can’t. Pause a moment and take the test. Of course, if you are an artist, male or female, it should be a no brainer. But for the non art world general reader, well?

While there is no question about the importance of the topic, we just wish that the film were better made. Yes, bravo to Leeson for funding and making the film, but her craft and insights are limited. In an all too obvious conflict of interest she inserts her own work into the narrative on equal footing with more interesting and important artists. She justifies this questionable decision by telling us that she will not submit to the “politics of exclusion.”

Which, I guess, is another way of saying “It’s my party and I can cry if I want to.”

Of course, in hindsight, many of the facts that drive the film are simply horrendous. Today, in a more progressive art world, the extent to which women artists were excluded and marginalized in the past is just ghastly.

We hear the late Nancy Spero, now viewed as an icon or her generation, tell the sad and amusing story of taking her work to the then dominant Leo Castelli Gallery. There it was viewed by Ivan Karp, Leo’s gifted and generous second in command. Karp virtually founded Soho by establishing his O.K. Harris Gallery. Many of us have our own Ivan Karp stories. He is one of the few in the New York gallery scene who will look at virtually any artist’s work. As long as it doesn’t entail a studio visit. He is also known for giving countless artists, men and women, their first New York shows.

Spero describes putting the portfolio on the floor in front of Karp (there were tables and empty pedestals in the space) and having to “genuflect” to this powerful gallerist when stooping to turn pages. She describes the experience as “humiliating.” Well, actually, it mostly is for all of us.

In the era that Leeson focuses on, few if any women were shown in major New York galleries and even fewer made it into major museums. We learn of the seminal efforts of activists including Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro, Faith Wilding, dancer Yvonne Rainer, Hannah Wilkie, and Carolee Schneeman. Chicago and Shapiro were prime movers but also clashed and feuded. It seems that no revolution is devoid of dissent in its leadership and among its ranks. But as front runners, they changed the rules and opened the doors for later generations. There is an interesting sequence with the much younger art star Janine Antoni. She was asked if she knew the work of certain early feminist artists. When she went to the library to research the topic, she was shocked at the lack of published information.

Important feminist artists such as Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Marina Abramovic and Yoko Ono are represented by brief images of their work but were not included with interviews. It seems that Leeson lacked the clout to get to many of the key players. Where is Louise Bourgeois? Arguably Louise Nevelson, Agnes Martin, Lee Bontecou, Jay DeFeo, Harriet Casdin Silver, Alice Neel and Helen Frankenthaler, to mention just a few, were excluded as not “feminists.”

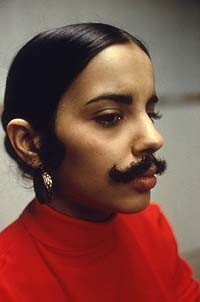

The film includes interviews with African-American artists Adrian Piper, Howardena Pindell, and Faith Ringold, as well as images of work by Betye and Allison Saar. But no Native American artists are included not even Jaune Quick to See Smith or Kay Walking Stick. Hmm. Ana Medieta is the only Hispanic artist and there is just a blip on Asian women other than Yoko Ono. Leeson, it would appear, was too absorbed with talking about her own work.

Because of a lack of a coherent history, which is now quite different at the academic level, many young women artists were faced with reinventing the wheel. Surely Leeson’s film will be a standard DVD and talking point in the ubiquitous Women in Art courses taught in virtually every liberal arts college and art school. One just wished that it were smarter and more provocative.

The footage I most treasured was with the founder of the New Museum, Marcia Tucker. She started the museum within weeks of being fired by the Whitney Museum after a tenure of eight years. She was the Whitney’s first woman curator. Lowery Stokes Sims, an African American, was the first woman curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She went on to found the Studio Museum of Harlem. I have corresponded with and interviewed Sims who is brilliant and engaging.

Marcia, who I knew during a semester at the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU was truly amazing. She was kind enough to include me in an exhibition at Max’s Kansas City. We all loved her candor, charisma, and most of all, compelling humor. She had the great gift of brushing off adversity and making us laugh with her at the absurdity of the art world. Her exhibition Bad Girls got hilariously awful reviews and ended up being emulated by museums all over the world.

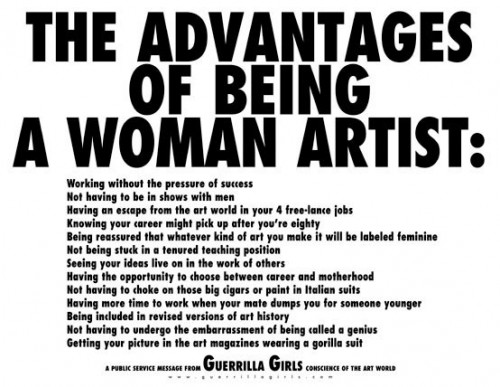

She may have been a force behind the outrageous stunts of the Guerrilla Girls. They continue to remain anonymous but with dead on irony, like Joshua at Jericho, the walls of the all white male art world came tumbling down. What a hoot.

Then there was divisive conflict surrounding the death of Ana Mendieta (18 November 1948 – 8 September 1985). The Cuban-born performance artist often depicted abuse and murder of women in her work. When she was efenstrated following a night of argument and drinking (witnessed in a restaurant) her husband, the minimalist artist Carl Andre, was charged with murder. At the time of his arrest, he was drunk and incoherent.

The art world establishment rallied around him, and prominent friends, including Robert Raushenberg, helped to pay for his expensive defense. In a sensational case that is often compared to the O.J. Simpson trial, Andre was acquitted.

In the film, we learn that the Guerrilla Girls were split on how to respond. On camera, a woman states that “The Guerrilla Girls couldn’t even make a fucking poster for Ana.” But there is compelling footage of a later protest. Xeroxes of her face were dropped onto one of Andre’s floor pieces in a museum exhibition.

Another matrix of the film is the controversy that surrounded Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. We are astonished and amused by debate about the allegedly pornographic piece on the floor of the House and Senate. Women voters were successful in rallying to help kill the bill in the Senate.

We all should know a lot more about feminist art history. If you are looking for the Cliff Notes why not start with this movie.