More Dishwasher Dialogues

Rauschenberg, Pollock, de Kooning and ‘Lit Dé’

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Jun 08, 2025

SO, THIS IS A RAUSCHENBERG

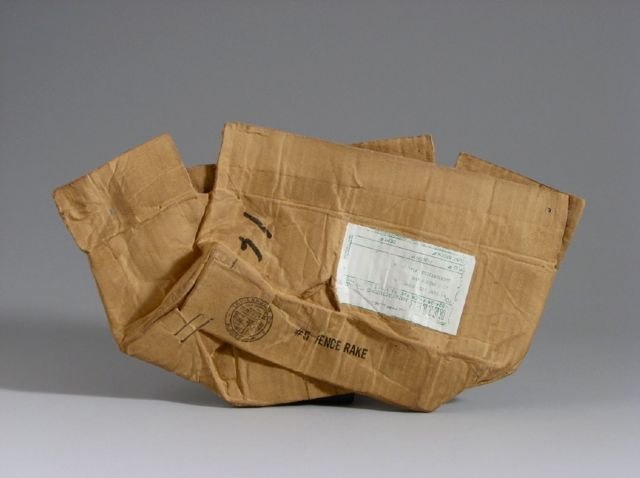

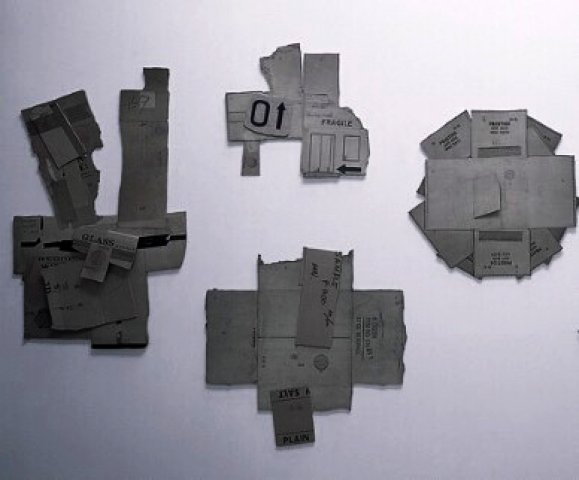

Rafael: One afternoon we went to see a Robert Rauschenberg show at the Galerie Sonnabend on the rue Mazarine. It consisted of , among other things, flattened, used, tattered, cardboard boxes stuck to the gallery wall.

Greg: I remember those boxes. One box above all. They were in a smaller room off to the side with several of his smaller studies and pieces. The main gallery was exhibiting some of his large fabric hangings.

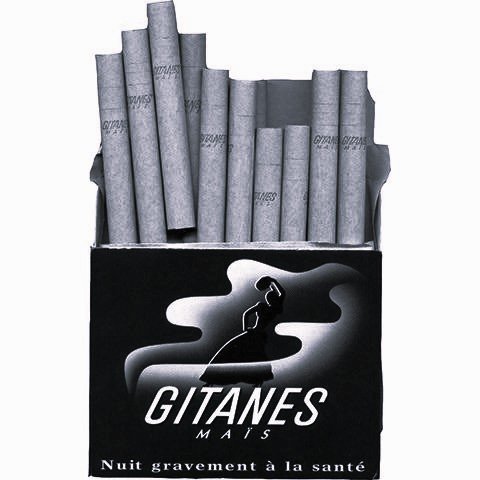

Rafael: These were some textile pieces. I never found them interesting. The gallery was empty except for a few young people puffing away at their yellow papier maïs cigarettes. Horrendous things, Gitanes, strong tobacco but in vogue because Sartre smoked them, and the artsy-fartsy intéllo people smoked them even if it choked them. Real intellectuals smoked in those days. If you didn’t have a cigarette stuck in your beak you were not a bona fide intellectual.

Greg: I failed the cigarette test badly. I do recall the gallery being a large space with only a few people in it. We looked at the hangings for a few minutes. You gave me a comprehensive summary of who Rauschenberg was, where he came from, his previous work: what was good; what was not; what was bullshit. You knew the details. Then we went into the second room. I have a solid memory of the moments there.

Rafael: So do I! You looked at the stuff, went up to one of the pieces, when nobody was looking.

Greg: The flattened carboard boxes were the most notable objects. Notable in my mind, for what an artist could call art. The sheer confidence. The utter entitlement. It was not the work of a novice. Not because a novice couldn’t do it. A guy who could only draw stick figures could do it. I was only vaguely aware of others being there. I was aware of you standing beside me. We were both staring at the crushed box for a minute or so. It looked like a cardboard box (size of a 12-bottle wine box) compacted by someone just stomping on it. I can’t remember what the title card said or if there was one.

Rafael: These cardboard pieces were called the Cardbird Series. Don’t ask me why.

Greg: The cardboard was covered in multiple creases where it had collapsed and been misshaped. It had then been glued to a sheet of plywood and the plywood cut to the flattened dimensions of the box. Easy to hang. Although it was just laid out flat on a table at the time. My memory is that I said to you, ‘so this is a Rauschenberg?’ Then I dug my thumb nail deeply into the cardboard and made a crease maybe an inch long. “Now it’s a Rauschenberg and Light”.

Rafael: Some more people had walked in. They were the arty types, elegantly dressed, with a touch of grunge, going oooh and aaah, and Bob this and Bob that. They walked up to the piece you had incised.

Greg: After I did it, I was aware of some people standing behind me. I remember hearing a woman’s audible gasp which I interpreted as something like the response to someone desecrating the Mona Lisa. I remember saying to you. “I dare anyone to look away for a moment then look back and find the actual mark I made.” It had disappeared into the field of crumpled cardboard marks and folds and creases.

Rafael: One of the men, who hadn’t seen you denting the cardboard, looked at the work a long time, then bent forward and stared at your mark in the cardboard, and said, ‘oh this is so like Bob, isn’t it, making such subtle aesthetic choices, a scratch and a crease here and there’. But in my pantheon of 20th century artists Robert Rauschenberg stands out because his work, irreverent and sacrilegious, had given us twenty-year-old’s in art school a joie de vivre, much needed after the overly-serious, and often pretentious angst and depressive work of the Abstract Expressionists. With the exception of de Kooning. Rauschenberg danced wearing roller-skates, sculpted with stuffed chickens, painted with unmarked cans of house paint.

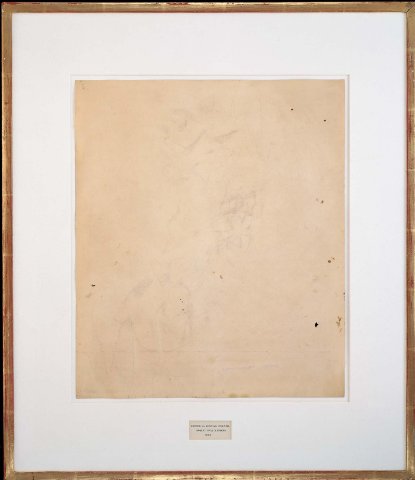

Greg: That is good to hear. I did not feel especially uncomfortable about the incident then nor have I since. I have told the story many times and often heard similar gasps to the one behind me on the day. And I have been castigated for it. It has raised many discussions about the nature of art. I subsequently learned that Rauschenberg had himself erased a Willem de Kooning drawing and exhibited it as an almost blank piece of paper. So I feel less affronted by my younger self. Not that I knew any of that at the time. And Rauschenberg did get de Kooning’s permission “because I understand the idea”. And Rauschenberg credited him in the title. I have never requested any credit for my contribution. Maybe I should.

Rafael: We walked out of the gallery, and I laughed and said, ‘I’m sure Bob wouldn’t give a shit, and like any self-respecting Dadaist, he’d probably say you made it better’.

Greg: Because he would understand the idea. And I did make it better. But one would have to have a highly trained and advanced artistic eye to fully understand how.

Rafael: What makes it better? Nothing. The Dadaists didn’t believe in any criteria. Prophetic. Today anything goes, as we well know. You, my friend, made it different, and that’s fine, okay, good, terrific. Cutting my canvas at the customs office was pure Dadaism. Maybe Bob would have burned a few of his pieces, given them some color, you know that brilliant color spectrum you get from blackened cardboard. That’s Dada too.

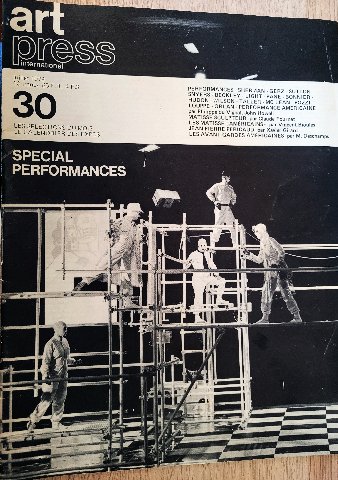

Greg: A year or two later, I was reminded of this experience of cardboard art, when we took off to Lyon for a few days. We were invited to take Black to Black to the Symposium International de Performance, in Lyon. And they were providing some financing. My memory is that the performances were in a wide array of different spaces throughout a large industrial building.

Greg: We attended quite a few performances including a naked man trapped in a glass cube. His performance consisted of smashing his way out, through what quickly became a web of lethal shards of glass. It took him about 20 minutes to exit, by which time he was covered in his own blood. The most memorable event for me (possibly not for the right reasons) was the artist from Montreal. We ran into him at a large stage door exit. His performance consisted of taking a twin bed on wheels (furnished with pillow and blanket) out for a walk. On the bed was a single very large white cube, painted with black dots so it looked like a single giant die. He told us he was about to start pulling the bed on an eight-hour journey through the streets of Lyon. As you know, a bed in French is lit and a die is dé. He was taking ‘lit dé’, a pun on the word ‘l’idée’ (the idea), to the people of Lyon. As far as I could gather from talking to him, that was it: he was taking the proverbial horse to water. Or water to horse? Nothing more. That is art.

Rafael: If some museum pays a million bucks for it, you bet. Suddenly it’ll be in the art history books and your kids would have had to memorize the date and title for their final exam in art history survey courses. You think dripping paint on a canvas à la Pollock is much different? I don’t. Or spending your entire life painting black canvases? And then the state hires you as a professor at a whopping salary because you’re well known, to teach gullible students to do black canvases. That’s not only unfair and boring, but unethical too. The young students will swallow anything, especially in fine art. I would say modern art since the Bauhaus is a huge Ponzi scheme. Will it collapse in our lifetime? I doubt it.

Greg: Whether or not the citizens of Lyon ever swallowed ‘the idea’, is anyone’s guess. I still refer to art I find ‘suspect’, like a crushed cardboard box or a totally black canvas, as simply ‘lit dé’. But part of me liked the bed-die piece. It clicked for a short moment as he left the building. Who am I to criticize? I have many of my own ‘lit dés’ to defend. Not the least of which is a wayward thumbnail impression.

NEXT WEEK: SLEEPING WITH ROTHKO