Stefan Stux Closes New York Gallery

Started in Boston in 1980

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 12, 2016

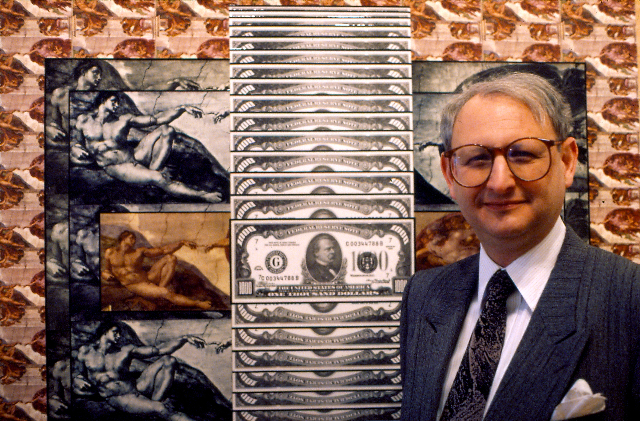

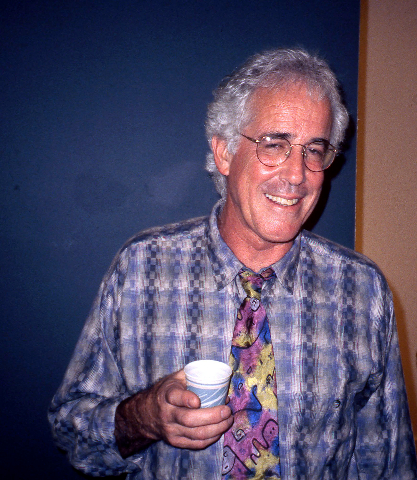

Now 73, NY gallerist, Stefan Stux and his partner Andrea are taking early retirement with the closing of their gallery at 24 West 57th Street.

With dramatic swings of the pendulum the former blood researcher was sanguine when we spoke looking back on some 35 years in the art game.

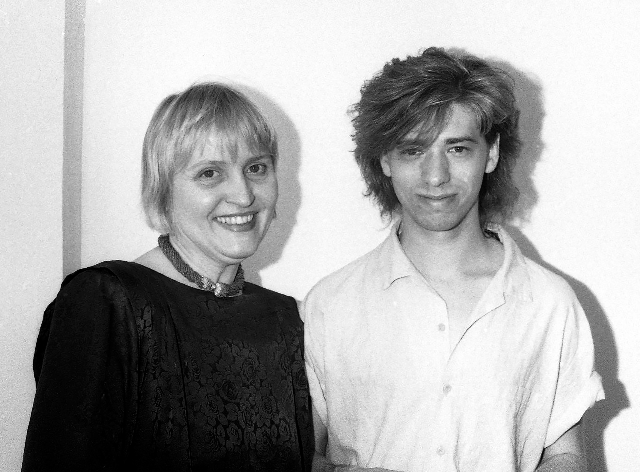

By e mail he confirmed the closing and requested vintage images of the founding years with his deceased wife Linda.

This has entailed digging into a thick file folder of memories. During Boston’s cultural revolution of the 1980s, with a surge for the arts and rock music, Stefan and Linda, in alliance with David Ross revitalizing a then moribund Institute of Contemporary Art, were in the thick of it.

It seemed like a triumph for all of us when Stux artists, Doug Anderson and the Starn Twins, were selected for the prestigious Biennials of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Having artists on a national level prompted opening a New York annex on Spring Street. For a time both spaces were maintained until the Newbury Street space was closed.

The initial director for the New York venue was Anne Pasternak who is now the director of the Brooklyn Museum. Two other Ann’s, Louer and Lacaise, continued to run the Boston gallery.

When Stux closed Louer became employed by Zoe Gallery whose owner, Gooz Draz, embarked for a round-the-world romp leaving the venture with Michael Beauchemin sharing management. For a time the festive mood of Stux continued at Zoe but with the same result.

When I wrote an overview of the Stux gallery history ten years ago Stefan told me that like Leo Castelli he would never retire.

He said that if possible he would continue as a private dealer.

I asked about his future plans and resources. The response was unclear and what remains of his personal collection has been sold to “Live to fight another day.”

He described the endgame as the result of an approach of ‘idealism’ in dealing with artists.

We briefly discussed his strong feelings and attachment to the Boston years. As a final project he is assembling an extensive on line website. The intent is to document the history of the gallery.

In some aspects it is a race against time because “We are losing staff. It is understandable that they are leaving to seek new jobs.”

Research revealed that the gallery has shown some 500 artists in individual and group shows. All of these participants will be listed and there will be a focus on a short list with two images each of the more established artists.

This kind of closure is uncommon in a business where most dealers simply close the door. It reveals that for Stefan this has been more than a business and reveals his humanistic instincts and concerns.

In the decades since he departed from Boston we have remained close. Initially, from time-to-time, I would stay with Stefan and Linda during visits to New York. I warmly recall Stefan in a smoking jacket with brandy and cigar regaling me with colorful anecdotes in his distinctive Romanian accent.

When the gallery gave up its Boston space there was an initial attempt to show its artists in New York. It was soon obvious that this was not a viable option. That resulted in resentment.

This past year one of those artists, Gerry Bergstein, was given a show in the New York gallery. It was a thrill to enjoy this event.

As was the news this past year when former Stux intern, Anne Pasternak, was appointed director of the Brooklyn Museum. She made her way to that top position through Real Art Ways in Hartford and then as director of Creative Time in New York.

Back in the day it was fun to hang out with her. I recall being amazed by how her little toe crossed over the adjoining one when she took her shoes off and let her hair down. Anne, who had an endearing ability to laugh and smile, taught me how to stick a wedge of lime into a bottle of Corona. Anne is married to Mike Starn. His twin brother Doug was best man at their wedding.

This is just a part of the colorful legacy of Stux Gallery. What follows is a reposting of the gallery history.

Berkshire Fine Arts, October 29, 2006

It was an early Saturday morning in Chelsea arriving at 530 West 25th Street only to find Stux Gallery closed. I had rushed to make the appointment having found a $115 dollar parking ticket on the windshield. The night before it seemed there was sufficient distance from the hydrant. It was getting late for a 9:30 appointment as I tried to repark the car and considered taking a cab cross town from Gramercy Park.

The plan had been to start talking before the opening of the gallery. At about 10 a gallery employee found me sitting on the steps when he opened up. There is a narrow space off the gallery where the staff works at computers. A young woman, the third of a staff of three, arrived with coffee. She was working on the bio of the recently added Australian artist, Tracey Moffat.

Stefan and his companion, the director of Stux Gallery, Andrea Schnabl, arrived. She settled into the front office while he took me to an upper level near the private show room and storage area.

After several years in a cramped rabbit's warren on an upper level of a gallery building on 20th Street Stefan is enjoying a generous street level space. After 26 years of tumbling about in the art world cyclone he is back on his game.

There have been the boom years when Stux was recognized on the short list of "hottest galleries" first in Boston then again in New York City. As well as the bust of traveling up river in the heart of darkness.

High and low he has always been a colorful and controversial individual who inspires extremes of passion. Artists have complex relationships with their dealers. But as Stefan pointed out during a more than two hour meeting they fail to realize that artists and their dealers are all in the same boat. Nobody sends flowers and get well cards to gallerists when they go belly up.

It was insightful to reflect on the past having known Stefan and Linda, who succumbed to cancer in 2000, through most of his career as an art dealer.

During the years in Boston they were the charismatic epicenter during a time in the early 1980s inspired by a revitalized Institute of Contemporary Art under David Ross and a lively movement of emerging artists. The best and brightest showed with their gallery.

There was a sense of communal pride when Stux artists, first Doug Anderson and then Mike and Doug Starn, were included in Biennials of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Later the gallery moved from a hole in the wall on Newbury Street in Boston to ever grander space in New York which at its peak employed a staff of 20. I recall Stefan taking me on a tour of separate spaces (for special clients only) dedicated to the artists Andres Serrano, Lawrence Carroll, Vik Muniz, the Starns, Holt Quentel and others.

After the crash and a two year hiatus of private dealing, in 1996, he opened on 20th Street, with a staff of one, Pearl Albino, and introduced new artists Inka Essenhigh, Su-En Wong, Jennifer Reeves and Jay Davis. Today the gallery represents just over thirty artists from elder statesmen such as op artist Julian Stanczak, sculptor Dennis Oppenheim, and surgical conceptualist, Orlan, through photographers, Manabu Yamanaka, Margi Geertinks, Ike Ude, Michael Timpson, painters Thordis Adalsteinsdottir, James Richards, Angelina Nasso, Nicky Nodjoumi, James Busby, Heide Trepanier, and Darren Wardle as well as the sculptor Clay Ervin.

Enduring the twists and turns of the art world has been challenging but Stefan's life story is even more remarkable. It starts with the miracle of an Eastern European Jew born during World War Two, surviving the Holocaust, and then growing up under Communism. Or, as he put it, enduring "One totalitarian regime followed by another." With that personal legacy he grew up with a passion to make something of his life.

When they arrived at Brandeis University, in the early 1980s, where he took a job as a researcher the eccentric couple became regulars at art openings. Linda was particularly memorable in a paramilitary phase as a performance artist. She wore combat camouflage with cap and boots. Then, as now, Stefan spoke in a thick Romanian accent but back then even more so. Just what to make of this odd couple who showed up at all the openings? Around that time he was going through a midlife crisis.

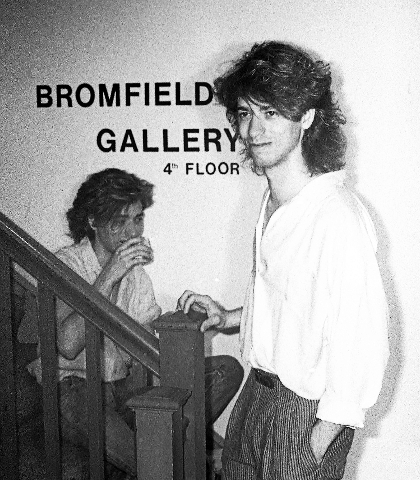

His work as a medical researcher was not satisfying compared to an overwhelming interest in contemporary art. He sought out a space in the artist loft district on Boston's A Street. But during several visits to the gallery operated by James Donnelly, then the largest in the city, during posted hours it was never open. On the third try, about to give up, he found it open and engaged in a lively dialogue with the young gallerist.

In the ensuing conversation Stefan asked what was the point of having the largest gallery in town if nobody ever visits? A plan was hatched to become partners and move to the third floor of 36 Newbury Street, in the trendy first block, diagonally across the street from the legendary Ritz Hotel.

"I knew nothing from nothing," he recalled. But he sought out the advice of dealers in an industrial area on Congress Street. They included Lopoukine/Nayduch, Culter/ Stavaridis (Bess Cutler moved to New York and closed during the bust) and Helen Shlein. It was Shlein who proved to be a mentor and a "saint." "She was a true pioneer," he recalled. She asked why on earth he wanted to open an art gallery? "I got the bug," was the laconic answer.

In the meantime he left Brandeis to join the faculty of the Department of Pathology of Harvard Medical School pursuing research in the field of Immunogenetics. Linda taught math at the venerable Boston Latin School. In their spare time they were putting sweat equity into renovating the long narrow space. They worked full time jobs in addition to running the gallery. As Stefan told me years ago "If you want to run a gallery you have to have deep pockets." They didn't. It was almost a year before they made their first sale.

While they were making a decent living through combined income the cost of maintaining the gallery was draining resources even with relatively affordable rent and a modest lifestyle. But Stefan was pissed and ever more determined when his brother asked "How long are you going to run your museum?" The answer was a defiant "Forever." Adding that "Like Leo Castelli before me I will never retire."

There are many emotional shifts and nuances to spending time with Stefan. He can turn dark and speculative offering complex philosophical insights. There is his wonderful ability as a superb raconteur. And moments when he takes a manic, innocent glee at his own jokes and stories. He can be hilariously warm and funny.

"The story of my birth is relevant to what I do in art," he said. "My being alive today is a fluke of the history of World War Two. And the geopolitical idiosyncrasies to survive being born in Eastern Europe in 1942 when millions of others were gassed in the death camps of Nazi Germany. It turns out that the particular place where I was born was under the control of the Romanian Government which was corrupt and fascist. The Jewish community of my town was rich and the deal was simple. The Government decided that it was in their best interest to milk the Jews dry before handing them over to the Germans. They approached the Jewish leaders and conveyed that they would try to hold back the Nazis but it will cost you. Every month there was a steep ransom of cash in order to stay alive. The community was bankrupt when the Russians finally arrived in 1945.

"I was born in October 1942 and conceived in January of 1941," he said. "My father had been taken to a labor camp. There he was treated as a convict. But he had enough resources, he had a prosperous business and was required to take a non Jewish partner, to offer a bribe to be allowed to take a furlough from the camp. It was during that visit home that my mother became pregnant which became a crisis. What to do under the circumstances? My father decided that 'If we live he lives. If we die he dies.' So that's how I ended up sitting here as the result of a mélange of a lot of weird stuff since so few of my peers survived.

"So, for me, the idea of freedom of expression became something strong and personal. It was a visceral physical matter to me. When the Nazis started in the 1930s nobody spoke out. When they came to take away the Commies people said 'We aren't Commies so what does it matter.' Then they took the Gays and again for most people it did not matter. When they came to take the Jews away there was nobody left to protest. People asked 'How could this happen?' But it didn't happen over night. It was gradual."

When the Nazis were defeated they were replaced by the Communists of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. "We swapped one dictatorship for another," he recalled. "The Communists had their own insanities." Especially just who was entitled to an education in schools with not enough seats? There was an order to which students were eligible. In the first category were the children of peasants and blue collar workers. In the second class were the children of intellectuals which was not so good because they had worked for the former regime. In the third category were the children of the bourgeois and clergy which included me. If there were 100 seats in the high school classroom only five to ten were available for the third category. My brother, who is smarter than me, did not get to go to high school. I managed to squeeze through and barely made it to college. There I studied to be a 'cheese technologist.' Actually I like cheese but for three years I studied the theory of how to make cheese."

At this tale of "cheese" he burst out in great laughter but at the time it was hardly very funny. He came to America in 1964 at the age of 22. After an undergraduate degree at City College of New York by 1975 he earned a doctorate from New York University.

Like many immigrants he had worked by day and attended night school. It was a part of what he describes as the "American Experience…Ten years after arriving here with nothing but the clothes on my back I earned a Ph.D." This led to a successful career in research that he surely might have continued to pursue. "That lifestyle was too narrow," he said. "I had a great interest in aesthetics.

"My interest in art goes back to Romania. I discovered art and modernism when I was just eighteen. It was literally 'The Shock of the New.' It shook every fiber in my body. I had a pre teen interest in art as far back as I can remember. What I was exposed to was Classic art and the art under Communism. There was no modern art as that was considered subversive crazy stuff. If people got interested in modernism the next thing they would want to overthrow the government. So they did a good job of suppressing all that. When I was eighteen I was attracted to a girl who was going to art school. I asked to see what she was doing but she was shy and didn't want to show me. I insisted and reluctantly she opened her sketch pad for just a moment. She briefly showed me a drawing of a landscape in a manner inspired by Cezanne that just astonished me. That was 45 years ago and I can still remember that brief moment. I had grown up looking at very conservative art and this was something different. It was an instant seduction. I have never been the same since. It changed my life. I became hungry to seek out books anything I could get my hands on."

When the family made it out of Romania at first they arrived in Rome. He haunted book stores and with what little money he had bought large format, cheap books with color plates of Picasso and other artists. There wasn't much modern art to see in Rome but he recalls encountering original works by Lucio Fontana the Arte Povera Sculptor and Painter (1899-1968). At the time the punctures and slashes in the canvas struck him as the ultimate act of freedom. The day after meeting with Stefan I spent several hours thinking about that while visiting a retrospective of Fontana at the Guggenheim Museum.

Arriving in New York he went immediately to the Museum of Modern Art where he spent days and then weeks. He discovered that if you purchased tickets for the movies you could stay after hours when the museum closes.

At first it struck him as unjust that not only did the museum own Picassos after Picassos but virtually all of the great masterpieces of modernism. It just didn't seem right that the museum was able to horde all that great work. "They had it all and I just sucked it up," he said. There was a drive to just devour art. That prevails to this day.

When he first maintained a gallery in New York for a period of time he set aside 12:30 to 2 PM once a week to see the portfolios of artists. "They lined up and I would take a look," he said. "The meetings were brief not more than about five minutes. If there was something of interest I would say come back later when the gallery closes for the day and I will take a longer look. In a day I would see an average of 20 to 25 artists. Over the years in that manner I saw perhaps 5,000 artists. In that process I found one great artist, Holt Quentel (she later dropped out and has disappeared. He asked if I knew how to get in touch with her). Not much came of it but it was worth it for me. I would rather see bad art than no art at all. I spent an enormous time looking at good art and an enormous time looking at bad art. I trained my eye looking at the best and the worst. So today it takes just a second to make up my mind when I look at new work. It is how I developed as a connoisseur. I never studied art history."

In the beginning it wasn't so easy to tell right from wrong. There was that first year of running a gallery in partnership with Donnelly when nothing happened. “We started on Newbury Street in December of 1980 and by June I was ready to give up," he said. "He was pretty burned out and his wife who was mostly supporting his end of the gallery pulled the plug. We made our first sale in December of 1981 literally one year after we opened. Eventually we caught on and became the hottest gallery in Boston."

In addition to the Starns and Anderson, as well as his wife Gina Fidel, the gallery represented the best of Boston at the time: Gerry Bergstein, Alex Grey and his wife Allison, Paul Laffoley, Louis Rissoli, Harvey Low Simons, Bob Lewis, Ralph Helmick, Roger Kizik, Paul Oberst, Susan Morrison, Jo Sandman, Jeffrey Schiff, Jod Lourie, Morgan Bulkeley, Randolfo Rocha, and Suzanne Higgins (Vincent). In 1986, Stefan and Linda opened in Soho and for a time maintained spaces in New York and Boston and tried to introduce the Boston stable to New York but "It was a different kettle of fish."

There was another period of transition with few sales in New York and rapidly diminishing resources. The decision was made to close the Boston gallery and of the original group only the Starn Twins caught on in New York. Eventually they left Stux to join the Leo Castelli Gallery. By 1988, at the height of the market, the gallery was listed in the "Year's Best" in the New York Times. There were strong sales to the Rubell and Saatchi collections as well as Eugene and Barbara Schwartz. But also the high stakes and overhead with a staff of twenty that it takes to maintain a position in the elite of the New York art world. The bubble burst and the gallery closed with a couple of years of dealing privately.

Those were dark days but by 1996 the gallery opened again in greatly reduced space as one of the first to move to the every growing scene in Chelsea. Several years ago he "discovered" his "very gifted" partner Andrea Schnabl. A couple of years ago I visited Chelsea and dropped in while they were in the process of renovating the current street level space. Last week, as we met and reviewed his remarkable personal and professional story, Stefan and Andrea seem to be on the top of their game. Together they are writing a new chapter in the history of Stux Gallery. Stefan has fought long odds to get where he is today. Truly he has few peers. He understands the precious gift of life and has made the most of it. Up and down, through good times and bad, it has been an inspiration to know him.