Mengelberg and Mahler by Daniel Klein

Robert Lohbauer in World Premiere at Shakespeare & Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 14, 2010

Mengelberg and Mahler

By Daniel Klein

Featuring Robert Lohbauer

Directed by Emile Fallaux

Set and Costume by Govane Lohbauer

Lighting Designer Stephen Ball

Sound Designer Michael Pfeiffer

Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre

Shakespeare & Company

June 11 to September 10, 2010

Runs 85 minutes without intermission

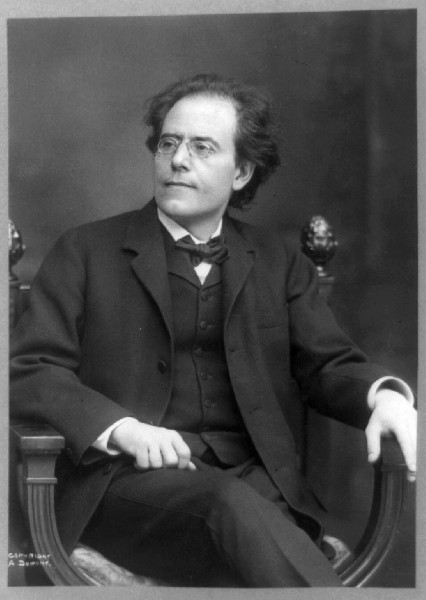

Joseph Willem Mengelberg (March 28, 1871 to March 21, 1951) was the fourth of fifteen children of German born Dutch citizens. From 1895 to 1945 he was the conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. In 1902 he befriended Gustav Mahler (July 7, 1860 – May 18, 1911).

During the decades that followed Mengelberg and his orchestra were renowned for presenting the works of Mahler. This continued, but became ever more difficult, during the period of Nazi occupation of Holland. In order to keep making music he made concessions to the Nazis including dismissing a number of his Jewish musicians. He considered them to be the heart and soul of his orchestra.

After the war, because of this perceived collaboration, he was stripped of his position, honors, and, by 1949, pension. Through appeals it was decreed that he may return to the orchestra after a term of five years in exile. He died in Switzerland at the age of 79 before the sentence expired. During this period he made no appearances or recordings.

From 1922 to 1928 Mengelberg was the music director of the New York Philharmonic. Starting in 1928 he shared the podium with Arturo Toscanini. They developed artistic differences and became lifelong rivals.

The ambitious but flawed one person play Mengelberg and Mahler, which is having its world premiere at Shakespeare and Company, focuses on the conductor in exile. The project has a strong Berkshire locus in the writing of Daniel Klein. He enlisted a member of S&Co, Robert Lohbauer, to take on a difficult and demanding role. The director, Emile Fallaux, previously collaborated with Klein on the screenplay The Titan from which this stage production is derived.

The play will resonate with audience members in accordance with what special interests they bring to the performance. It is best to start with knowledge and passion for the music of Mahler. We hear excerpts of a number of the works with the actor at intervals conducting to the music heard on a phonograph. There are also projections of vintage film clips of the conductor and his performers.

We are asked to accept his arguments of innocence regarding alleged collaboration. He rails against the harshness of the heartless imbeciles who have forced him into exile. If soldiers of the Third Reich argued that “I was just taking orders” the mantra of Mengelberg was the equivalent of “I was just making music.” In his emotional interpretation he was easing the soul and spirit of the occupied Dutch people. He was also dedicated to preserving his orchestra.

While his rival Toscanini refused to perform for the Fascists in Italy or the Nazis in Germany he did so from the podium in New York. With bitterness Mengelberg informs us that Herbert von Karajan and Wilhelm Furtwängler, among others, conducted in Nazi Germany with no consequences to their post war careers. Mengelberg argues that he struggled to continue to present Mahler during the war. His works were also conducted by an all Jewish Dutch orchestra. There is a scene when Mangelberg attempted to attend such a concert but was turned away as a gentile. It is assumed that the orchestra subsequently perished. As was the fate of the Jewish musicians in his orchestra.

The Nazis did not approve of Mahler. Largely for social and political reasons he converted to Christianity. In an amusing moment during a grim evening of theatre Mengelberg quips that “Mahler as a Christian is like Confucius as a Jew.”

Long before the war Mengelberg was devoted to German music. He had little or no interest in Dutch composers. In one scene he heaps scorn on Debussy and the “circus music” of Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faun. He appears to be oblivious to the fact that during the war his orchestra presented primarily German composers. That this might be perceived as politically incorrect escapes him.

While experiencing this performance there may be reasonable doubt regarding the protests of innocence of the exiled conductor. This intellectual misgiving was exacerbated by the labored and uncompelling performance by Lohbauer.

The actor is advanced in years. He is about the same age as Mengelberg in exile to whom he bears a physical resemblance. Lohbauer is out of shape and struggled with the stamina required by the role. There were times when he appeared to be out of breath. This impacted his ability to create an emotional arc. There was little range as he shifted from the sublime reverie of the music, to rage against his tormentors, and jealousy of rivals. While a disciplined and gifted actor he is not up to the demands of the role.

The director, Emile Fallaux, did not serve him well in this effort. At one point Lohbauer prepares for bed and strips down to an undershirt, pants with suspenders, and bare feet. It is an allegory of being stripped of his dignity and humbled. If clothes make the man then his decision was a move in the wrong direction. It did not evoke the empathy that was intended. Or even much sympathy. It just made one anticipate the end of an evening that was beyond salvation.

There were many in the audience who accorded the actor a standing ovation. With this production in particular it is a matter of what you brought to the theatre. Undoubtedly this new play will find an audience. Caveat emptor.