Berlin's Jewish Museum By Daniel Libeskind

A Flawed Museum in A Deconstructivist Masterwork

By: Mark Favermann - Jun 15, 2009

Berlin is a unique city of many parts. It is one part 18th Century Colonial Williamsburg with its recreated and sometimes restored old buildings and several parts mid and late 20th Century dark history with its reused Nazi Buildings and no frills East German Stalinest Soviet style structures. A third part creates the city as a wonderland of 21st Century contemporary mega-structures. Sprinkled inbetween are buildings from various decades reflecting the architectural heritage of a grand city.

Today, Berlin is the most contemporary looking European city. Renovating, building and changing, Berlin's last hundred years, for good or bad, demonstrates a broad spectrum of aesthetic innovations as well as architectural dead-ends. The major architectural names echo through design history: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Lord Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and scores of others. Following the turn of the last century, through to the present day, it seems each architectural or stylistic movement was showcased there.

From AEG's radical industrial buildings at the beginning of the 20th Century, to Peter Behren's influential structures and product designs, to Gropius' Bauhaus and the almost ubiquitous mid-century International Style fostered by van der Rohe, Berlin has been a center of stylistic expression. In this long and sometimes distinguished tradition of Modernism and contemporary design, Daniel Libeskind's Decontructivist Jewish Museum of Berlin is one of these seminal if not iconic pieces of architecture.

Deconstructivism was one of the "isms" of the 20th Century. Along with Modernism, Post Modernism, Brutalism, this style loosely referred to a sensibility vaguely connected to the constructivist art of the second two decades of the 20th Century. It was especially expressed by the Russian (Soviet) avant-garde of the 1920's without the politics. It is even less connected with the French philosopher Jacques Derrida's method of inquiry rather than a philosophy.

This Deconstructivist methodology was applied to the study of both linguistics and literature. Derrida's approach was in reaction to what he felt were the idealistic and thus, less rigorous methods of inquiry established during the Enlightment. With this said, other academics, especially Mark Wigley who was an architectural historian and lecturer at Princeton, attempted to apply deconstructive thought to architecture. This somehow had an academic resonance. In fact, Dr. Wigley's dissertation at University of Auckland, New Zealand was entitled "The Deconstructive Possibilities of Architectural Discourse." Rightly or wrongly, Wigley made a case for an architectural deconstructivism.

In 1988, the highly establishment then eighty-something architect, and former director of the Department of Architecture and Design at Museum of Modern Art, Philip Johnson, and Mark Wigley put together an exhibition at MoMA of a rather disparate group of architects entitled Deconstructivist Architecture. Included in the exhibit were Bernard Tschumi, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaus, Coop Himmelblau, Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry and Daniel Libeskind.

They supposedly were applying this deconstructivist approach and principles to their architecture. At that time, Tschumi, Koolhaus, Eisenman and Libeskind had actually written much more about architecture than they had ever built. All were considered academic or paper architects.

I actually visited and reviewed the 1988 MoMA show. Cramped into a small space on the top floor of the museum, there were geometrically imposing drawings, renderings and elegant sculptural scale models with a minimum of explanation and simple labels. Perhaps, curator Johnson was trying to present architecture as art? Or, arguably, it was just a thin exhibit? I found it rather inside baseball in its approach. The show assumed that anyone viewing it would get it. The exhibit was provocative, had a few reviews and articles touting it and faded away as an architectural and museum footnote. Yet, over 20 years later, there are lingering aspects of the designs.

At the time, the work exhibited was referred to as a new sensibility that was obsessed with strategic twists, warped planes and folded lines. The catalogue for the show actually stated that traditional design with its virtues of visual unity, harmony and clarity were being replaced by fracturing, disharmony and even mystery. The often provocative Johnson was quoted as saying that the works displayed a collective notion of the pleasure of unease.

The catalogue further suggested that deconstructivist architecture recognized the imperfectability of our civilization. In other words, counter to the optimistic utopian approach of the Bauhaus, Le Corbusier, and Wright, Deconstructive architectural design is in reaction to and an underscoring of the chaos and instability of contemporary life. This was/is an architecture of angst, a design of agita and a view of the inside of a tornado. The lines, angles and twists are diagrams of the human condition and our contemporary time of risk and potential real consequences. However, this underpinning philosophical view has given way to a pure aesthetic view. Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin may be the best example in the world of a major Deconstructivist building.

In the years since the exhibit all of the architects included in the show have become or remained star architects. By the way, though Frank Gehry was pleased to display his work at MoMA, he was and is not happy to be labeled as a Deconstructivist architect. This is similar to the 1932 MoMA Modern Architecture show, also co-curated by Philip Johnson, where Frank Lloyd Wright said that he was not part of the other exhibitors' aesthetic.

The elimination of the Berlin Wall in late 1989 opened the city to the architectural exploration and development that are its hallmarks today. Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin was one of the first major designs commissioned following the fall of the Iron Curtin. This came about because Daniel Libeskind won an international competition in 1989 against 165 competitors.

Initially the design was to be only an extension of the existing baroque Berlin Museum to accommodate the Jewish department. But after several years of discussion,debate and the sheer force and energy of Libeskind's design, it was decided that the whole building, both old and new in its entirety, be dedicated as a Jewish museum. His mega-persuasive abilities added to the swaying of civic opinion as well. The building was completed in 1999; the museum opened to the public in 2001.

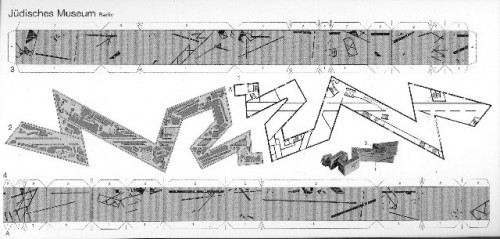

Architect Libeskind's design was quite startling. He set his irregular zigzag building next to the former appeals court building in complete contrast to the existing structure. The designer created a monolithic structure clad in zinc sheeting. The structure's shining silver facade will eventually patinate over time. Its slit windows are designed to suggest scratches, wounds and scars. Included in the four stories are three for exhibition and one for administration.

Libeskind's building is entered below ground from the older structure. There are three intersecting paths. The architect designated the first one as an "axis of historical continuity." The second path leads into the E.T.A. Hoffmann Garden with its slanting pillars that are symbolically denoting exile. The third comes to a deadend inside a bare concrete tower with no exit.

The zigzag form that defines the Jewish Museum's structure is pierced by a straight line. This line cuts through concrete shafts in the building. These spaces are partially inaccessible and linked by bridges. According to the architect, these symbolize the void which the extermination of Jewish life in Berlin has left.

And Libeskind justified the void by relating it to a specific historic event. The architect described four factors contributing to the design of this structure. The first was linking between Jewish tradition and German culture. This concept produced the deconstructed Star of David which gave the literal alignment of the building. The second element, and one rather difficult to actually understand, was that Libeskind tried to complete, using architecture as a medium, the incomplete opera by Arnold Schonberg, "Moses and Aron." The opera ends with the phrase, "Oh word, thou word that eludes me."

With this all said, the interior of the museum is confused and often difficult to navigate. This situation is made even less user friendly by often uninspired and rather dreary exhibit vignettes and settings. How much the architect had to say about the displays is questionable, but his form clearly often dictated the functioning of the interior space.

The third factor that the void symbolizes is the literal, spiritual and intellectual murdered, missing or deported citizens of Berlin. The fourth is based upon the essay by Walter Benjamin, the Berlin born Jewish critic and philosopher (1892-1940), "One-way Street." Benjamin used architecture and urban structures as themes and metaphors throughout his essays. The practitioners of Deconstructivist architecture employ a great deal of symbolism and conceptual description as well. With his decades long background of university teaching and writing, Libeskind is a master at this.

Daniel Libeskind was born in Lodz, Poland in 1946. His parents were Holocaust survivors. The family emigrated to Israel in 1957. Three years later the family moved to New York. He has been an American citizen since 1965. At first it was thought that he would become a concert pianist, but he later decided to become an architect. Libeskind attended Cooper Union School in New York City and then the University of Essex for his master's in the Theory of Architecture. He immediately went into academia. Perhaps, among the most notable was his tenure as the Dean of Architecture at Cranbrook Academy in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Subsequently, he has held appointments at major universities throughout North America and Europe. Libeskind's work is often considered daring and not accessible. To sell his building designs, he is known to skillfully work local politics and the press to make his aesthetic case.

Though he has a number of smaller residential projects in his portfolio, Libeskind is now recognized primarily for a number of completed and ongoing museum projects. Besides the Jewish Museum in Berlin, his designs include the extension to the Denver Museum, The Imperial War Museum North outside of Manchester, UK, an addition to Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada, the contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco and the Danish Jewish Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark. There is even a Libeskind design for a new museum in Boston, The Center for Arts and Culture, to be located in the Kennedy Greenway that went on hold because of the recent financial crisis and eventually was abadoned. Few of these works present the design sophistication and clear strength of visual resolution of Berlin's Jewish Museum.

In February 2003, Libeskind won the competition to be the master plan architect for the reconstruction of the World Trade Center in Manhattan. This has developed into the controversial Ground Zero quagmire that has become tied up in politics, governmental inertia, developer greed and architectural egos. Libeskind's original plan is now marginally connected to the project. Even Daniel Libeskind's great persuasive gifts of writing and speaking were not enough to underscore his Ground Zero vision. This appears to be a lost design cause.

Speaking of vision, it is a shame that little creative vision was given to the actual exhibits of Berlin's Jewish Museum. If the museum structure is a compelling masterwork, the museum exhibitions themselves are a dull, disjointed series of vignettes and mediocre installations. This is history as incident, history as guilt, and history as events rather than a history of longevity and even social evolution. Jews have lived in Germany since at least the 4th Century.

The Jewish Museum portrays Jews as "visitors" to the country not as an involved and evolved minority that has impacted the German culture and people along the way. Heinous Anti-Semitism has arisen at various times over the 17 centuries of residence by Germany's Jewish citizens. This was also true in most European states over the years as well. Clearly, the most grievous harm was done by the Nazis in the 1930s and '40s.

Yet, as terrible and woeful as that was, there must have been times of peaceful and secure longevity by the Jews of Germany. Little of this is shown. Selected prominent Jews from all walks of life are singled out, but the day to day existence of the vast majority of Jewish Germans is given short shrift. They were probably very similar to most non-Jewish Germans. Certainly at times, there would have been joyful times in the Jewish German community? Yet, Berlin's Jewish Museum seems to pare down the quality of life of Jewish Germans prior to the Nazi era. This dissatisfaction with the exhibitions' content and presentation is a reaction of thoughtful Jewish and non-Jewish visitors to the museum alike.

Like the great composer Felix Mendelssohn, other Jews of Germany must have made great and perhaps not so great music and art along the way. This museum has no music, little art. It is a very flawed if not a failed exhibition space. Its content is often less than scintillating and presented in odd, often incomprehensible ways. The exhibits wind, twist and turn with the building's structure instead of being a counterpoint to it. The displays are often disjointed and unclear. Questions like what century, what period, and how did that fit into the German experience are never fully answered or often asked. There is no joy, no celebration of life in the museum. Guilt is fine if it is balanced with thoughtful understanding. In this case, this would be a truer recognition and even acts of redemption. Unfortunately, here was a major opportunity lost.

Of course there are many critics of Deconstructivist architecture. These individuals find it only a formal exercise with little social significance or resonance. Others, such as architectural historian Kenneth Frampton, feel that it is elitest and quite detached. Even so, the Jewish Museum Berlin by Daniel Libeskind is a masterwork if not a masterpiece. There does seem to be a sculptured social and cultural reverberation to the place. The abstract tools that the architect employs craft a symbolic even metaphorical design. This building is style as structure. However, the museum is physically compelling yet intellectually boring. Another and perhaps major architectural issue is that Berlin's Jewish Museum may be the best design work that this architect has ever done or will ever do.