The Painted Life of Gregory Gillespie

Directed by Evan Goodchild

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 15, 2025

The Painted Life of Gregory Gillespie

Directed by Evan Goodchild

Cannes International Film Week Festival

May 12 through May 31, 2025

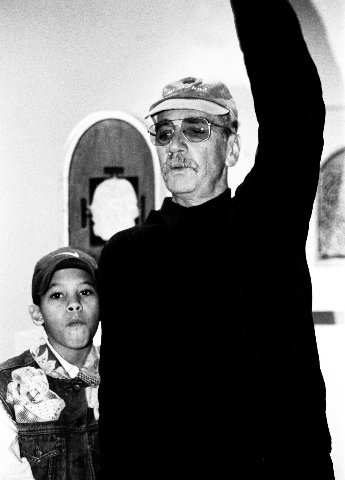

The film is executive produced by Eric Brecher and produced by Rick Segal and Robert Kohler, documentary filmmaker and producer, Lawrence Hott of Florentine Films, is the lead production consultant. Christopher Thomas Wood is the film’s writer. The feature length film is entered in numerous festivals.

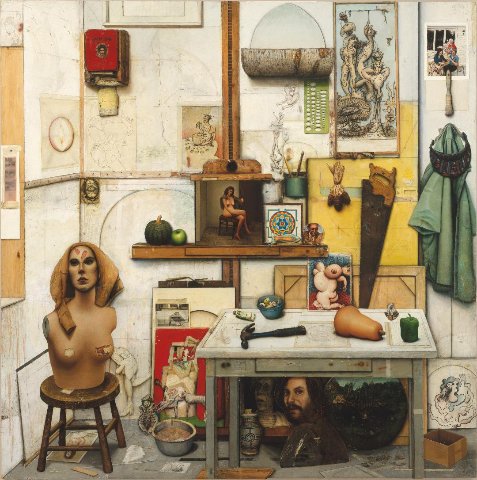

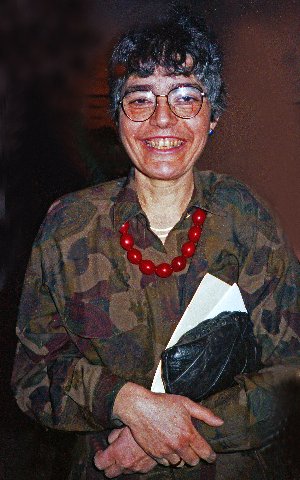

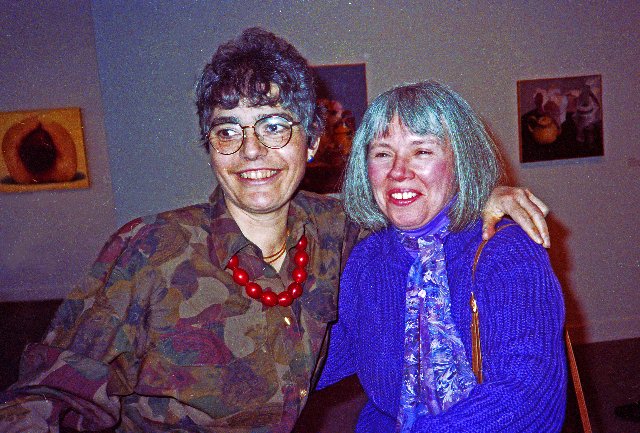

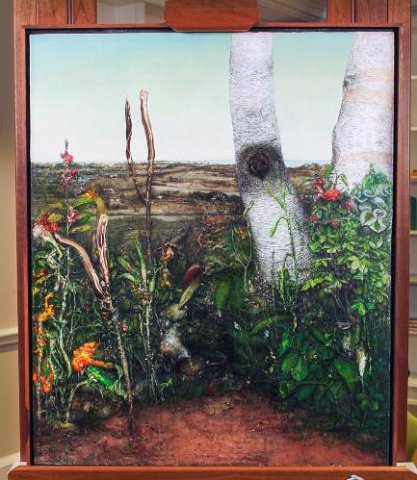

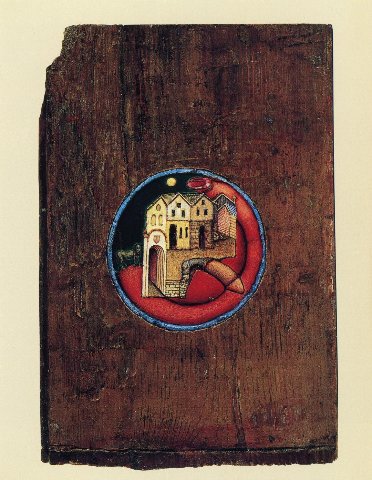

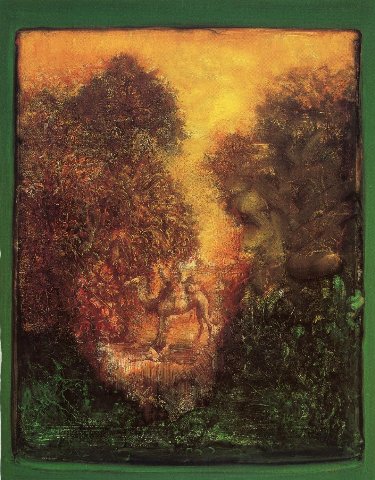

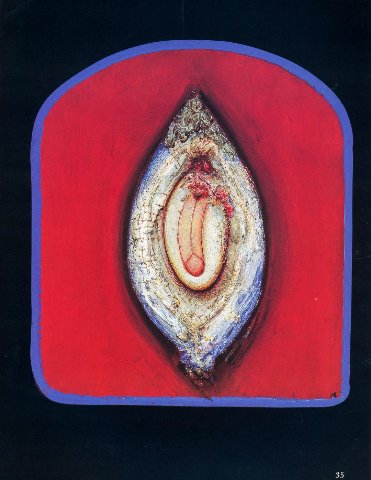

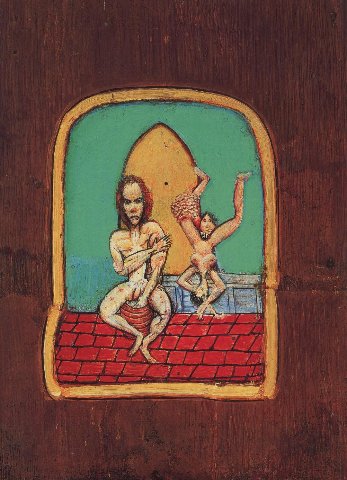

While representational and narrative the work of Gregory Gillespie (1936-2000) defies categorization. There is obsessive rendering and meticulous brushwork but unlike others of his generation such as best friend and antagonist, William Beckman (born 1942), he was not a realist. That term better describes the work of his first wife, Frances Cohen Gillespie (1939-1998). They worked side-by-side for many years. While she rendered what she observed he explored visionary fantasies including the erotic, horrific and Tantric. Working with collage and assemblage he created shrines including a tomb intended for his ashes.

At the height of his career, in the 1980s, the work sold well and he was widely viewed as one of the unique masters of his generation. Sales and critical attention slipped in his last five years. This well crafted and insightful documentary film spearheads an effort to revive his diminished status.

In a New York Times obituary Roberta Smith acknowledged his inclusion in several biennials of the Whitney Museum of American art but stated that “he remained an art world outsider, respected by many but enthusiastically embraced by few.”

In a summary of his work Smith stated that “His art was known for an obsessive attention to realistic detail, but the term realist fit only a narrow swath of his sensibility. He once told an interviewer that he was seeking a reality ‘beyond our sense,' and he pursued it with a variety of artistic styles, techniques and references. He mixed his realism with Expressionist distortion and Surrealistic juxtaposition, just as he supplemented his meticulously applied oil paint with roiling brushwork, photomontage, collage, assemblage, thickly built-up surfaces and, recently, photocopied images.”

There was a dark side to his life and work. When he was five, his mother was institutionalized while his father was a functional alcoholic who never missed a day of work. In a devoutly Roman Catholic family he and a sister were largely raised by an aunt and uncle. When they moved to California, in the film, Gillespie’s older sister, Alice Bonavita, states that she largely took over the role of parenting. She also revealed a fantasy of murdering their father.

At a young age he was taken on by Bella Fishko director of Forum Gallery. He was in Florence with a Fulbright/ Hays fellowship in 1966 when his first one-man-show sold out creating a waiting list for work. They remained several more years in Italy with a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. He studied the masters from Masaccio through Mantegna and Carlo Crivelli. The work was inventive, eccentric and never academic or attempted to recreate the manner of the Renaissance.

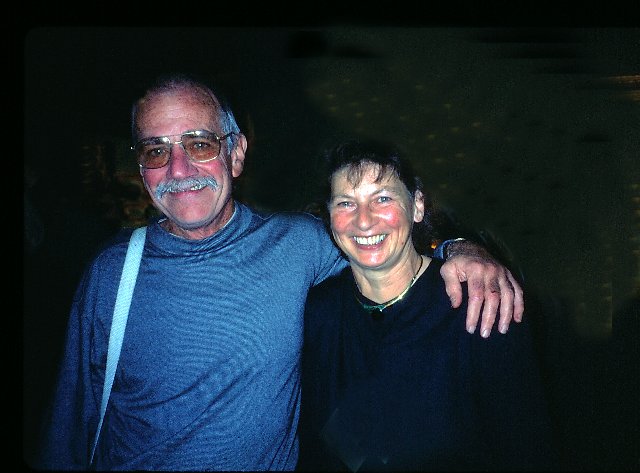

By the time they returned in 1970 they had a son Vincent and then a daughter Lydia. Mothering disrupted her career as an artist. With the children grown Fran was back on track but taking years to complete a work; as I found out when including her in a traveling show of portraits. When we were putting together the catalog for several weeks she sent me updated images. I could see no significant differences.

Gregory’s work was successful and Fishko advanced money with accounts settled after exhibitions. That changes when Bella retired and the new work, which was looser and more visionary, received tepid reviews and poor sales. Taking over for his mother Robert Fishko was less inclined to maintain the status quo. There were slim prospects of overcoming a significant debt to the gallery.

The artist was described by friends as having issues including depression. He was no longer interested in creating the large self portraits, still life, and composite works that were sought by collectors. He had moved on and was inventing a new style which too few understood and appreciated.

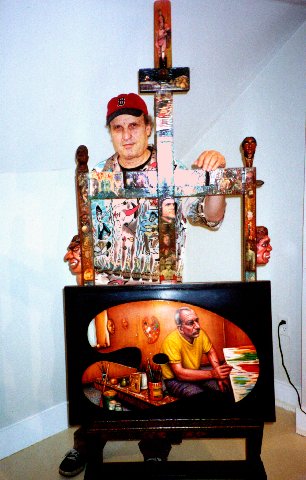

In the last years Nina Nielsen of Boston showed the new work. That included displaying his “Tomb” a painted, multi-media sculpture intended to contain his ashes. I discussed it with him in the gallery with his adolescent daughter, Jay, who expressed misgivings about the work. In light of what soon followed it made one wonder if this was a whimsical riff on death with gallows humor or entropy toward a darkening mood. Was it a cry for help and intervention?

I discussed with Nielsen the possibility of my curating an exhibition of the late, unpopular, looser, expressionistic visionary paintings. The project would have presented the complex work in an academic rather than commercial setting. It never happened.

On April 26, 2000 his second wife Peggy found him hanging in the studio in Belchertown, Mass. At 63 he died relatively young.

Knowing the tragic end of his life it is difficult to view the documentary film in terms other than clues leading to that shocking conclusion. The film does not provide a deep analysis of what went wrong. As the director, Evan Goodchild, told me he sidestepped a “lot of landmines” in order for the film to get done. Significantly, there are works for sale here and there but no gallery represents the estate.

The work is well represented in museums. From his first show at Forum Gallery several works were acquired by Joseph Hirshhorn. In 1977 The Hirshorn Museum organized a traveling show of the work. In the film, former director Adam Weinberg, relates that the Whitney Museum showed the work which was also included in several Whitney Biennials.

When Amy Lighthill was adjunct curator for contemporary art at the Museum of Fine Arts she was instrumental in acquiring “Imaginary Pregnancy” a nude study of his wife Peggy. She was interested in the Northampton Realists as was curator of American art, Ted Stebbins who she reported to. The MFA acquired major works by Scott Prior, Jane Lund and Randall Deihl as well as Fran Gillespie. When Stebbins later left for the Fogg Art Museum he organized a show “Life as Art: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie and Frances Cohen Gillespie” (December 6, 2003–March 28, 2004.)

Harvard PR stated that “This exhibition surveys the work of two of the most iconoclastic realist painters at work in the United States during the late 20th century. Both studied in Italy and were influenced by the technique of German and Flemish Renaissance masters, yet both also deeply identified with the passion and commitment of Jackson Pollock and other members of the New York school of the 1950s. Gregory Gillespie became well known for his probing self-portraits and his sexually charged paintings of fruit and vegetables. Frances Cohen Gillespie worked in a more tortured style, producing only one or two large-scale floral compositions annually. The two painters, married from 1959 to 1983 and much admired by other artists, died at the height of their careers, Frances of cancer in 1998 and Gregory by suicide two years later.”

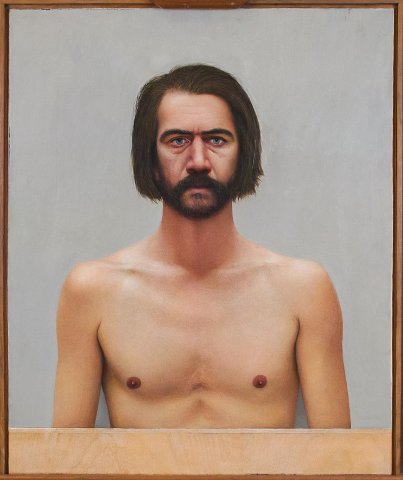

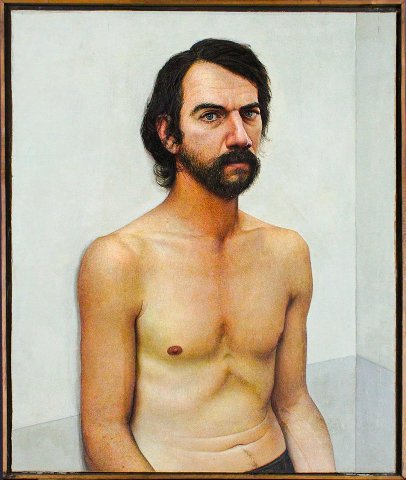

Many believe that Greg was one of the major American masters of his generation. That opinion is affirmed by many artists, curators, writers and collectors who testify in this compelling film. There is so much detail that I viewed it twice. Goodchild unearthed images of many early works that I was unfamiliar with. A number of the late self portraits reveal a level of anguish conveying the torment of his state of mind. The interviewer asks “Why do you feel like shit today?” There is a self-conscious reaction but he responds evasively. Prior to his death, we learn from a friend who dined with him that he hadn’t slept for several days.

He made his own way and developed a unique style and viewpoint. During three years at Cooper Union he deflected the concepts of his abstract expressionist teachers. While other students used broad strokes with charcoal on paper he executed meticulous studies with sharp pencils. There are tantalizing glimpses of dark paintings he was executing at the time. Completing a master’s degree at the San Francisco Art Institute there is slim indication of what he learned. It is intriguing to consider that he interacted with Bay Area Figure Painting. This is a worthy subject for research.

In Rome he created the Trattoria paintings. Typically, they were atmospheric interiors with views of monuments seen through windows. There are a number of images of women seen from the rear walking away. It’s speculated that they represented his mother who left him at an early age. There is a theory that children abandoned by parents feel flayed and exposed. We glimpse a couple of grim works with that theme. They reminded me of works by Hyman Bloom as did his anthropomorphic still-lifes of gourds and turban squash.

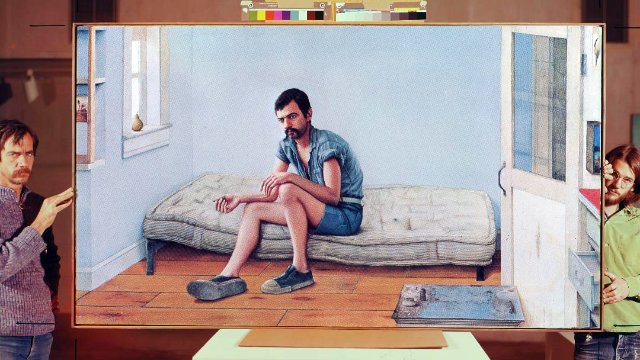

A dominant impression of the work is the proliferation of self portraits. Initially, they are stoic and hide the feeling of the sitter. We read them for their visors, undershirts and occasional squalor. The image of him awkwardly sitting on a grungy old mattress visually reeks. The clutter of the studio gets into the paintings either as rendered, collaged snap-shots or objects. Toward the end he painted sinks, toilets, and telephones or trash barrels. Whole swaths of the studio became works of art. Is this a clue that he was losing it?

The banter and rivalry with William Beckman is particularly revealing. They painted portraits of each other in the manner and style of their sitters. Beckman speculated as to how Gillespie’s work will hold up in the future. Which is now. Gillespie reflects on all those who tell him that he’s a great artist. About which he was skeptical. Only time will tell.

There are conflicting emotions that surround memory of this artist. We feel anger and frustration toward those who end their lives. The film documents friends who expressed shock and anger. How could he abandon those who loved him? The film raises the question but provides no answer.