Jeffrey Gibson: Native New Yorker

Fancy Dancing

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 16, 2013

Jeffrey Gibson: Native New Yorker

Fancy Dancing

Published in Maverick Arts 06/06/06

Right now there is a lot on the plate of the painter/sculptor Jeffrey Gibson. At the time of the recent studio visit in Brooklyn works were partly crated in preparation for a move just a couple of blocks away. By the end of August he is scheduled to install a relief sculpture, the largest and most ambitious of his career, for a group show “No Reservations” combining native and non native artists, curated by Richard Klein for the Aldrich Museum of Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut. There is a solo show on tap for Samson Projects in Boston this fall. He will be in a group exhibition in March 2007 "Off the Map: Landscape in the Native Imagination" with James Lavadour, Emmi Whitehore and Carlos Jacanamijoy, and an essay by Paul Chaat Smith, curated by Kathleen Ash Milby, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in lower Manhattan. He is also scheduled to participate, this Fall, in group shows at the Westport Arts Center, in Connecticut, The Peekskill Project in New York, “Paumanok-a” for SUNY, Stonybrook, NY and “Tropicalism” at the Jersey City Museum. In addition, Samson Projects will continue to present works by Gibson in its grinding itinerary of national and international art fairs.

The school year is over at Cooper Union where he has been an adjunct faculty member in the Outreach Program since 2004. So he is able to work full time in the new studio keeping up with all those commitments and deadlines. It would appear to be the price of success but Jeffrey seemed tense as he clutched a large cup of coffee. Since there was little evidence of new work I asked how he planned to meet the now looming Aldrich deadline for which the curator negotiated the donation of a significant amount of the silicone material for the project from a Connecticut based company. When asked how it was progressing he responded that it will get done, it always does. One measure of the success of this relatively young artist, who earned a Masters of Arts degree from London’s Royal College of Art in 1998, is that sales of art represent about half of his annual income.

Clearly, there is a strong support system for this artist who demonstrates great potential but that also equates to enormous pressure. Particularly, as is the case with young artists, when the work is in the midst of dramatic change and transition. In the glare of the klieg lights it is tough to experiment and make the mistakes which are a normal part of growth and progress. Particularly, when the work is veering off in several directions from painting through sculpture and in between. To my eye it doesn’t always work and I didn’t hesitate to discuss critical issues with him. It’s what critics do. If they are truly critics and not just art writers. It gets messy.

My interest in the artist and commitment to the work, long term, ratcheted up when I attended his presentation during a remarkable Native panel during the College Art Association annual meeting in Boston this past Spring. It was compelling to learn and appreciate how dramatically the work had evolved during a relatively short interval of time. But there are also a daunting number of issues and differences: Generational, sexual, racial, cultural, that define and shape the work but are also very different from my own sensibility and life experience. It is important to recognize and concede differences and, if you respect the artist and work, struggle to engage and resolve them. Arguably, such a dialogue may represent a growth curve for both artist and critic. So there we were attempting to negotiate a tough and complex dialogue particularly given Gibson’s multi-valent influences. Like raves and ecstasy, or pow wows and fancy dancing, as opposed to acid and Woodstock for my generation. One would think there was a commonality but not really.

We started with the primary theme of my ongoing research project; the balance of art and identity among contemporary Native American artists. “Personally, I grew up with ambivalence about being native,” he said. “It was a generational response. There was a sense of shame. We were given few models of successful individuals that included being native. For me being native is an idea of spirituality. My father is Mississippi Choctaw and my mother is Oklahoma Cherokee.”

The artist, who was born in 1972 in Colorado Springs is the son of a civil engineer who worked with the military. The family moved a lot including time in Europe. “When I first started to engage (with Native culture),” he said. “I was regarded as a city kid. I was close to my aunts and grandmother. As an adult in my 20s I was more engaged. When I was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago I worked part time at the Field Museum (where he had direct contact with its great Native collection).”

As the son of a successful engineer Gibson had a different access and relationship to education than someone growing up embedded in a traditional culture. “My father was the breakthrough,” he said. “He was one of ten brothers. My parents went to Indian boarding schools and my grand parents were sharecroppers in Mississippi. Both grandfathers had drinking problems that led them to (sobriety) and becoming Southern Baptist ministers. They were preaching to Indians in Choctaw and Cherokee. My father’s first language is Choctaw and my mother’s is Cherokee. My grandfather would preach in ten churches over ten hours on a single Sunday.”

With maturity he grew closer to his heritage. “The best of Choctaw culture is what I represent,” he said. “My tribe opened a casino about a dozen years ago. Our chief, for the past fifty years, Phillip Martin, hired the same developers who worked with casinos in Vegas and other places. He also built one of the top five golf courses in the country. Thirty years ago he had a plan to bring business to Mississippi. There was pragmatism and the impulse not to make of the Choctaw some romantic notion. It was about risk management. When the casino opened he hired an all white management staff. He realized that in Mississippi race is an issue.”

This pragmatism paid off and the business plan succeeded. Although the local press carried racists reports that the Indians were “drinking up the profits.” After earning a BFA in Chicago Gibson had the idealistic notion that he would teach art on the reservation. But he was stunned when he was turned down and informed that he might reapply when he earned a master’s degree. This actually led to the Chief seeing that he was funded for the three years in London at the Royal College of Art. The Chief, whom Gibson describes as a remarkable visionary and savvy businessman, informed him that he was worth more to the tribe when grant writing and making government reports, as a grad student in London, than teaching art on the reservation. He became an element of the success story of the Choctaws.

He describes having come to a point where he has tried to stop fighting himself; to overcome his “defeatism” and to “have a disregard for how people regard me as native.” Clearly that is daunting and he adds that “I want to respect the native community. I believe in being a hypocrite and making mistakes otherwise I could not move forward on a day to day basis. It is way too much work not to be myself and make the work I want to make. In terms of native culture I step slowly but I do not want to be compromised.”

So it has taken time and sweat equity to develop the work given such a range of restraints, inspiration, globalization, queer culture and other mandates. At the age of 34 he states that he has been making mature and serious work for a decade but only showing it for the past three years. Despite the level of critical and curatorial interest and sales he is still in the initial stages of building a professional career.

It was at this point that I interjected concerns reiterating some of the points covered in a review (Maverick Number 161) of his first two person show (with his spouse Rune Olsen) at Samson Projects in 2004. Camilo Alvarez, the director of Samson Projects which exclusively represents Gibson, was profiled in Maverick Number 171.

For both of us it was difficult to revisit that dialogue. He listened intently and patiently as I reiterated those arguments. It seems he has heard it all before so there was a comic irony as he bounced it back as a parody. He reeled off the litany “Too lush. Too crafted. Too objectified. Too, too, too, too, too. But to respond how? To please who? You? The art world? Would that be careerist? Is my goal is to end up with a gallery in Chelsea? That said, what I want to see is extremely personal.”

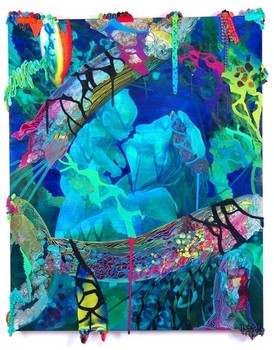

This seemed to break the ice as he engaged in the opportunity to take on direct criticism. He summarized how those terms and criticism are all too familiar and “comprise an analytical and critical statement against how persons of minority background with references to cultural objects in their work are referred to as ‘decorative.’ Did you ever attend a pow wow (no) or see a fancy dancer (no)? If you did you could understand. They (his paintings) relate to the whimsy objects of the 19th century which is what I talked about at CAA. To me the way that the figures are working are representation jammed up against pure abstraction. Up to now I have been very selfish in what I produce but I am more willing to consider other views.”

Thanks, I needed that. Looking back at the notes, now just hasty scribbles on a page, it is difficult to recover the intensity of the moment. It did not surprise me and it was helpful to get at the essence of the work in the artist’s own terms. Obviously there is risk involved in pushing a dialogue to that level. It can result in a breakdown as easily as a breakthrough. But I was not prepared for what came next. We groped back to the issue of spirituality in his native identity and how that gets embedded in the work. He had already described his ambivalence about growing up native. The catharsis occurred when he worked at the Field Museum surrounded by its daunting collection and the collective wammy of all those ghosts and ancestors.

Part of his work at the museum was to prepare objects when representatives of tribes came to examine and potentially reclaim sacred objects. He worked with a staff anthropologist and there were elaborate protocols to be observed. This resulted in being present during remarkable moments. As he started to describe such incidents he lost his composure. The power of the objects and memory of those seminal moments was overwhelming. He expressed how much he truly believed in the intensity of the objects and their spirituality.

He described how early on, while alone in the storage area of the museum, he just lay down on the floor surrendering to and truly not knowing just what those surrounding objects would say and do to him. It was the ultimate existential moment of coming to grips with the power of the past. I agreed and shared with him my own experiences of working for three years, as a young man, in the basement of the Egyptian collection of the Museum of Fine Art and making peace with the mummies that surrounded my work area.

A moment and experience such as this renders rather irrelevant the usual studio visit. Rarely does a stranger get such glimpses into the humanity and vulnerability of another human being. It brought to the foreground the entire issue of just what such crucial historical, cultural and spiritual objects, of any religion and people, are doing in the collections of museums. How, for example, does a medieval crucifix, or a Buddhist sculpture, become an object in a museum completely amputated from its original function and context?

“Some objects are stronger than me,” he said. “I’m not afraid to say this as it is the truth.” It will be intriguing to follow how that primal essence gets embedded into and grows with the work.

-----