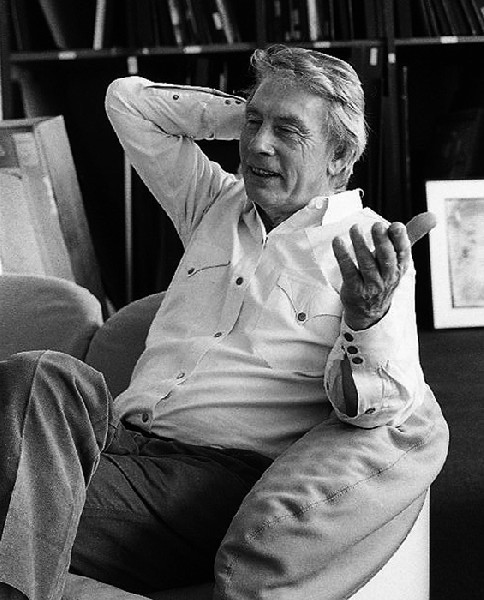

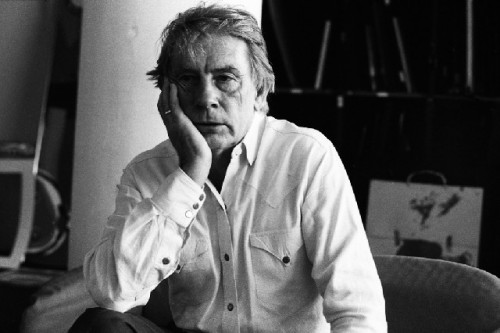

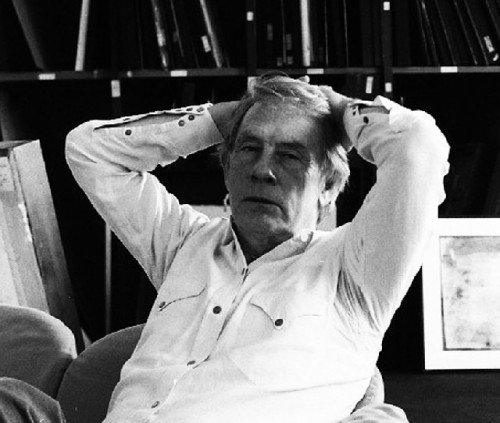

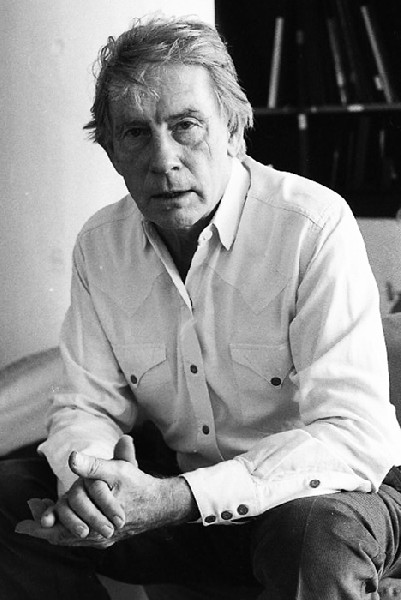

Lester Johnson 1919 to 2010

A Leading Figurative Expressionist

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 17, 2010

Lester Johnson (January 27, 1919 to May 30, 2010) was one of the leading exponents of Figurative Expressionism. The movement which included artists in New York, Provincetown, Chicago and San Francisco emerged in response to the non objective aspects of Abstract Expressionism. While it flourished during the late 1950s and early 1960s it coincided with and was overshadowed by Pop art.

There are many versions and interpretations of Figurative Expressionism. The lists appear to expand and contract with little or no consensus among curators and critics. Despite some key artists the movement is widely viewed as marginal. There has been some cherry picking as individual artists have been researched and shown. But cohesive study, exhibitions and publications remain unrealized. While there have been isolated exhibitions and catalogues they tend to further obfuscate a complex history.

In 1986 I was asked to write an essay on Johnson for a traveling exhibition organized by Paul A. Chew the director of the Westmoreland Museum of Art in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. The project was coordinated by Carl Hecker the director of the David Anderson Gallery. There were meetings in the warehouse of the gallery which was in essence the estate of art dealer Martha Jackson. She had represented Johnson as well as the African American artist Bob Thompson (1937-1966). It was Lester who urged Jackson to show Thompson’s work.

Over several months I met with Lester in New York and his Connecticut studio. In addition to researching his work we also discussed the “return of the figure,” the debates of the Artists’s Club in New York, and the exhibitions of the Sun Gallery in Provincetown.

Lester was frank and insightful in providing a narrative of his own development and relationship to peers. I came to conclude that he along with Jan Muller (1922-1958) and Thompson were the leading figurative expressionists of the Provincetown/ New York school. My research led to exploring parallel developments in San Francisco focused on David Park (1911-1960), Richard Diebenkorn (1922 to 1993), Nathan Oliveira (Born 1928) and Joan Brown (1938-1990). There were strong parallels to the early work of Leon Golub (1922-2004) in Chicago.

A major challenge entailed tracking the course of Figurative Expressionism as a tributary of Abstract Expressionism. Looking back at that era in the late 1950s and early 1960s it is important to consider the passion with which movements and their differences were discussed and debated. Reading a leading critic like Clement Greenberg today seems rigid and fundamentalist. He was espousing abstraction as a form of religion. Willem deKooning (1904-1997) was deemed lesser than Jackson Pollock (1904-1997) because he never freed himself from the figure. Greenberg apologized for Pollock’s late works in which the figure is evident. The purity of Greenberg’s dictums of abstraction conformed to the development of Color Field Painting and Formalism. Compared to which all else was anathema. With the curious exception of the now largely forgotten Horacio Torres (1924-1976).

The debate and speculation about a return to the figure among avant-garde artists came to a head when Peter Selz organized “New Images of Man” for the Museum of Modern Art in 1959. That seminal exhibition offers few clues to the dialogue that prevailed with such passion among American artists. Selz conflated European and American masters. On the A list there was an interesting face-off pitting Francis Bacon, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti and Cesar, among others, against the Americans Pollock and deKooning. Among the Figurative Expressionists he included Muller (by then deceased), Diebenkorn, Golub, and Nathan Oliviera. He flew wide of the mark with Leonard Baskin, Balcomb Greene, Rico Lebrun, Germaine Richier, Theodore Roszak, and Fritz Wotruba. They are artists more favorably regarded then than now. An exception was his inclusion of the eccentric H. C. Westermann.

Of the curators of his generation Selz had the best shot of defining the artists of the Figurative Expressionist movement but he blew it. When MoMA gets it wrong that stifles efforts to correct the mistakes. Shortly after that exhibition Pop art dominated the New York art world. Collectors, curators, critics and gallerists dumped Abstract Expressionism in a scramble for Pop. The signifying drip of Abstract Expressionism took on an ironic, sardonic twist in the early works of Jasper Johns and Robert Raushenberg. Roy Lichtenstein later transformed the signifying, fluid brush stroke into a hilarious cartoon.

If Abstract Expressionism was pushed aside Pop utterly buried the simultaneous emergence of Figurative Expressionism. With no major museums, curators, critics or galleries to take up the cause they were left to their own devices.

In Provincetown there was lively activity at this time with the legendary Sun Gallery. During the post war era artists flocked to the Lower Cape. Many studied with Hans Hoffmann and Henry Henche. They lived in shacks in the dunes, dug clams, and washed dishes in restaurants. Two of the artists founded the famous Ciro’s and Sal’s. There were exhibitions and panel discussions at the Provincetown Art Association. One of the most famous of these was the summer long Forum ‘49, in 1949.

What was seen and debated in P’ Town in the summer carried over to New York. Many of the artists who showed with Sun Gallery were struggling to find their way back to the figure. These included Tony Vevers (1926-2008), George Segal (1924-2000), Alex Katz (Born 1927). Red Grooms (Born 1937), Johnson and Thompson, Claes Oldenburg (Born 1929). Bob Beauchamp (1923-1995) Lester’s brother in law, Benny Andrews (1930-2006), Bill Barrell (Born 1932) and Jay Milder (Born 1934). Alan Kaprow organized one of his first Happenings at Sun Gallery

When the focus of Figurative Expressionism faltered the Rhino Horn movement was active from 1967 to 1978. These artists included: Benny Andrews, Luis Cruz Azaceta, Ken Bowman, Emilio Cruz, Peter Dean, Stuart Diamond, Mary Frank, Lionel Gongora, Joseph Kurhajec, Charles Parness, Peter Passuntino, Peter Saul, George Segal, and Nicholas Sperakas.

Of the first generation of Provincetown/ New York figurative expressionists the most important were Johnson, Muller and Thompson. Jan Muller died at 36 in 1958 and Bob Thompson was dead at 29 in 1966. Arguably Muller and Thompson were among the most gifted, inventive and lyrical artists of their generation. One may only speculate the impact had they sustained through longer careers.

While Johnson died at 91 the mantle of leadership rested uneasily on his shoulders. For his exhibition catalogue I endeavored to place him in context. Much of the material that appears above was included in an introduction. Through his daughter, Leslie DeTroy, I was informed that “Lester feels very strongly, however, that the ‘introduction’ section would be fine for a magazine article on art in general, or a book, but does not belong in a Lester Johnson catalog.” (From a letter, November 20, 1986).

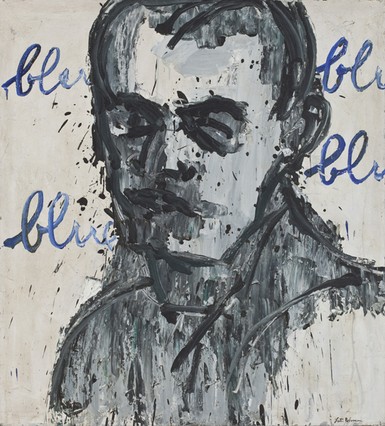

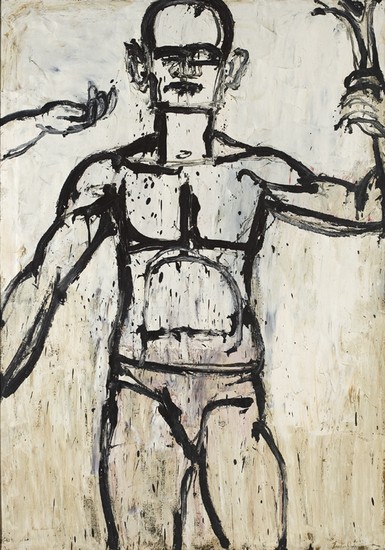

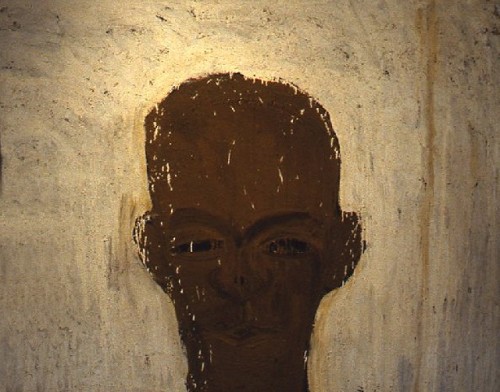

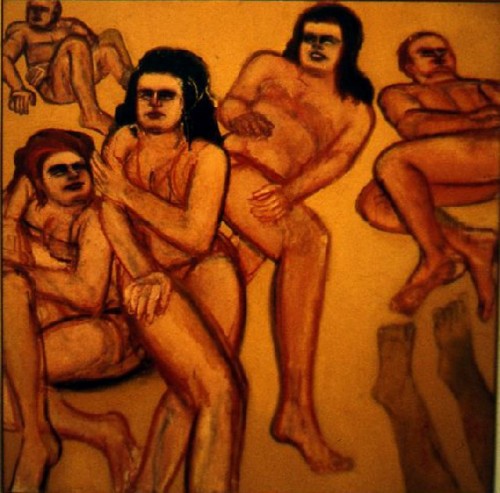

Then and now, however, it seems important to place the work into an historical context. Without this connective tissue the tendency is to view him as an eccentric or maverick. He was neither. In his formative years Lester was in the thick of the zeitgeist. It’s what informs the passion, energy, and enduring power of those early primitive works. There was angst and reckless risk taking. I feel something demonic in the frenzied execution of the early heads and figures. Taking from the Abstract Expressionists he painted from the shoulder in broad, messy, drippy strokes.

From that period is a video tape he gave me in the act of painting. It was an all out, intuitive, unthinking train wreck of an attack on the canvas. All of his guts and energy went into the frenzy of the creative act. There was no time or place for thinking and theory. Even today those early works blow me away with their fury and originality.

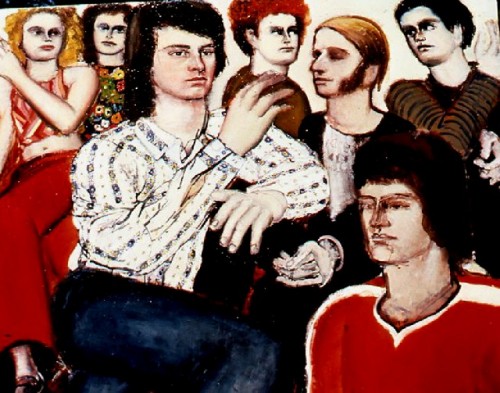

The Lester I came to know in the mid 1980s was very different from the glimpses of manic agita in that clip of vintage film. He was emotionally and financially comfortable. Even somewhat guarded and sedate. His unique approach to painting the figure had been filtered and formulated. He was an adjunct professor at Yale University. There were interesting ideas of teaching life drawing. The students were asked to draw with both hands or to start with the foot and work their way to the head. He was trying to break up the usual instincts. To evoke oblique and fresh approaches.

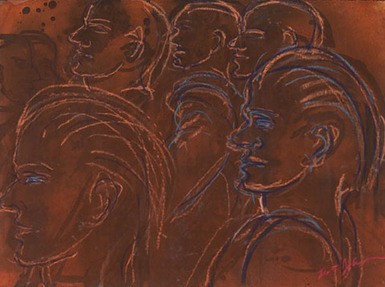

The secure life of a professor drew him away from the conflicts of the city. The Bowery, where he shared a studio with Larry Rivers early on, had been the source of inspiration and conflict in the work. There were the surging cityscapes, and cavorting Men in Hats. The urban environment was a locus for his inspiration. They were invented rather than observed figures with an emphasis on mass and volume. The figures were smashed into the space as rakish angles. There were vectors as they deflected humanistic impulses. Lester was striving to find the essence of universal man. The details and specifics failed to engage him. The figure was a metaphor for the turmoil and conflict flowing through him. The resultant works were among the most potent conundrums of his generation. Even now there is no consensus on what to think about them.

In a 2004 review Hilton Kramer approached the work as “…some painters have made it a fundamental tenet of their art to resist the templates of their own facility. Rather than aiming for ease of expression they deliberately cultivate certain obstacles to it, either through distortion in draftsmanship or by creating a facture that eschews suavity in favor of a distressed painterly surface. Figurative painters who came of age in the heyday of Abstract Expressionist aesthetic were especially likely to play a role in this effort to undermine the effects of facility.”

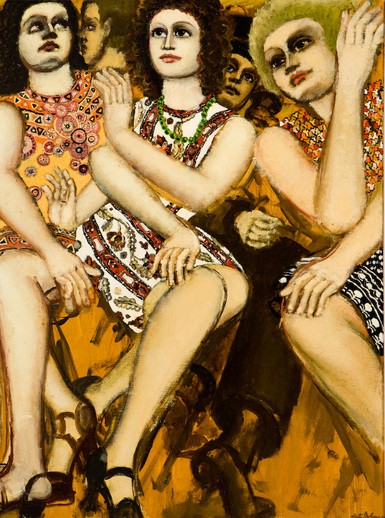

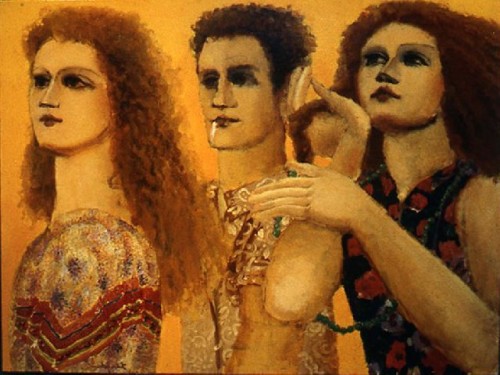

The trajectory from Skid Row and cold water flats to Greenwich, Connecticut and summers in East Hampton is vividly evident in the work. The generic bowler hats and boxy suits evolved into Yankee’s baseball caps. The strongly rendered, angular women became attired in the printed fabrics of designer Emilio Pucci. They intrigued Lester for their color and design. The profiles and soft, flowing hair of the women edged ever more to the classical. If his youth was devoted to Dionysus in later years he succumbed to Apollo. East Hampton inspired him to depict bathers on the beach.

During his student years in Chicago Johnson was painting small, impressionist landscapes. From 1947 to 1951 this continued in New York. The works were portable enough to take around to galleries. He told me it was an effective strategy “At least they can’t say ‘We’ll get back to you, just leave the slides.’ They either have to look at them (small paintings) or tell you to get them out of there.”

He got a response from the dealer Charles Egan who made a studio visit. Egan told him he didn’t have enough work for a show. “I was going to make more paintings for him” Lester recalled. “In the meantime I got involved with expressionism. When I went back to Egan I had paintings with wild figures and bright colors and he responded absolutely negatively. He even got angry and wanted to know what I was trying to pull. He thought I was wild. He liked me and liked my work enough to be angry…When I had a show (1951) at the Artists’s Gallery Charlie Egan came and saw it but again he was turned off.”

In 1954 Johnson showed with the Marvin Korman Gallery. The following year the stable was merged with the Virginia Zabriski Gallery. In 1962 he was taken on by Martha Jackson Gallery. In more recent years when David Anderson moved out of New York he returned to Zabriski. For the past few years Johnson has been with the David Klein Gallery in Birmingham, Michigan. Adam Zucker, a young scholar of the Figurative Expressionist movement, reviewed for us Klein’s recent exhibition of paintings from the 1960s. The gallery is in the process of negotiating to represent the estate. They were generous in allowing us to post many of the images that illustrate this article.

A change in Johnson’s work occurred in 1951. Over a two week period he was using a mirror to paint a self portrait. One afternoon he painted out the image. “I was free to start again” he recalled. “I had three colors on my palette and started making diamonds. Two on the top, two on the bottom, and two on the sides, one in the middle.” He realized that it was about his family and that “I was the one trapped in the middle.” I asked Lester if he still had that painting but it never surfaced.

In the Kramer piece in the New York Observer (October 24, 2004) he quotes a Dore Ashton catalog statement. She wrote that the change to expressionism occurred when Johnson saw a Giacometti exhibition at Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1948. Lester never mentioned that to me. I do not know if any work of that period survives. Kramer compared the paintings of Johnson to the paintings and sculptures of Giacometti. It strikes me as an apples and oranges argument.

Lester elaborated on the importance of the Diamonds painting (my title) from 1951. “I thought that this painting really worked. It really goes across the canvas. It goes up and down. It’s natural. But then I said ‘no it’s not done.’ I took a tube of paint and squeezed it right out of the tube painting faces in each of the seven diamonds. I was real happy but I had no idea what it was all about.”

There is a visceral series of heads mostly in small scale owned by the Lannan Foundation. J. Patrick Lannan, like Walter Chrysler and Joseph Hirshorn, was noted for buying the content of an artist’s studio at bargain basement prices. While it exploited cash strapped artists this also had the result of preserving key periods in depth.

During annual visits to Palm Beach to visit my mother I always enjoyed driving over the Bridge to West Palm Beach. The Lannan Foundation occupied a former movie theatre. There were many curiosities. This included an important series by Johnson. They were almost minimalist monochromes (from the 1960s) in which the features were scratched into the paint. Now that the Foundation has moved I don’t know what has become of these works. There was an intriguing transitional series by Morris Louis on the cusp of developing Color Field painting. Lannan also bought early work by Julian Schnabel and Robert Longo.

During the 1950s Abstract Expressionism dominated the New York School. The artists hung out at the Cedar Bar in Lower Manhattan. During a Spring break from college, around 1960, I sought out the famous artist bar. I was expecting to run into deKooning but it was just a quiet night. After a couple of beers I moved on to the Café Wha. Decades later Irving Sandler told me about how he ran the panels and lectures at the Artists’ Club. Lester was a member.

“There were always fights up there” he recalled. “It was a mess to get into the place, but once you got in, it was organized. Every Friday night they would have a panel and it was like a Union Hall meeting. There was always a bottle of liquor on the speaker’s table. They tried to establish a frontier mentality. Just guys sitting up there drinking and talking. Nobody was going to stick their neck out in that kind of a situation. It was seldom that you got anything really meaty. There were fights between factions. But there were no figurative painters there. I mean I was a figurative painter. Philip Pearlstein was a member but he wasn’t painting the figure at that time. Alfred Leslie was a member but he was doing abstract work. It was pretty much an abstract expressionist club. I was on a panel a couple of times and I took my lumps but got my two cents in. I was asked to give a live presentation of my own work. Years later I ran into Ray Parker who remembered my talk and asked if I still paint using both my hands.”

Although Johnson and Thompson were not included in New Images of Man they were increasingly respected in the community of artists. In addition to the art world Thompson was hanging out with jazz musicians. His masterpiece Garden of Music (6 x 12’ the Wadsworth Athenaeum) depicts an ensemble of avant-garde musicians including Ornette Coleman and Charlie Haden.

From 1961-62 Johnson accepted a position as Artist-in-residence at Ohio State University. As he conveyed to me it was the wrong time to be out of town. When he returned everything had changed. It was precisely the moment when Sam Hunter, the founding director of the Rose Art Museum acquired some 25 works with about $40,000 from the Mnuchin and Gervitz families. Hunter hedged his bets with acquisitions of Abstract Expressionism, Color Field, and Pop Art. Significantly, he ignored examples of Figurative Expressionism. It was the Pop selections that are now evaluated in the millions. Prime examples of Figurative Expressionism from that period are estimated in the low to mid six figures.

By 1964 Jack Tworkov the chair of the department recommended Johnson for an adjunct position at Yale which continued until 1989. From 1969-1974 he was the Director of Studies for Graduate Painting.

After that frustrating attempt at a self portrait in 1951 Johnson rarely painted from observation. In 1971 James Joyce surfaced in an ensemble of men in hats. There is a portrait of his son Tony. By the 1980s the figures and costumes were more decorative and representational. But as Kramer correctly observed he resisted becoming too facile. Arguably he was picking up details of the world he lived in. From the t-shirts of Tony and his pals to the colorful dresses of the social circuit in Connecticut and East Hampton.

Of these more colorful and decorative elements he said “I don’t think that they should be fashion. I really don’t. I think they have to be more universal. I used Pucci, the colors, and the design. But I try to make it into a harder content. I mix things up. No one would ever wear that. You just wouldn’t put these two together. I think it’s important to keep it universal. If it becomes specific fashion it points to limitations. I don’t like specifics in that sense. I don’t like paintings that tell stories. I’m not involved with any kind of anecdotal painting.”

In the 1965 book “The Success and Failure of Picasso” the critic John Berger discussed the negative impact when an artist is isolated from his peers. Wealth and fame built a wall around Picasso. With Lester a self imposed isolation from artists and the mainstream was a personal choice. I found him comfortable, almost bourgeois. He seemed to have little interest in the art world which largely returned the favor. There was an understated resentment about being passed over. And yet, as I stated with disappointment, he resisted having his work discussed in comparison to and in context with other artists.

By then the art world was all about fame, ego and money. Lester wasn’t interested in that. Commenting on the commercialism of the art world he told me “You go back to Titian and Rubens and I think you wouldn’t find that to be true. They had something to say. There was something more for them than just making art. Art was a vehicle for their expression. Once you got into ‘Art for art’s sake’ it’s like listening to yourself sing. There is no communication and there’s no priority for expression. Art just becomes something to buy.”