Eastland at Chicago’s Lookingglass

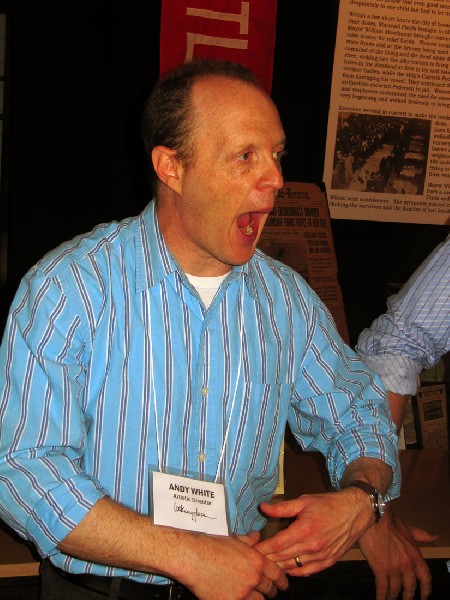

Premiere of Andrew White Musical

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 18, 2012

Eastland

Written by Andrew White

Music by Andre Pluess and Ben Sussman

Directed by Amanda Denherst

Stage Design, Dan Ostling; Costume Design, Mara Blumenfeld; Lighting, Christine A. Binder; Music Arrangement, Amanda Denhert; Music Director, Malcolm Ruhl; Co-Sound Designer, Josh Horvath; Co-Sound Designer, Ray Nardelli.

Cast: Jeanne T. Arrigo (Sister, Musician and Others), Lawrence E. DiStasi (Otto, Olaf and Others), Christine Mary Dunford (Marianne and Others), Doug Hara (Reggie “the Human Frog’ and Others), Derek Hastenstab (Husband, Houdini, Musician and Others), Erik Hellman (Grocer, Musician and Others), Malcolm Ruhl (Musician and Others), Michael Barrow Smith (Captain Pedersen, Musician and Others), Scott Stangland (Ernie, Musician and Others), Tiffany Topol (Solveig, Musician and Others), Claire Wellin (Bobbie and Musician), Monica West (Ilse)

Lookingglass

Chicago

June 6 to July 29

Running Time: 90 Minutes

Andrew White, the artistic director of the 2011 Tony Award winning Lookinglass, has written a musical Eastland with music by Andre Pluess and Ben Sussman based on a disaster that took 884 lives.

On 24 July 1915, the Eastland and two other Great Lakes passenger steamers, the Theodore Roosevelt and the Petoskey, were chartered to take employees from Western Electric Company's Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois, to a picnic at Michigan City, Indiana. This was a major event in the lives of the workers, many of whom could not take holidays. Many of the passengers on the Eastland were Czech immigrants from Cicero, Illinois; 220 of them perished.

Commissioned in 1902, the long, slender, knife like hull, with too much superstructure was built for speed. It was known as “The Speed Queen of the Great Lakes” for its swift delivery of produce to markets. It was reconfigured from its original function to serve as a cruise and excursion craft. There were structural changes that compromised it stability.

Following the loss of 1,500, when the RMS Titanic sank in 1912, in compliance with a resulting law the Eastland added several lifeboats. A rotting upper deck was repaired with a layer of concrete. This added critical weight above the center of gravity, or tipping point, of the vessel. This was designed to be counterbalanced by taking on water in its tanks flanking the bottom of the hull.

For the company excursion passengers began boarding the Eastland on the south bank of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets around 6.30 a.m. By 7:10 a.m., the ship had reached its capacity of 2,572 passengers. The ship was packed and began to list slightly to the port side (away from the wharf). The crew attempted to stabilize the ship by admitting water to its ballast tanks. Sometime in the next 15 minutes, a number of passengers rushed to the port side. At 7:28 a.m., the Eastland lurched sharply to port and then rolled completely onto its side, coming to rest on the river bottom, which was only 20 feet below the surface.

Considering the loss of 884 lives the Eastland sinking is on the short list of national disasters. Compared to the sinking of the Titanic, however, it is relatively little remembered even by citizens of Chicago. They recall the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, or when the Cubs won the World Series in 1908, but are mostly clueless about the Eastland.

Given the obscurity of the event, and the challenge of its scale, one must admire the ambition of White to present the event as theatre and with the more formidable degree of difficulty, a musical. It premiered for the media before a deeply moved and enthusiastic audience on Saturday night. Eastland struck me as more a work in progress than a polished production.

Casting off, which actually never happened, is as much a theatrical conundrum as an historical fact. We never really got a strong sense of who these people were and what this rare day off from sweat shop conditions meant to them. There was the sense of an ensemble, with many actors performing multiple roles, rather than a focus on individuals. The complication of sorting out characters was further obfuscated by a number of the musicians doubling as actors.

This was particularly evident in casting Captain Pedersen (Michael Barrow Smith). We first encounter him as a elderly, portly, acoustic guitarist and balladeer. His singing never rose beyond generic and one might say the same for his dramatic range. He has a key scene late in the play when standing accused of blame for the disaster. The familiar reply was along the lines of “just taking orders.” Grilled as to whether the ship was overbooked that day his response was that the number of passengers complied with limits set by inspectors. We learn that the vessel had a history of instability.

It was difficult to get a fix on the music. There was an attempt at regional and period naturalism. The instrumentation was dominated by strings- guitars, banjo, violin, bass, piano with a dash of accordion. The music was for the most part somber but ultimately as unmemorable as the Eastland itself. The score was ersatz volkish evoking the mid western Americana of the turn of the century. Think of an orchestrated Burl Ives.

As an ensemble work, lacking singular, show stopping, catchy tunes, the music was somber, deeply felt and warmly compelling. The score and lyrics well served advancing a herky jerky book. This was exacerbated by flash backs of the victims as well as forward thrusts conveying the impact on families of survivors.

Of the 884 victims we are only given a few thumbnail cameos. As a signifier of the factory workers we meet the immigrant Ilse (Monica West). At the Western Electric Company she and other women wind wire onto spools which will then be woven into cables. She is ‘fortunate’ to find a hard working husband, a cable layer. It is a tedious marriage. There is an improbable, flirtation/ affair with a grocer (Erik Hellman). While her husband is working the night shift Ilse tastes the forbidden fruit, in this case, seduced by an avocado. The evocation of the “apple” of “original sin” was too knee jerk obvious. On that fateful day she fails to hold on to her seven-year-old son.

Instead of being expelled from the Garden of Eden this Ilse/Eve will suffer the wages of sin by going down with the ship. Which, I guess, makes this a tragedy of Biblical proportions. Aren’t they all?

While the unfolding of the tale of the Eastland is as murky as the dank, polluted, foul river it sank into the musical has been staged brilliantly. Much credit goes to the inventive design of Dan Ostling. There is an effective use of trap doors which convey those caught in the submerged hull settled in 20’ of water. There is a tent-like enclosure flanking the sides and over the stage of the mid-sized theater. With a thunderous clash (Co-Sound Designers, Josh Horvath and Ray Nardelli) the sheets come down in a flash to reveal a pipe structure evoking the ship's innards.

As in the film Titanic we were mostly following an enervating plot line until the ship sank. There is a sharp dramatic shift from a bucolic frolic to the high energy of disaster.

During the opening gathering of the excursioners on deck, all wearing period costumes designed by Mara Blumenfeld, we wondered why Doug Hara was bare-chested. Initially it made no sense. During the disaster aspect of the musical he emerges as the drama’s most stunningly singular and compelling character based on the true life, 17-year-old Charles R. E. Bowles recreated as “Reggie the Human Frog.” Over some 11 hours, until he was forcibly removed from the scene, Bowles pulled some 40 living and dead to the surface.

During one of those many dives he interacts with a hysterical Ilse riven by guilt for abandoning her son. She demands that Reggie look for her boy. Subsequently, she drowns and is among the shades evoked to tell their sad tales as wet, dripping garments, poignantly signifying the victims, are hung on pegs and hoisted aloft. It was a beautiful example of stagecraft.

He finds a girl alive in an air pocket. He urges her to dive under the hull with him. But she is too afraid and clings to her precarious perch. Reggie promises that he will tell rescuers. When they start to cut into the steel hull the captain warns that it may spark an explosion.

In an emotional high point of the musical there is a breach of light above and a rope loop is lowered to pull her to safety. We watch with fascination her slow ascent up the scaffolding then a quick return to the stage for the ensemble finale.

While we are riveted by the performance of Hara, who superbly raises the emotional bar of the production, he is curiously, and wrongly, upstaged by the patched in character of the legendary escapist Harry Houdini (Derek Hastenstab). There is an improbable and distracting plot line of a ‘competition’ between the divers as to who holds the record for the longest time underwater. Do we need to know that these “rivals” practice in their bathtubs? Eliminating the distracting Houdini subplot might allow for fleshing out some of the other characters.

We saw this musical with a group of critics meeting in Chicago as members of the American Theatre Critics Association. Of course one wanted to get a sense of peer responses. In general critics are reluctant, as am I, to tip their hand prior to posting a review. Or to be influenced by other opinions. But it was unique to have so many of us, including Chicago’s working press, all attending the same event. Just sampling one liners, for which critics are notably adept, these ranged from unvarnished raves to a witty colleague who remarked that he was "Glad they all drowned.”

There was flat out cheer leading from Chicago Sun Times critic Hedy Weiss whose lead reads “It is an unmitigated thrill to be present at the birth of a transcendent work of theater. And “transcendent” is the very best way of describing “Eastland,” the fiercely original and wholly transfixing balladlike musical that received its world premiere Saturday at Lookingglass Theatre.”

In a more analytical treatment in the Chicago Tribune Chris Jones finds it “theatrically muddy but emotionally powerful.” Johnathan Abarbanel in the WBEZ 91.5 blog calls it "... a blue-collar musical; a show as unglamorous and modest and accessible as the folks who boarded and died on her."

Eastland is Chicago-centric, both in its historical inspiration, and production by a renowned theatre company. Perhaps that is reflected in the coverage by the papers of record. It is challenging to voice the opinion of an outsider. By coincidence the Red Sox were also in town playing at Wrigley Field (They took two out of three from the hapless Cubs).

It was a thrill to visit the renowned theatre. The company was founded in 1988 and was itinerant for many years. Lookingglass moved into a permanent home in 2003—a brand-new theater in the newly renovated Water Tower Water Works on Chicago's Magnificent Mile.

We got a strong sense of the superb production values of a great company. With judicious revision Eastland may well come to a theatre near you. It would be interesting to see how such a Chicagocentric musical would play on the road. Away from a partisan hometown audience will prove whether this musical is ready to sink or swim. It may take more than Harry Houdini to turn that trick.