The New Realism: Ananian, Deyab, Lee and Mugar

Why We Fight

By: Martin Mugar - Jun 18, 2014

I am not talking about Realist art per se, although a realist painter will be included in my discussion, but an attitude toward life that is realistic. I first touched on this in my critique of the Boston ArtScene and the Marathon bombings. I had just finished up a show in Boston that winter with Paul Pollaro. I had not shown in Boston since 2007, so it was a re-acquaintance with the Boston art world. The then current Boston art scene seemed to me to be more interested in providing well-crafted objects and weak sentimentality than with trying to understand the depths of the world we live in. Just the ripples on the surface not the powerful forces that shape that surface.

The political elite’s reaction to the Bombings later that Spring seemed to say that they had rather support a veneer of meaning, propped up by platitudes, than deal with clarity about the nature of the world that produced such horror. In the case of the Marathon deaths, the political class brought out the big guns to channel Boston’s enthusiasm for sports to heal a an emotionally rattled city overcome by this tragedy. It all reeked

I recall in high school working late one night on an essay on Moby Dick. I could not figure out the mystery of it all and the solution of a mystery seemed to be essential to the book and to writing a successful essay. Who is Ahab, what drives him? How do we function is a world shaped by mad people? It seemed ridiculous to hand in a paper that left the big questions unanswered. I am sure that most of my classmates could have cared less. I remember going to bed at midnight, the night before the paper was due, somewhat disheartened with my unresolved essay, only to wake up a few hours later with an insight into the problem. It lay in the “Try Works” chapter.

Recently, because I couldn’t remember what the chapter was about , I googled the title of the chapter. I was not surprised it was a meditation on the need for perseverance and faith as one passes through the dark night of evil and sorrow, captured by the patterns of fire and smoke spewing from the rendered flesh of a freshly killed whale. “There is wisdom that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness.” says Ishmael. How do we navigate that distinction? It made me think of Clint Eastwood in “The Outlaw Josey Wales” who hovers between the two woes; one a wisdom born of sorrow; the other a kind of madness, akin to

All I have reread at this point is that chapter but I am astonished how much there is to unpack in each sentence. The end of the short chapter describes Ishmael’s realization that he has been steering the Peqoud ass-backwards and is close to capsizing the whole boat for me is a searing image of an upside down topsy-turvy world full of mistakes that are combined to weave the fabric of reality itself.

There are a handful artists, and I will include myself include, who are emotionally robust enough to look at the shape of things and depict them accurately. I think the key to their way of thinking and feeling is an ability to see things in context: a kind of intuition of the whole or a knack at seeing what “is” in the context of the unseen.

Larry Deyab at first glance can appear to be a so hip and contemporary with his preferred use of spray paint, photographic journalistic source material and a Richard Prince sense of the edit and erasure. But his art embraces a totally un-contemporary sense of horror more akin to Goya than Prince as he responds to the ongoing chaos of the Middle East. His preferred media of spray paint provides an identification with the lives of the victims who have been reduced to poverty and terror and if asked to paint their condition could not go the a fine art store to buy brushes. It conveys a sense of urgency and identifies with the victims with the brush of urban anger,spray paint. His subject matter heretofore dealt the Arab-Israeli conflict, now stands aghast before the unwillingness of the Western powers to engage in the Syrian conflict that is moving rapidly toward genocidal proportions: Images of blind fate, the hammer of doom. Victim and victimizer. The emotions go beyond the photo journalistic source of the images but seem more akin to some generational and macabre dance of evil.

Excess is at the heart of these conflicts. Over the top annihilation of the opposition, a fury that knows no boundaries. Confronting and engaging this aspect of life and death is not something easily achieved with Realism, nor with Abstraction for that matter. I attempted to engage these issues in my work from the late Nineties , shown at Crieger-Dane in Boston and has remained an issue that seems to escape the critics. Or maybe they see it but it is that very notion of excess that puts them off. Somewhere in my career I lost any desire to make art as a vehicle of self-expression.

The Neo-Expressionism of the 80’s seemed to be the last gasp of that self-centered version that came out of Germany in the 20’s and 30’s.I wanted a language that would embody the state of things of things as they are. Things as they are swimming in a sea of forces bigger than themselves. But also as inevitably forced into conflict with each other. The titles of the work gave them away: “Mackerel crowded sea “,”Sargasso Sea”, “Footprints”. The first title is taken from Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium”, a poem that establishes a sharp contrast between the modern reality of man as swarm and a more god based hierarchy that lends a ground of eternity to our individual existence. “Sargasso Sea” created in my mind a sort of organic island without substance that houses enumerable species….”Footprints” imagines a larger force squashing lesser forces. The latter title and painting is no permission to this sort of oppression but a rather sang-froid description of academic politics. I have always felt that the sadism that we love to imagine is so far from our day-to-day lives virulently in the perverse little politics of the world we work in.

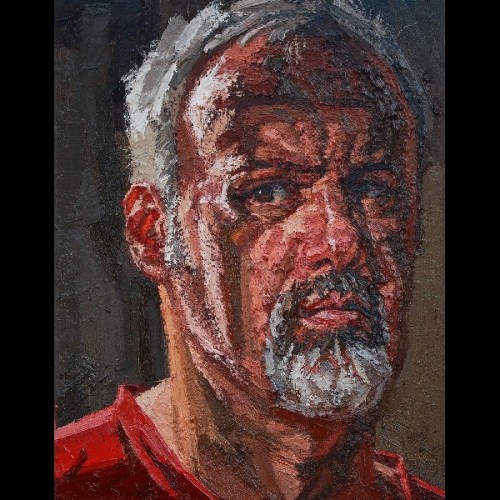

Mike Ananian’s realism evokes implicitly a kind of male stoicism that reminds me of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman”: the life of someone who has to get up for work each morning to fulfill his sales quota, whether there is pleasant background music or not. I also think of Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross”, where real estate brokers driven by the Darwinian will to prevail, are capable of undercutting their colleagues, selling questionable properties and committing a crime. There is no room for humor or grace, only the superficial sense that their life of struggle has some heroic meaning. The characters in Ananian’s portraits seem to carry their faces like Roman portrait busts without any halo of divinity.

They are strangely reminiscent of his UNC-G colleague BillyLee’s sculptures of heroic hoplite heads. Guardian’s and sentinels that are oddly eye less. They don’t observe anymore; they have been reduced to pure will. They are holding their ground full of a contained phallic

Maybe my work and the work of Deyab, Lee and Ananian is lacking in irony, the staples of contemporary art. We are clearly not fetishistic in our creation of art objects but forcing our images to remind the viewer of the hardness of survival. No bromides, no fatuous statements about commodification. This work is not fun. No matter how hard we try to find fantasies about the human condition and leaders and gurus to fulfill them we can’t escape the grim reality of conflict.

Reposted courtesy of Martin Mugar from his site Painting.