Caucasian Chalk Circle at Classic Stage Company

Brecht's Liars, Killers, Cheats, and Self-Servers

By: Edward Rubin - Jun 19, 2013

The Caucasian Chalk Circle

Playwright: Bertolt Brecht

Translation: James and Tania Stern

Lyrics: W.H. Auden

New Music: Duncan Sheik

Director: Brian Kulick

Set Design: Tony Straiges

Costume Designer: Anita Yavich

Lighting Designer: Justin Townsend

Sound Design: Matt Kraus

Classic Stage Company

136 East 13th Street

New York, New York 10003

212- 677- 4210 x 10

Closes, Sunday: June 23, 2013

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) and I are in total agreement that mankind, not us but them, as I like to say to avoid argument, is populated by liars, killers, cheats, and self-serving louts. One only need to look around, listen to the daily news, or for that matter attend any one of Brecht’s more popular plays to meet these people.

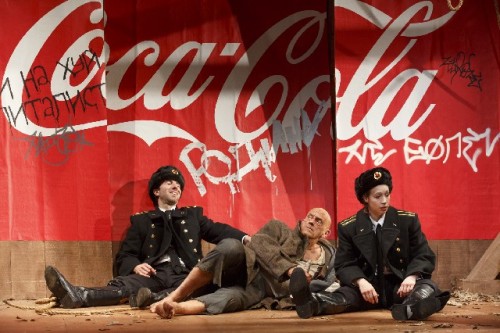

Serving up a dish of rotten folk, with one or two good ones thrown in for good measure, is the Classic Stage Company's production of Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle nicely directed by CSC’s artistic director Brian Kulick.

The “play within a play” opens with a scene-setting prologue, updated to include recent events such as Chernobyl. The prologue’s ultimate purpose is to let us know up front – and know we do, down to our very bones – that no matter when or where or what is happening on stage, the play is essentially about us and the times we live in.

In the background, further indicating time, place, and circumstance, we see a partially destroyed statue of Lenin. A change of government is in the air.

The first words to fall on our ears come from the camp mouth of a flamboyantly made-up Mary Testa. She is quickly joined by Alex Hurt, Deb Radloff, Jason Babinsky, and Tom Riis Farrell, a chorus of actors, all of who deliver their scene-setting lines in Brecht’s typically exaggerated anti-realist style.

Mary: “Moscow is nothing but ministries, ministries, ministries. Ministry of this, ministry of that.”

Alex: “I heard they are now selling sausage contaminated with pesticides, hormones and radiation from Chernobyl.”

Deb: “Our revolution was a disaster. Our revolution -- all it did was make it possible for the most evil people to have the most power.”

Jason: “It's hopeless. And this will go on forever and ever. It's always like this in Russia.”

Tom: “What is one Russian? -- A fool, And two Russians? -- A fight, And three Russians? -- A Vodka line.”

The “frame” play takes place somewhere in the Soviet Union around the end of the Second World War. It opens with a dispute between two communes, a fruit growing commune and goat farming commune, over who is to manage an area of farmland after the Nazis have retreated from the village.

To shed light on the dispute, a parable play is organized by one of the communes with all of the actors, except for Elizabeth A. Davis, a 2012 Tony nominee for Once, playing multiple roles.

The through line of this play is simple—a peasant girl Grusha (sweetly played by Davis) rescues a baby that the fleeing Governor’s wife (Mary Testa) inadvertently leaves behind after her husband is killed during a coup. Thus begins Grusha’s flight as she attempts to keep the baby from the new ruler, the Fat Prince (Tom Riss Farrell), and his Ironshirts Gestapo-esque guards, who want to kill it.

Along the way, as Grusha crisscrosses the landscape, all the time being chased by the Fat Prince and his gang, she falls in love with a handsome young soldier (Alex Hurt), crosses a range of treacherous mountains to live with her brother and his wife, eventually ending up, in one of the play’s more funny scenes, marrying a dying man (Jason Babinsky).

To usher the audience along this journey and punctuate each plight as it unfolds – a little hand-holding is definitely needed – Brecht employs a narrator called The Singer. His role, frenetically played by Christopher Lloyd – he chews up the scenery in both acts – is to impart the inner thoughts of the play’s various characters, as well as to signal the changes in scene and time.

As act one ends, The Singer announces:

“The Ironshirts took the child away, the precious child. The unhappy girl followed them to the city, the dangerous place. The real mother demanded the child back. The foster mother faced her child. Who will try the case, on whom will the child be bestowed? Who will be the Judge? A good one, a bad one?”

As it turns out, act two, seemingly another play, yet set within the same war setting, centers primarily on Christopher Lloyd, whose vocal and physical calisthenics continues to turn the stage into his private fiefdom, not unlike Mark Rylance’s 2011 Tony winning performance in the play Jerusalem which had him rolling around the stage.

Here, Lloyd goes from playing The Singer, to becoming Azdak the village clerk cum bribe-taking judge. His outrageous behavior which supplies much of the play’s levity, favors the poor, the oppressed and good-hearted bandits. The play ends with Grusha and the Governor’s wife, each claiming the right to keep the baby, standing before the Azdak in court. His judicial decisions, zany, purposeful, and happily accidental, change everybody’s world.