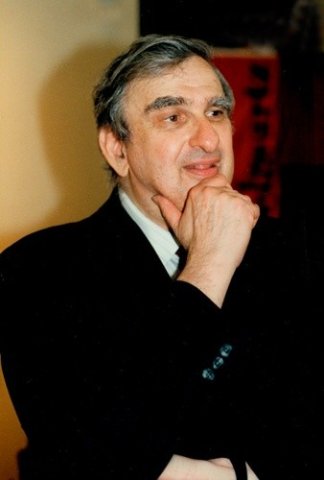

Theodore E. Stebbins MFA Two

Pollock's Troubled Queen Among Many Acquisitions

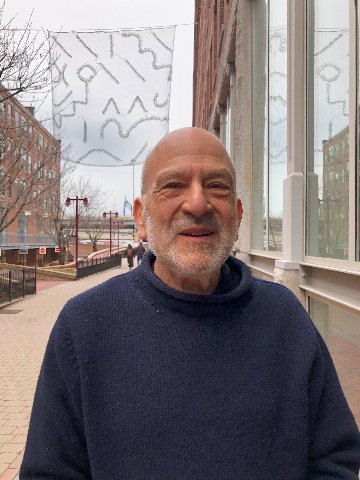

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 20, 2020

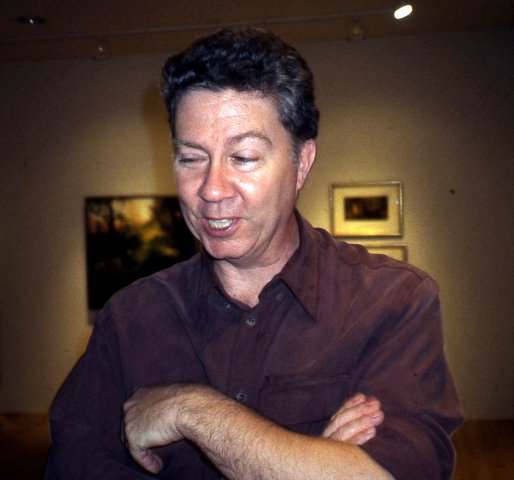

When John Walsh left for the Getty Museum, and with a hiatus in the contemporary department, Theodore E. Stebbins, chaired three departments. He seized the opportunity to acquire American and European modern and contemporary art. There were huge gaps to fill when works that now command millions were relatively affordable.

Charles Giuliano You were interested in the group of Northampton realists.

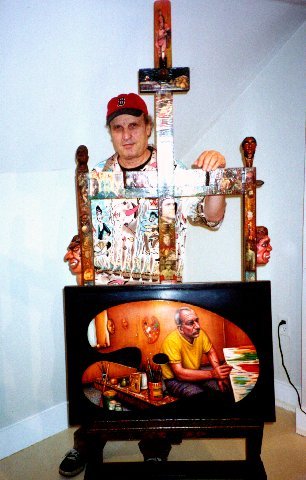

Ted Stebbins I’m glad you noticed that they were worth noting and recording. The realism that Gregory Gillespie (1936-2000) and others practiced shouldn’t be forgotten. I have great respect for abstract art but I don’t think it’s fair or right to neglect talented people like that. They were very honest and dedicated artists.

CG Greg was a genius of his generation. No less so his first wife Frances Cohen Gillespie (1939-1998). Also, Jane Lund (B. 1939), Randall Deihl (B. 1946), and Scott Prior (B. 1949).

TS I got a great Scott Prior of his wife “Nanny and Rose” (1983) on their porch.

CG You acquired a group portrait by Randall Deihl.

TS That painting “Lust for Life” is a great visual summary of those artists. I got to know them. They are connected to Boston. In a way they were local artists and homogeneous enough a group to make sense of. I didn’t see anything like that in Boston.

CG I was embedded with the Boston art world and greatly disagree. Did you look at Henry Schwartz (1917-2009), Gerry Bergstein (B. 1947), (Bob Ferrandini, and Domingo Barreres)?

TS I didn’t think much of Schwartz’s work but I liked Bergstein’s. He’s absolutely one of the best Boston painters. I had one in the exhibition of Boston collectors.

CG You’re holding up the catalogue. Who were the important collectors? Other than Graham Gund and the Paines (Stephen and Susan)? I regarded Gund primarily as a checkbook collector in the sense that he was buying already established, blue chip artists.

TS Checkbook or not, in this catalogue (Boston Collects 1986) you see Graham owning some fabulous works. Some of the best artists in America including Frank Stella (B. 1936) at his absolute best. He owns a great Jasper Johns (B. 1930) a couple of (Mark) Rothkos (1903-1970). He was after big game. You can’t talk about would you rather have a Rothko or a Gerry Bergstein? I was trying to catch up to help put the MFA on the map.

CG Your point is well taken. But we are talking about great collectors like Maxim Karolik and William Lane. In a sense they were first responders. As you have commented, what Karolik collected inspired you and other graduate students at Harvard. The collector had discovered luminism not curators and critics. You learned of those artists through his vision. The same may be said of Lane who was unique in buying artists before taste, criticism, and the market caught up to him.

Gund, and wealthy collectors like Eli Broad (whose collection was shown at the MFA) did nothing to establish the career and reputation of the artists they acquired. When they bought work, it went to the highest bidder. Compare that to say, Robert Scull, who bought from studios and established the market value for Pop artists. There was great resentment when he cashed in on that body of work. Like Charles Saatchi he used the money to refinance collecting the next generation.

Dorothy and Herbert Vogel were people of modest means who filled an apartment with works of minimalism. The artists became their friends. What they acquired for a pittance became priceless. They were true collectors.

Karolik and Lane were risk takers. They were ahead of the curve. They were taste makers who made the MFA what it is today.

TS You’re absolutely right. What Karolik and Lane did is hard to imagine. Don’t forget that Lane did it again when he discovered photography in the late 1960s. He formed the greatest private collection of photography in the world.

CG What about the Wagstaff collection?

(Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr. (1921-1987) was a curator, patron and collector. In 1973, with the assistance of his lover Robert Mapplethorpe, he believed that art photography was significantly undervalued. Over the next decade, he assembled one of the most important private collections of photographs in the world. He sold his collection to the J. Paul Getty Museum in 1984.)

TS Sam was a very good collector and adventurous in later decades. Lane was there in the late 1960s. So, they are very different. I love the Wagstaff collection. In collecting, how a few people get into things before anyone else does, is one of the great mysteries.

CG Do you believe that the museum has an obligation to collect the artists of Boston? To support local galleries and the art community? This has been the case in other cities. Most notably in Chicago and of course New York or LA. That in turn enhances the national reputations of artists and communities. To some extent that exists with the former Boston Now exhibitions of the ICA currently the annual Foster Prize. There have been annual New England surveys of the De Cordova museum. The MFA has the sporadic Maud Morgan Prize for women artists.

TS I know that’s your favorite subject. I admire what you’ve done with that. The Boston artists need a champion and you, Sinclair Hitchings, and some others filled that role admirably. (Marjorie) Jerry Cohn was the long-time print curator at Harvard. She spent a lot of time going to see local artists and buying prints. That was a fantastic, wonderful thing. The local printmakers were connected and recognized. Their works are now in Harvard’s distinguished collection.

For me, I had limited responsibility in contemporary art for a short time. During that period, I wanted to acquire the best available modern artists. I had a brief opening to do that. Buying Boston school painters wasn’t on my agenda. Sorry to say.

(Those artists have been collected by the Boston Public Library, the Danforth Museum, The De Cordova Museum, Fitchburg Art Museum, The Rose Art Museum and The Provincetown Art Association and Museum.)

CG I liked your comment that you were a big game hunter. There’s nothing wrong with that.

TS Boston had so far to catch up. Still has.

CG That game wasn’t big because you made it big. It was already big. You just had a big rifle.

TS I had a nice-sized rifle. The 1980s was a great moment in time. Works by great artists could still be bought for a few hundred thousand dollars or less. Like Warhol, Lichtenstein, Richter, those works cost millions now.

CG Does that describe the (Anselm) Kiefer (B. 1945, “Untitled” 1984)?

TS We got that (from Marian Goodman Gallery) for about $70,000. At the time that was a ton of money. I don’t think the (George) Baselitz (B. 1938) was much more.

CG In my 1984 interview with Jan Fontein, I quoted from a then recent Boston Globe article with MFA curator Amy Lighthill. She stated that “You can buy twenty Doug Andersons (B. 1954) for the price of one work by Chuck Close (B. 1940).” Who hired Amy?

TS I did.

CG If you describe me as a champion of Boston artists, she certainly had that role. She was close to artists and the community.

TS Amy is a very wonderful person. As you say, she was very dedicated to artists. But in retrospect, hiring her was a mistake of mine. I could have hired anybody. When I met Amy I was so excited. She seemed good. I should have looked for a better trained, more intellectual, young modernist. It wasn’t Amy’s fault at all. She did well and was nice to work with. I feel badly about this but I put her in a position she wasn’t quite equipped for. Looking back, what it meant for history, I didn’t do her a great service. Or the museum.

On the other hand, she did a wonderful show of Sean Scully (B. 1945). He is a very tough painter whose reputation continues to rise. She also did a very good Leon Golub (1922-2004) exhibition. Those are two excellent shows that Ken (Moffett) would never have done. Ones I wouldn’t have thought of doing myself.

CG Wasn’t she close to the Northampton group? Wasn’t it through Amy that the museum acquired Gillespie’s “Imaginary Pregnancy?”

TS I don’t think so, though it’s possible. I went several times to see Greg and his wife Peggy. I don’t remember Amy being part of that. But I could be wrong.

CG I had negotiated with Nielsen gallery to curate an exhibition of Gillespie’s psychedelic paintings. They didn’t sell, but it was very interesting work and I was excited about showing it. Just before the show he died (suicide) and the project was cancelled.

TS That was such a shock and I still remember when I heard about it. Did you see the show we did with Greg and Fran’s work?

(Life as Art, Paintings by Gregory Gillespie and Frances Cohen Gillespie, 2003-2004. From Harvard’s PR “In conjunction with the exhibition Life as Art, a fully illustrated catalogue-the first publication of the Fogg Art Museum's new department of American art-has been produced. The publication includes essays by the Stebbinses on the lives and work of the Gillespies, and an essay by Fred Licht, curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, on the dark side of Gregory Gillespie's work. The catalogue draws on Gregory's unpublished journals, which were made available by the Gregory Gillespie Trust, and an extensive series of letters from Frances to her friend the novelist Zane Kotker, who shared them with the authors.

“In November 2002, the Harvard University Art Museums established the department of American art at the Fogg Art Museum and appointed Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., as its first curator of American art. The exhibition is organized by Stebbins, along with his wife, Susan Ricci Stebbins, an independent scholar; both shared personal and professional relationships with the Gillespies.”)

CG I was close to Fran and included her in a 1988 traveling exhibition (Maris Gallery, Westfield State College, Montserrat College of Art and The Dodge Gallery, Northeastern University) Here’s Looking at You: Contemporary New England Portraits (James Aponovich, Gerry Bergstein, Mira Cantor, Randall Deihl, Elsa Dorfman, Frances Cohen Gillespie, Jane Lund, Scott Prior, Suzanne Vincent, Kelly Wise and David Zaig.)

The painting by Frances was “Leah-Rome” which she sold to Ellen Poss. She had started it in 1985 and kept working on it until the last minute. Just before her untimely death she formed a relationship with a scientist. She seemed to have reached real happiness. I’m so pleased that you acquired a painting (“Purple Gloxinia”) for the MFA.

TS When my wife and I were in Rome she was spending a year there at The American Academy and we got to know her well.

CG You talk about that two-year window of collecting for the MFA. How did that come about? You expanded your portfolio from Heade to Kiefer.

TS My introduction to art started 1960-1965 with Robert Neuman (1926-2015), Albert Alcalay (1917-2008), and Pace Gallery which Arnie Glimcher started (on Newbury Street) in Boston in the 1960s. That’s when I was attending Harvard Law School. I immediately met these painters. I still like the work of Bob Neuman who is a very underrated Boston painter. The sculptor Mirko was also at Harvard.

I had background and enthusiasm in the contemporary field. I had worked with Bill Lane which was all modern art. There was a lot of pressure on Jan Fontein that the contemporary program wasn’t going anywhere. At some point he asked me to take it over. I’m glad I did it but I regret that Ken Moffett (1934-2016) was treated badly by the MFA.

CG Not just the MFA. There was a lot of concern about the contemporary program from the Boston art world. Pam Allara, a Brandeis professor and critic, made harsh public statements.

TS It’s a shame as Ken was a very decent guy. He shouldn’t have been in the job to start with.

CG Was he forced out?

TS Oh yes. So, there I was and John Walsh had left (to head the Getty Museum). What you should ask me is “Where did you get the money to buy Warhol and Kiefer?” When Walsh left, I became head of the paintings department. European and American painting were in one department. Then I also became head of contemporary art. So, it was at my discretion how to spend the acquisitions money for paintings. I spent it to get the best for the museum. On Kiefer, Gerhard Richter (B. 1932), Francesco Clemente (B. 1952), Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2015). I bought a great Joseph Stella (1877-1946) of the “Brooklyn Bridge,” Warhol, Alice Neel (1900-1984) “Linda Nochlin and Her Daughter Daisy.” I acquired works by California artists like Joan Brown (1938-1990) and Robert Hudson (B. 1938).

CG Can we talk about the museum’s politics at that time. There was a lot of pressure on Jan Fontein and dissatisfaction with his overall performance and administrative skills. There was talk of a tearful breakdown during a trustee’s meeting. That’s second hand information. When I did an interview with him in 1984, he was then 59-years-of age. He was surprised when I asked his plans after retirement two years from then. He wanted to know where I heard that?

In fact, he was gone three years later. I heard that the plan was for Jan to be forced out and that Walsh would become director. It came as a surprise when Walsh departed for the Getty. So, arguably, Jan survived a bit longer.

Fontein left earlier than he could or should have. There seem to be a couple of reasons in play. Often museum directors leave after completing major brick and mortar projects, acquisitions, or programming. That also occurs when directors loose the confidence of curators and trustees. There was an undercurrent that shortened Jan’s time and then a revolt of curators that quickly routed Merrill Rueppel who followed. When Walsh went to the Getty, Clementine Brown (MFA PR) said to me, “He’ll be back in a couple of years.” If he could be MFA director why would he want to go to the Getty? Walsh was the presumptive heir at the MFA and that was a lot of pressure on Fontein.

TS That’s quite accurate. John was a very attractive, well-spoken guy. He was well liked and respected. He did good shows, Chardin, and others at the MFA. He was talked about as the future director. There was no question about that. That must have made Jan nervous, though he was a pretty secure guy. Everyone assumed that Jan would leave in a year or so and that John would become director. Then he suddenly left for the Getty which, arguably, is one of the top museum jobs in the world. Yes, Jan might have stayed longer, and surely wanted to but I don’t know any of the inside details. I just don’t know what forced him out.

CG Around that time great pictures by Manet and Cezanne were showing up in the galleries as loans from a private collection. I investigated and found that they were acquired by a Boston billionaire, William I. Koch. They were acquired through his foundation. I pulled the tax records at the charity desk of the attorney general. The documents revealed that Walsh, while an MFA curator, was paid some $25,000 annually as a consultant. That was then equivalent to a third of Fontein’s salary as director. We reported it in coverage for the Patriot Ledger. I called for comment and asked Fontein if he knew of this arrangement? He said that he did which greatly surprised me. By then, Walsh had just been appointed to head the Getty.

TS Fontein did know. That arrangement had to be cleared by the director and Howard Johnson, the chairman of the board. I remember the discussion. They OK’d it. So, you were wrong on that one.

CG What’s your view of that? Isn’t it the job of curators to cultivate and work with collectors?

TS Yes.

CG Was that arrangement ethical?

TS I’m too close to John to have an opinion about that.

CG You say that everyone knew about it.

TS Howard and Jan knew about it. Beyond that I don’t know who knew.

CG You came up in my interview with (art dealer) Mario Diacono. He didn’t speak well of the Boston art world, to which he made few if any sales, but praised your interest and support. (Purchase of a painting by Ross Bleckner.)

TS It’s so sad. One of the great tragedies of Boston is that they missed the boat, not only on Mario, but countless other aspects of modern art; anything made after the Armory Show of 1913. I told Jan, “It’s not too late” this was the early 1980s. “It’s not too late to rectify our position in the modern art world. In that field we are about the 60th or 70th ranked museum in America. It’s embarrassing. For the next decade all of the museum’s acquisition funds should be spent on modern art. He said “OMG. The curators would kill me. The trustees would kill me. I could never do that.”

CG You actually had that conversation?

TS Yes, basically, for the two years when I was in charge, that’s what I did. Then Kathy Halbreich (from MIT’s List Visual Arts Center) was appointed curator of contemporary art, soon followed by Trevor Fairbrother. They didn’t have the funds I had and Jan didn’t make the effort to get it for them.

CG You said that Jan was helpful to you in terms of acquisitions.

TS He loved objects. He liked people. He loved collecting. The director is all powerful. If he doesn’t like your proposal it’s dead in the water. It doesn’t go to the trustees unless the director approves. Jan approved everything I proposed. He understood it and wasn’t just rubber stamping. With Lane I said “I’ve got this great collector who I’ve visited a couple of times. He’s been badly hurt by the museum and needs to know we’re serious.” A month later I drove Jan and Howard Johnson out to Bill Lane’s house. We came hat in hand to say that we were sorry about that happened before. We’re here to say we love you and we love your collection. Jan was an active guy.

CG Of the 400 works you acquired how many were from Lane?

TS The Lane collection included a hundred works.

There are only two reasons to acquire something. You’re adding to strength or filling in gaps. You always use one of those two arguments when trying to persuade the trustees. I tried to do both.

You criticized acquiring Benson, Tarbell and those people. They were Brahmins without a doubt but they could produce. Three quarters of their paintings are pretty bad paintings. I was after the top five percent and the MFA didn’t have their very best work. I felt it was my duty to acquire them. Some we got through gifts. Some we purchased.

CG If they were the best Boston artists of their generation why would you not extend collecting to the next generation?

TS We already had that discussion. I don’t know. We already talked about that.

CG You’re not going to budge.

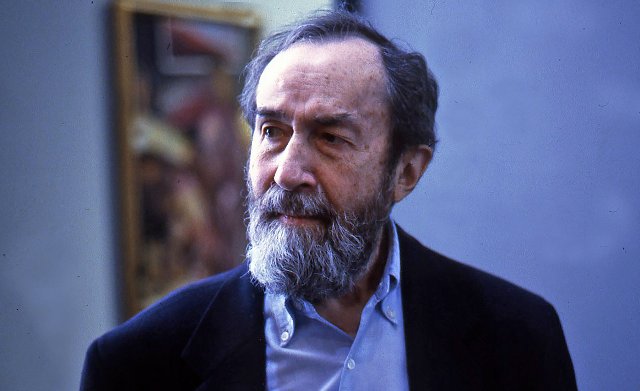

TS No. I would like to please you but I would do the same again. Someone like Hyman Bloom doesn’t have the national or international legs. He doesn’t have the grandeur of a great artist. He literally lays out everything in front of your eyes. What the art world is looking for is subtlety and abstraction. Complexity. With Bloom it’s very interesting, beautiful and powerful. But he doesn’t leave anything to the imagination. He seems to me to be a follower of Soutine, and not a modernist in any way. He didn’t grow over the years. You and I just see that differently. I admire the paintings but don’t see them as deserving of a national or international reputation.

If you go to Chicago you will see a whole gallery of Ivan Le Lorraine Albright (1897 –1983). He’s sort of Chicago’s Hyman Bloom. He’s a better painter and deserves to have paintings on view at the Museum of Modern Art. Bloom doesn’t quite reach that level in my view. That’s how I see it.

CG We’re beating a dead horse. But Boston (particularly the MFA) dropped the ball on supporting its (post war) artists. Period. Bloom’s reputation today would be different if the MFA and ICA did more to support its artists. There were some Bloom and Boston expressionist shows from the ICA of Stephen Prokopoff, to DeCordova, Danforth Museum, and Fuller Museum of Art.

If major institutions provide limited support for Boston's artists how can we expect museums beyond the city limits to take an interest?

TS Not it wouldn’t. MoMA gave Bloom every chance in the world. They showed him in 1942. He was shown at the Venice Biennale. The art world goes to Venice and they all saw the work. There were traveling retrospectives in the 1950s and not enough people saluted. In Boston or out of Boston. Bloom had every chance. He wasn’t neglected but not enough people reacted.

CG I appreciate your point of view and am grateful for the opportunity to talk with you. I enjoy the push back. There are few opportunities to engage with someone with knowledge and passion. Too few even care.

TS But you care and I care so it is a pleasure.

CG I delight in this opportunity and the insights are invaluable.

Let’s turn our attention to the relationship between the MFA and ICA. In the 1950s, when Thomas Messer was director of the ICA, there was a plan to merge with the MFA as a department of modern/ cotemporary art. Messer would become an MFA curator. In fact, he advised on some acquisitions which have held up well. This is discussed in an Archives of American Art interview between Messer and Bob Brown who then headed an AAA office on Beacon Hill. Rathbone killed that.

TS This comes up every decade or two. I’m sure that Rathbone killed it for a whole variety of reasons we could talk about. Boston is a richer place with both institutions. You can’t attach a small adventurous institution onto a larger cumbersome one. It doesn’t work. It’s better that they didn’t combine. Look at what Jill Medvedow has accomplished.

CG I’ve heard those arguments and disagree with them. There are two points. The ICA after Messer, then Sue Thurman, for a time nearly perished. Since the 1960s there were instances of triage. For a small enterprise it was a chronic overachiever but there was a constant struggle to survive.

Had the merger gone through the MFA would have had a strong modernist program a generation before launching one in 1971. The few acquisitions that Messer was involved with give a glimpse of what might have been.

Rathbone insisted on being his own curator which was hit and miss for modern art and mostly miss for contemporary art. Because he knew Max Beckmann (1884-1950) he had a taste for German expressionism. Despite the fact that Perry was treated badly, and ousted by the trustees, he donated his Beckmann portrait to the MFA, as did curator Hanns Swarzenski, the portrait that Beckmann painted of him.

(In 1946, Beckmann painted a double portrait of Curt Valentin, an art dealer who directed the Buchholz Gallery in New York, and Hanns Swarzenski. Upon Valentin's death in 1954 it passed to Dr. Swarzenski who gave it to the MFA.)

In general, particularly the Busch Reisinger Museum, and what (James Sachs) Plaut and Messer showed, Boston’s taste was for Northern European art.

Moffett was appointed in 1971. I quote you as telling me in the 1970s that “The MFA recognizes 20th century art now that it’s almost over.” Do you recall saying that?

TS No, but it sounds so good you can keep quoting me.

CG You worked with David Ross on the Binational. It was a rare instance when the MFA and ICA collaborated.

(In 1988 the MFA and ICA jointly presented The BiNational: Art of the Late '80s in cooperation with the Stadtische Kunsthalle and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen of Dusseldorf and with support from the Mass. Council on the Arts and Humanities, AT&T Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The multi-venue exhibitions presented emerging American and German artists. The MFA team included Stebbins and Trevor Fairbrother. David Ross, Elizabeth Sussman, and David Joselit comprised the ICA’s.)

TS I don’t remember it in detail but it was an extraordinary experience. David Ross was a totally fun, charismatic person to work with. He connected us with an excellent German team headed by Jurgen Harten. Later, he had a Pollock/ Siqueiros show and I persuaded him to add (photographer) Edward Weston (1886-1958). I sent a selection(from the Lane collection) and they fit in beautifully with the abstract painters.

CG Let’s talk about Pollock’s “Troubled Queen” (1945, acquired 1984).

TS I saw it in a gallery I had never been to before (Stephen Hahn). I thought that’s an ugly, powerful, important painting.

CG When “Lavender Mist” was turned down Ken later bought a smaller drip painting (“Number 10” 1949) which he maintained was a very good Pollock.

TS Yes, but it was not great enough by itself to show a major American artist. Here was a 1945 painting with a bit of drip in it and two anguished figures. I had to have it. That really enriched the collection and linked Pollock to earlier expressionist painters.

It’s a powerful painting. I remember when I showed it to Jack Gardner, an old trustee at the MFA. He said “Will it last?” I said, “Mr. Gardner, do you mean physically, its materials, or do you mean aesthetically?” He meant both.

“Number 10” was not great enough by itself to show a great American artist. "Troubled Queen" was a 1945 painting with a bit of drip in it and two anguished figures. I had to have it. That painting really enriched the collection and linked Pollock to earlier expressionist painters.

CG I recall being shocked when it just showed up hanging in the museum. I wondered where it came from. The wall label read “Charles H. Bayley Picture and Painting Fund and Gift of Mrs. Albert J. Beveridge and Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, by exchange.” In exchange for what I wondered?

(By exchange, 28 November, 1984, with Stephen Hahn Gallery: Two works by Pierre Auguste Renoir; “Young Girl Reading” 16 x13” and “A Woman with Black Hair” pastel on paper, 23 x 18” and Claude Monet’s painting from 1884, “Autumn Scene” 24 x 29.”)

TS The Globe wrote an editorial criticizing the purchase. It was the only time I got bad press but the art world applauded.

CG I was at the Patriot Ledger where my editor, Jon Lehman, and I were about to post the Pollock story. We got a call from Clementine Brown (PR director for the MFA). In a friendly manner she said “Charlie, I heard that you have been poking around. What are you up to?” Jon nodded that we should ask her for confirmation of the deaccessions we had uncovered. She said she would get back to us so we waited to hear from her. The Ledger is an afternoon paper and we missed the deadline waiting for her call.

The next morning the story ran in the Globe. She had betrayed years of trust working together. We ran a second-day story. That Sunday, the Globe posted the editorial you were mentioned in. They acknowledged that it had been a Patriot Ledger story.

Later Clementine apologized saying that Jan stood over her and insisted that she make the call. It was sure spite. After that I never trusted her for fact checking on stories. That’s a normal journalistic practice with breaking news.

TS Damn. You should have called me. We had sixteen Renoirs and that picture was never shown. To me, the one I sold was the least of them. Actually, it was a great trade.

CG At the time the question that I asked was about trading apples for oranges. In this case, French impressionism, for American abstract expressionism. Is that kosher?

TS Of course. Why not? They are all paintings. I would have traded a Chinese painting if I could have laid my hands on one.

CG (laughing) Boy it’s fun to talk to you. On your watch did you have a relationship with Barry Gaither.

TS Some. I always respected him. I went there.

CG National Center of Afro-American Artists on Elm Hill Avenue in Roxbury.

TS Yes.

CG In addition to important exhibitions Barry also made acquisitions including important Boston, African American artists. Did you ever visit Alan Crite (1910-2007)?

TS No. I knew about his work, Boston street scenes. I thought it was interesting but not MFA quality, top ranked art.

CG Of course a lot of work has now come with the Axelrod collection.

(In 2011 sixty-seven works by African American artists were acquired from collector John Axelrod, an MFA Honorary Overseer. Overall, he has donated and sold to the museum some 700 objects. The purchase includes works by almost every major African American artist working during the past century and a half. It was made possible with the support of Axelrod and the MFA’s Frank B. Bemis Fund and Charles H. Bayley Fund. Axelrod has also donated his extensive research library of books about African American artists as well as funds to support scholarships.)

You were involved in negotiations to retain a half stewardship of the Gilbert Stuart portraits of George and Martha Washington.

TS I’m glad you asked about that. I had just arrived at the MFA and learned a couple of years before the Athenaeum asked if the MFA would mind if they sold George and Martha? (They had been a long-term loan to the MFA.) John Coolidge, who was then president of the museum, said, “No, we don’t mind.” I got there and they were about to sell them to the National Portrait Gallery. I said “This is outrageous. They’re Boston treasures.” They had been purchased for Boston by something called The George Washington Trust. It was illegal, outrageous, immoral, and unwise. I created a huge ruckus. Half of the Athenaeum trustees were also MFA trustees. It was a very hard battle to fight.

CG You have earned your art combat medals and wear them well.