The New York Philharmonic Blasts Off at Avery Fisher

Alan Gilbert Gives Us Horns

By: Susan Hall - Jun 21, 2010

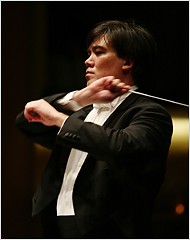

Alan Gilbert, Conductor

Hakan Hardenberger, Trumpet

Wagner, Siegfried Idyll

HK Gruber, Aerial

Mozart, Symphony No. 25 in G Minor

Wagner, Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan and Isolde

The New York Philharmonic

June 19, 2010

This was penultimate performance of the New York Philharmonic’s season, its first under the direction of Alan Gilbert and one that has been universally acclaimed. Now Wagner, Gruber and Mozart. What a delicious prospect.

While conductor Gilbert writes that this is a Vienna-inspired program, it is just as surely a horn evening. The centerpiece, Aerial, is a trumpet concerto by HK Gruber, composed for a trumpeter Hakan Hardenberger.

The program opened and closed with Wagner. While Siegfried has many leitmotifs, who can listen to the Siegfried Idyll without hearing Siegfried’s signature song played on the horn as Siegfried begins yet another exuberant adventure? John Williams in his Star Wars scores was inspired by Wagner’s heroic melodies often carried by the brass.

Only in the 17th century did the trumpet begin to have lyrical lines. Wagner was captivated by brass. In Tannhauser he brought on 12 extra trumpets for the march. Four trumpets herald the king in Lohengrin. Wagner gave an enormous impetus to use brass for tone and color.

The Siegfried Idyll is a well-known gift from Wagner to his longtime love and new wife Cosima, and many women are as envious as I am of this extraordinary present. Sitting in the Hall, Gilbert made it easy to imagine waking one morning to these evocative and yes, loving, phrases, a set up for not only a perfect day, but a perfect life. Wagner often suggested such feelings belonged in a world other than ours, but Gilbert was not content to give up big feelings to the future. He drew out the orchestra so we had them in the here and now. When the horns were featured, they were particularly beautiful.

Wagner imagined the trumpet in the Ring as of Brobdingnagian length and tone color, extending from the bottom notes of the tenor trombone to the topmost notes of the French horn. The instrument would be 23 feet long, the lower notes of poor quality and the upper notes unplayable by human lips. This instrument was dumped and one closer to the C trumpet Hardenberger brought onto the stage was devised. Of course, Hardenberger’s own Brobdingnagian aspirations pushed the composer Gruber and may have made three horns necessary to perform Aerial.

Hakan Hardenberger entered with a trumpet in C, a piccolo trumpet and a cow horn. Although the composer describes the first movement as a view of Nordic landscapes and the northern lights, and the second as a pullback to the whole earth, the first movement is more ethereal. It is musically more distant, quieter and flowing. The second movement, which is connected without a break, is a wild, noisy description of a world full of life and very present. Aerial delights with the improvisational suggestion of jazz, and rhythms of the dance. Hardenberger, announcing that no challenge will deter him, actually sings into his instrument.

The short curved cow horn was warm and inviting, and makes it easy to see how a composer like Ligeti could move on to car horns. The horn is an important sound all around us, on earth and elsewhere.

At the World Cup in South Africa, the vuvuzela, a plastic trumpet, is continuously heard blaring out in the stands. Organizers would have done well to bring in Hardenberger and his C trumpet for some special moments.

With Father’s Day following, we heard a brisk, deep version of Mozart’s Symphony No. 25. Mozart’s father, Leopold, had written his own trumpet concerto, but their trip to Vienna, which immediately preceded the composition of this piece, liberated the son from the sway of the past. Horns again come into play. There are an unusual four horns, double the number conventionally used in classical symphonies.

The program ended with the Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan and Isolde. While some complain that Gilbert does not bring sufficient emotion to pieces like Wagner’s, they are mistaking conductors' ballets for musical passion. Certain conductors wave their bodies instead of their batons. Gilbert is a more thoughtful and deliberate conductor who works hard to draw out all the color and depth in pieces like the Liebestod. He and the orchestra succeed.

Simulation of the sex act is not conducting. As listeners we are not deceived by faux passion choreographed. While perpetual-motion conductors seem more inspired by Elvis than Wagner, they don’t display Elvis’s musical sense. Gilbert clearly does, although he choses not to make emotional display the center of any evening. He is about passion in the music.

With Tristan, of course, Wagner announces that large feelings are not of the world. You have to die to experience them. As conducted by Gilbert, the music certainly was to die for.

The last series of the season is on June 23, 24, and June 26. Magnus Lindberg, New Work and Beethoven, Missa Solemnis.