Thoughts on Provincetown Artist Edwin Dickinson

Publishing Off and Online

By: John L. Ward - Jun 25, 2010

Prompted by a report from my publisher indicating dismayingly sparse sales, I recently began checking to find out what awareness presently exists of my book, Edwin Dickinson, A Critical History of His Paintings, and of the artist himself. I retired the year my book came out (It first appeared December 2003, but it seems that most copies have a publication date of 2004), and I haven't paid much attention to art writing ever since (I have been doing Balkan folk dances, managing my meager investments, and reading all of the novels I hadn't time for when I taught art history and painting).

I discovered that the internet was acquainted with my book: writing my name and Dickinson's in a search box produced a page of entries advertising it, some with pages of my text available online, but there was little evidence that people had actually read it, other than the writer of "All things Edwin Dickinson", one professor who put it on a list of texts to buy, and one writer who quoted a brief observation about Dickinson's prints. I found a few good pieces in my present online search--particularly David Carbone's review of the 2002 retrospective--but in other places a dismaying ignorance, both of my book and of Dickinson. I was delighted to discover the Berkshire Fine Arts and Painting Perceptions websites.

It's ironic that the one person to review my book at Amazon.com, a painter, complained about the few color reproductions (only seven pages, he said, whereas there are actually sixteen, counting both sides, with nineteen images) and said the book wasn't good for research, evidently meaning that there weren't many color images to look at.

That hurt, since I am a painter as well as an art historian and have always tried to write about art in ways that artists could relate to while also researching my subject as carefully as possible.

The fact is, without the willingness of my university to cover the costs, I couldn't have afforded to publish the book at all, much less include any color pictures. It took more than a year, with about eight revisions, to get the Chinese company making the color reproductions to get the color right, and although still not perfect, they are of a fairly consistent quality (in comparison with those in the Edwin Dickinson, Dreams and Realities catalogue, done in Japan, which range from excellent [plate 16] to horrible [plates 20, 21 23, 29, 53]. Others look very good [24, 40], but I can't evaluate them precisely because I didn't take color notes on the paintings when I saw them).

By being linked to a major, touring exhibition that exposed audiences to the work and backed by grants from foundations and public money, the catalogue was able to include many more reproductions than mine. As the chair of the editorial board that agreed to publish my book explained in his acceptance letter, "because of cutbacks by the trade book market and other financial restraints felt throughout the publishing business generally, university presses are experiencing dramatically increased pressures to publish books beyond the usual scholarly monograph. This makes for an unusually competitive situation. Your book represents a scholarly achievement of the highest order . . ." One of my colleagues said, after speaking to someone from our university press, "What they really want to publish are travel books and cook books."

I had hoped to finish the book by the date of the retrospective exhibition, and my text was essentially complete by that time. But proofreading the text with a copy editor and again after it was printed, assembling an extensive index, and getting the photos right meant a delay of over a year. Except for the assistance of the copy editor, I had to do almost everything myself, including designing the dust jacket. Consequently, I had not seen the catalogue for the 2002 retrospective before my text was finished except for editing. When I finally had a chance to read it, I was pleased to find that the two publications largely compliment each other in their approach rather than covering the same ground.

Another difficulty with publishing color photographs of art works in a book or with getting a book published at all on an artist not known to the general public is that readers tend to buy books on artists they know something about.

Unfortunately, although Dickinson's works are owned by many of the most important museums in the country, few of them are shown with any regularity. In the 30 museums and galleries that I visited to see Dickinson paintings, drawing, and prints during the eight years I worked on the book, the only ones where I saw any Dickinsons on display for the general public were the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (sometimes with two paintings), the Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester and the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco (each with one painting), and possibly the Arkansas Art Center (I saw the eight Dickinson drawings in the collection; I think one of them was on public exhibition at the time). To my surprise, Dickinson's early painting, Days Lumberyard in Winter, a wonderful little painting owned by the Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska, but not there when I visited, turned up in a show virtually in my back yard at the Harn Museum of Art in Gainesville, Florida.

I had the cooperation of Dickinson's daughter, Helen Dickinson Baldwin, in writing my book. She has done many years of research on her father with the goal of publishing a catalogue raisonné of his work. She gave me a lot of information, explained matters I had misunderstood, and corrected errors I had made. She was not always happy with my interpretations of her father's work, and she required me to delete information about the violent deaths of a couple who were patrons and close friends of the Dickinsons. And she objected to an observation I made about his brother, which, based on a brief reminiscence in his journal in his later years, I still believe to be correct.

On balance, that was a small price to pay for the many pages of helpful comments and information she gave me. But made me aware that censorship is one of the problems one can encounter when relying on the assistance of an artist's family. (Or an artist: one of the painters in my book American Realist Painters, 1945-1960, insisted on knowing what I proposed to write about him, then decided he didn't want me to write about him at all and said he would sue me if I did. Fortunately, his dealer intervened and told me to go ahead).

In checking on the present state of Dickinson research, I discovered that there was only a bare bones article on him in Wikipedia, including a biography that skipped over his entire active period as a professional artist and contained only three sentences on his art! So I have been writing an article designed to give him the attention he deserves--and with the hope that it would make my book (which I am citing in copious notes) better known. A major Dickinson collector called today to tell me that, although he was aware of it, he had only now bought the book and begun to read it.

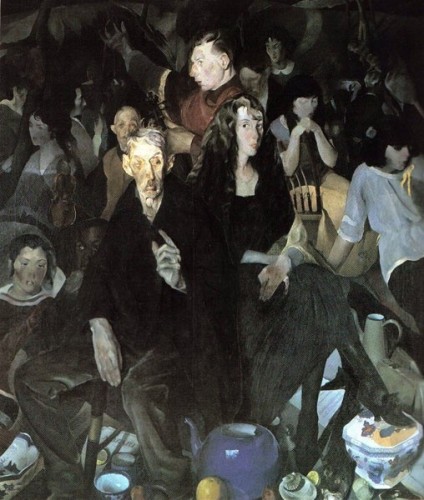

My hope is that other Dickinson fans will assist with obtaining illustrations for the Wikipedia article after I put it online. I understand this is possible under the fair usage rule to the extent that the pictures are discussed--assuming images are available--but I won't have time to put in the effort to locate images and write justifications for fair use status. I must hope that there are interested, willing persons with more expertise in doing this than I have. Finishing my already rather extensive text is as much as I am able to undertake. I had intended it to be much more laconic, but after I had written an essay of a few pages, I realized that I couldn't do Dickinson justice without discussing his major works individually.

I would be most grateful for any assistance in getting pictures for my article. (I notice that the Dickinson images I see online are often quite unreliable in color or value range. In light of this, and the criticism my book received for having too few color pictures. I should mention that Dickinson disliked having his work reproduced in color, which he found to be often inaccurate. In 1940 he wrote that he hated a color photograph; in 1957, 1965, and twice in 1969 he refused to have color photographs of his paintings published, observing on one occasion that "color reproduction is in its diapers;” and in 1968 he found fault with the color reproduction of his painting South Welfleet Inn in the catalogue of the Venice biennale.

I suspect that he would also have been dissatisfied with the reproduction of this painting in the catalogue of the 2002 Dreams and Realities show, which, although far from the worst reproduction on the catalogue, has, according to color notes I wrote while comparing the reproduction with the actual painting, too much contrast and exaggerated color intensity. In the present situation, however, given the low fidelity of many of the images of Dickinson paintings I have seen on line, I would be delighted with pictures of this quality and grateful for almost any Dickinson pictures someone can come up with.