Patricia Hills on American Art

Whitney Museum Curator and Boston University Professor

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 25, 2019

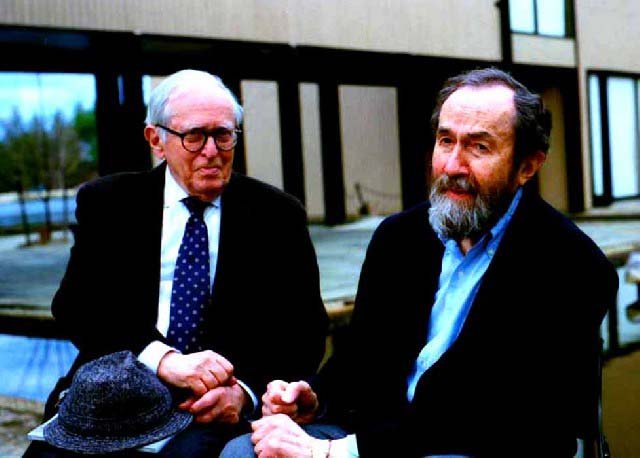

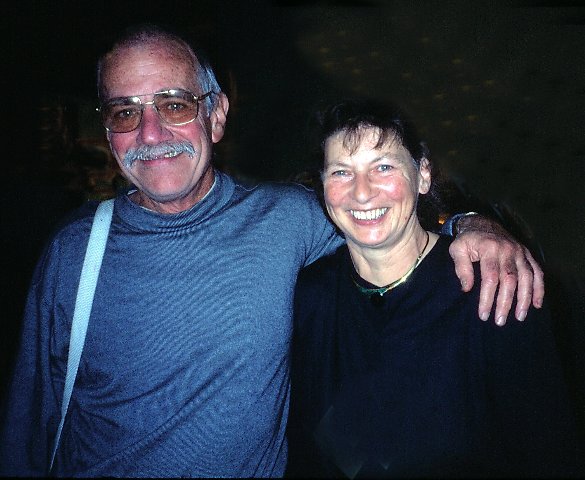

Several years ago Patricia Hills, and her husband Kevin, relocated from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Brooklyn, New York. The move entailed being closer to their family. I earned a Master's Degree under her supervision at Boston University. Through journalism, as columnists for Art New England, we interacted and discussed exhibitions and developments in the Boston arts community. Often there were sharp differences of opinon as well as a shared passion for American art, past and present.

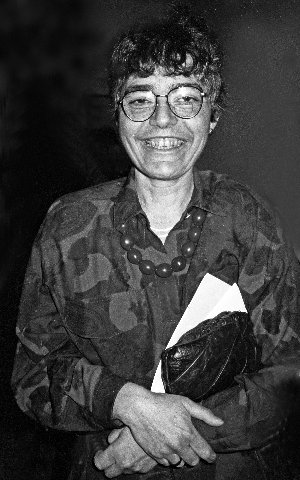

The interview that follows was very much a joint effort. The transcribed text was sent to her for accuracy and fact checking. While sticking to the initial conversation it was enhanced and embelished by both of us. It is a summary of her distinguished career as a scholar, curator, critic and professor. Now retired she has returned to research on the 19th century artist, Eastman Johnson, who was the topic of her dissertation. It took some persuasion to publish the first book on Alice Neel but now there are many. Encouraged by Harvard professor, Henry Gates, she wrote a book about the African American artist, Jacob Lawrence.

As a woman, Marxist, and American art scholar she is frank about challenges and conflicts. Initially denied tenure, but supported by BU president John Silber, that decision was overturned. That year, Hills was the only BU professor to earn a Guggenheim fellowship. She also discussed being sabotaged when organizing a John Singer Sargent exhibition for the Whitney Museum of American Art. That project was delayed for three years.

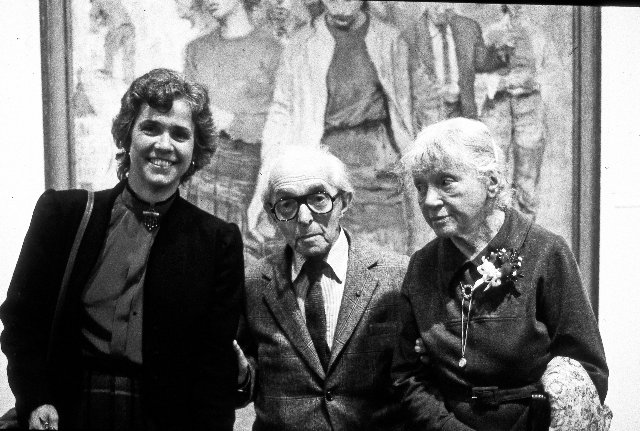

With graduate students-Amy Lighthill, Pat Johnston, and John Stomberg- she was director of the Boston University Art Gallery. That entailed working with Boston and Northampton artists as well as memorable exhibitions of Alice Neel and Raphael Soyer.

Charles Giuliano Your dissertation was on Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) for the New York University Institute of Fine Arts. Recently you got a grant to work on his catalogue raisonné.

Patricia Hills I got my PhD in Fine Arts at The Institute in 1973. My thesis focused on his genre painting. He was also a portrait painter. At the time there was not a lot of work on Johnson and he was missing from the pantheon of 19th century American painters. He falls between William Sidney Mount (1807-1868) and Winslow Homer. Mount was born much earlier and Homer was born in 1836. Eakins was not born until 1845.

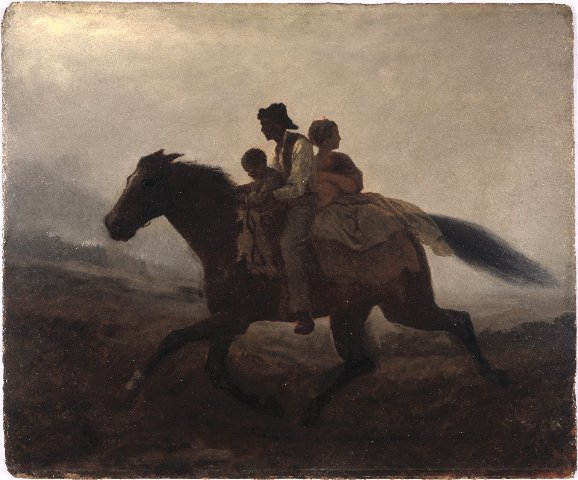

When I was doing preliminary work it seemed that Johnson was the link between Mount, and the art of everyday life, and the newer painting which was much more painterly. The impressionism you see in Homer and later artists. Johnson did a great number of pictures of African Americans when they were enslaved and later when they got their freedom. At the time he was well known for his images of African Americans.

CG Ones that I recall are “The Freedom Ride.”

PH He did three versions of that subject. One is at the Brooklyn Museum and another is at the Richmond Museum of Fine Arts.

CG Earlier he had painted “My Old Kentucky Home.”

PH The actual title is “Negro Life at the South.” The Stephen Foster song came after it was painted and for a reason I have never been able to figure out a number of people gave it that name. It has nothing to do with Kentucky. It’s the back yard of a townhouse that was based on his father’s in Washington D.C. Slavery was very alive and well in Washington through the Civil War until Emancipation.

CG When did you retire from BU and now have time to focus on the Johnson project?

PH When I defended my dissertation in 1973 I had started at the Whitney Museum as a curator. In 1974 I took a full time teaching job but continued my work at the Whitney. I continued as an adjunct curator until 1986. We moved to Boston in 1978 shortly after the birth of our son Andrew. We brought other kids and my mother. It taught at BU until the end of June, 2014. I am now professor emerita from BU. We moved to Brooklyn, New York two years later. I’m not teaching but am involved in a lot of projects one of which is to complete the catalogue raisonné of Eastman Johnson. My assistant and I have been working on this for a long time. I never intended to but I got more and more information on index cards. It got to the point where it was time to put it onto a data base and that’s what my assistant has been doing for the past five or six years.

I got a small grant from the Andrew Wyeth foundation for $10,000 and that helped to pay for my assistant Abigael MacGibeny. I got the grant through BU but the project needed more money. The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation, of which Warren Adelson is president, granted me money through my sponsoring institution, the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown. Warren has been a patron of the art history department of BU for many years.

At one point Warren Adelson said to me “Pat I would like to give the BU department some money. What would you do with it?” I said I would set up scholarships for students of American art. He gave us money and then the Horowitz Foundation also gave us money. I was bringing in so much money that the president of BU said “Don’t talk to Warren Adelson any more. We’re going to handle it from now on.” At that point the Horowitz Foundation gave BU $1.5 million dollars for the department to set up a visiting professorship. It’s for one semester in American art. It’s to bring someone doing something in American art that the current professor is not doing. I believe the current visiting professor works with Native American art and indigenous peoples.

The grant I got was for $186,000. That allowed us to hire Panopticon to migrate our data to their data base and set up an interactive website. We hope to have that done in two years. It also allows Abigael to increase her hours considerably. It also gives me a small salary which I never had before. I can pay for travel and not take it out of my own pocket. I know a lot about Johnson and want to share it. I don’t want to go to my grave being the only person who knows about Eastman Johnson.

CG That’s a factor in this interview which will be a chapter in my next book “Boston Fine Arts.” There is a lot of primary source material that I am trying to document while it is still possible. I understand that your Johnson project will be on line and not hard copy.

PH That’s right, but people are advising me that it is important to have some hard copy version as well. My dream is that it appeals to a kid going to junior college in New Jersey who is interested in images about African Americans in 1863. That student can go on line and see them. Johnson did several dozen pictures of African Americans. He painted in a way that showed much more empathy to black people although he’s locked into a 19th century sensibility. There’s never a caricature.

CG You’ve done Johnson exhibitions and I have a book on him that you published. What’s the history of his exhibitions and publications?

PH The first major exhibition was in 1940. It was curated by John Baur for the Brooklyn Museum. Later he was director of the Whitney. I knew how to do an exhibition, since I had been a curatorial assistant at MoMA. When I was doing my dissertation I went to Baur and proposed my doing an Eastman Johnson exhibition. He was delighted. In 1972 we did the Eastman Johnson exhibition. I was a guest curator, and right after that I was hired as a curator. That show traveled.

Time went by and there were some smaller exhibitions. One was on the cranberry pickers and another one on his maple sugar camps. In 1999 the Brooklyn Museum did an exhibition which was a bigger show with a bigger catalogue. The curator was Teresa Carbone, and I was a co curator. She spent three days looking through my files and finding the locations of all these works. I knew where they were.

Since then there hasn’t been anything. He’s been included in exhibitions on the Civil War and ones on genre painting. I would like to see a couple more exhibitions. As I travel tracking things down I’m suggesting to curators that they might do another exhibition. Perhaps one on Nantucket. There are a lot of possibilities.

CG At this point how many works have been identified?

PH That’s a good question. When John Baur did his show in 1940 he came up with a list of 472 works that was included in the catalogue. I built on that and we are now up to about 1500. That’s been my work tracking down things in museums and with private collectors, and going to The Frick Art Reference Library, which has a lot of photos. I’ve been at this, Charles, for almost 50 years.

CG We were at the Cape Cod Museum of Art a couple of years ago and encountered three pencil portraits in oval frames.

PH Of women, right? He did beautiful portrait drawings before he went to Europe. He was the best portrait draughtsman in the 1840s. I know the ones you saw. He did beautiful drawings of the Longfellow family, Charles Sumner, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. They are really gorgeous portraits. He really wanted to learn how to be a painter so he went to study in Düsseldorf in 1849. He was two years in Düsseldorf, mostly in the studio of Emmanuel Leutze who is best known for “Washington Crossing the Delaware.”

Then he went to The Hague to study the portraits of Rembrandt by making copies. He developed a career there painting portraits. Then he studied briefly with Thomas Couture in Paris. Couture was a famous teacher of American artists, and Édouard Manet studied with him.

CG If they come to market what’s the current price for a Johnson?

PH Most of the paintings are small and genre subjects may sell for $300,000. They have gone up to almost a million. The market is very weak now for 19th century American painters. Everybody wants to buy contemporary art.

CG That raises the controversy provoked by an attempt of the Berkshire Museum to sell works from their collection. Auction results in some lots did not reach estimates. They had to sell additional works to reach their goal of $50 million.

PH These things go in waves and perhaps higher evaluations will come back. A first rate Johnson sells for a lot of money while a minor work, or portrait of an unidentified individual, may sell for as little as $5,000.

CG Overall, what is the market and intellectual/ critical benchmark for 19th century American art?

PH There is a great deal of interest in artists who painted African Americans or Native Americans. There’s a lot of debate about that. Some people will say that a Johnson painting is sympathetic while others will say that it’s demeaning. For the past twenty years there has been controversy when white artists paint pictures of African Americans. As I said, Johnson never caricatured a black subject.

CG Where would George Catlin, Charles Bird King and Seth Eastman come into this debate as artists who depicted Native Americans?

PH People are grateful for those pictures. Seth Eastman sometimes would paint savage Indians. There is an image by him of an Indian gleefully holding a scalp in (Henry) Schoolcraft’s publication. [In 1846 he was commissioned by Congress for a major study, “Indian Tribes of the United States,” which was published in six volumes from 1851 to 1857. Eastman’s second wife was so enraged when she read “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that she wrote an anti “Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Mary Howard was from a slaveholding family in South Carolina. In 1860 she published the bestselling “The Black Gauntlet.”]

CG The paintings of John Mix Stanley appear to have a romantic view as do the novels of James Fenimore Cooper or the dime novels of the German, Karl May. It starts with the 1801 novel “Atala, ou Les Amours de deux sauvages dans le desert” by François-René de Chateaubriand. The 18th century writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau popularized the notion of the “noble savage” (outsider, wild human, an "other" who has not been "corrupted" by civilization and representing humanity's innate goodness). There is the “John Wayne” school of Frederick Remington. One of his bronze sculptures decorates the Oval Office.

It appears that these earlier frontier artists were not a part of that.

PH That’s right but I wouldn’t put John Mix Stanley with them. He was an early artist. His paintings are pretty good. There’s Karl Ferdinand Wimar who shows so called “savage Indians.” They were fighting against white people so they were not being savage for the sake of being savage. It’s the later artists like Remington and Charles Russell who make Native Americans look idiotic. Those are the people who feed into racism. There’s a market for those images.

CG What was your sense of the Boston art scene when you came to BU in 1978?

PH They hired me but never intended to give me tenure. Carl Chiaranza [photographer and photography historian] and the history department were great enthusiasts of me. But many people in the art history department were negative toward me.

One of the things that I got saddled with, which turned out to be quite wonderful, was becoming director of the Boston University Art Gallery. I took over from John Arthur whom nobody seemed to like though I did. The studio artists were made to turn the gallery over to the art history department. Because I had experience at the Whitney they gave the job to me. I was teaching full time plus running the BU Art Gallery. I had a baby at home, a bunch of teenagers, plus my mother. I had student helpers like Amy Lighthill [later a curator for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston], Pat Johnston, later John Stomberg [director of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth]. We got involved with the contemporary art scene. It was great, and I learned a lot.

CG Going back to John Arthur he is among the primary curators and writers on American realism. His BU shows focused on the leading artists of that genre. I recall his Philip Pearlstein and Alfred Leslie shows. With curator Ken Moffett of the MFA he organized a memorable Richard Estes exhibition. I recorded an interview with him about the Bicentennial show he organized “America 1976.” It’s in Archives of American Art. (https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/charles-giuliano-sound-recordings-10625

At the time he was a strong advocate of realism. Interest in realism has faded from then to now.

John told me that he suggested to Moffett that they support the exhibition by acquiring an Estes. The answer was that the museum couldn’t afford to. That was both correct and short sighted. Many major museums take pride in owning works by Estes which are also much enjoyed by visitors. Moffett was ecumenical in supporting curatorial projects for work he did not personally endorse. I had that discussion with him during my annual lunch with him many years later at the Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art. During one visit there was a major Nam June Paik show which was light years from his focus on formalism.

PH I continued that programming in part because the BU studio department was so focused on realism. It was an old fashioned, burnt sienna kind of realism.

The first show I organized was for Alice Neel. Years later David Aronson’s wife met me at a party and said “Pat I have been reading your book.” I said “Which one?” She said Alice Neel. I said “Of course you saw the show.” She said “No, I never saw the Alice Neel show. I was told not to bother.” [Aronson chaired the fine arts department of BU]

When Neel came I approached the department to have a professor bring a class down and meet her. The only artist willing to do that was John Wilson. She talked about her art with the students. Later I met another artist who came out of the BU program who recalled that same order “Don’t go to the Alice Neel show. It’s not worth it.”

CG I remember her talk and she looked rather benign, more like Grandma Moses than a radical artist.

PH She had a sweet face and blue eyes.

CG In her slide show she discussed paintings she had done in Harlem. She showed a painting of a nude guy with three penises.

PH Joe Gould. [1933 painting. He was a homeless Harvard graduate and a Greenwich Village eccentric who went from bar-to-bar talking about the book he was writing.]

CG The audience laughed when she commented “He was a hell of a guy.”

PH She was fascinated by men’s penises. She painted a lot of them.

CG At that time you were her champion and later she was widely accepted as a mainstream artist with works in major museum collections.

PH She is now. The estate is represented by Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea. There is a show on right now of her nudes. [Through April 19, 2019] It’s a substantial show and looks really good. I wrote the first real book on her. I pitched it to Abrams three different times. They finally published the book and immediately republished it.

[Checking Amazon, including Hills, there are now 15 books on the artist.]

CG I also recall your Raphael Soyer show. I covered the show and also photographed him at BU as well as in Provincetown. You asked me for images for the BU Gallery archive. You said in a stern manner “Now Charles, please do not describe him as diminutive.” (Both laugh)

Those were off kilter shows at the time which in hindsight were prescient. You also have a bias for art that is left of center. We have had debates about politics vs. aesthetics. That is a part of the discussion of American art.

My former professor of Renaissance studies, Creighton Gilbert, wrote to me when I informed him that I had shifted my graduate studies from Italian Renaissance to American art. He wished me well but stated that one Italian Renaissance artist was more important than a hundred American artists. I responded: what if that artist were Homer or Whistler? Of course after WWII we have Irving Sandler’s “The Triumph of American Art” and Serge Guibault’s “How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.”

PH That was typical.

CG Through your considerable effort, as well as the American Studies program, BU has become a matrix for the study of American art. It hasn’t been easy to overcome traditional art historical bias and can you address that?

PH Exactly. It was my friends in the American Studies department that often supported me. When I came to BU John Kirk was the head of American Studies. He was an iffy supporter of me at the time, but he did eventually come over to my side. His focus was Colonial furniture and he was a major force in the field of American decorative arts. They created a program with internships in museums (and historic homes). So a lot of the American Studies students did dissertations on the fine arts. A lot of that came from relationships with SPNEA now called Historic New England. Keith Morgan headed the program for a long time and he was an architectural historian. There was a strong interest in the fine arts which is not true of a lot of American Studies departments, which traditionally focus on literature and history.

I got involved with the American Studies Association and organized the Visual Culture Caucus, which is still operational.

CG What was your relationship with the Boston arts community?

PH When she was involved with the gallery Amy Lighthill and I made studio visits.

[Amy Lighthill replaced founding curator Kenworth Moffett as curator of contemporary art at the MFA. She was a part of the curatorial team in collaboration with the Institute of Contemporary Art that put together the show Boston Now: Sculpture (the ICA's part)/ Emerging Massachusetts Painters (MFA's) in l984. Ted Stebbins essentially blacklisted her so there were no more shows. She left the MFA in the spring of 1986.]

[Later ICA and MFA curators collaborated with German curators to create the international touring exhibition BiNational in 1988. The MFA director was Jan Fontein and its team included Lighthill and Ted Stebbins, curator of American Art. The ICA team was headed by director David Ross. The German museums were Stadtische Kunsthalle Kunstsammiung Nordrhein-Westfallen and Kunstverein für die Rheiniande und Westfallen, Düsseldorf.]

[There was controversy about how Lighthill left the MFA. Briefly, she was replaced by Kathy Halbreich recruited from MIT, who soon left to head the Walker Art Center. She was replaced by Trevor Fairbrother, another BU alumnus, who was mandated to show works from the museum’s underwhelming collection. He found interesting ways to get around that. Cheryl Brutvan, an underhire, was more willing to do the bidding of MFA director Malcolm Rogers, a generalist and populist. From the hiring of Moffett in 1971 on there has been chronic underachievement for modern and contemporary art at the MFA given its global status. That is expected to change under the current MFA director, Matthew Teitelbaum, who was formerly an ICA curator. But there is much to overcome given a century plus of neglect and misdirection.]

PH At the BU Art Gallery we put on a number of shows of Boston artists. We had shows on landscape and portraiture. John Arthur had done still life so we didn’t do that. We got to know a great number of people. I was on leave one year and Dan Ranalli came on and continued that.

These were show where artists sent in slides from which we scheduled studio visits. We got to know Gregory Gillespie and the people in Western Massachusetts. [Scott Prior, Jane Lund, Randall Diehl, Frances Gillespie] I did a show “Social Concerns in the 1930s” that was followed by “Social Concerns in the 1980s.” We showed the Starn Twins and Greg Amenoff. Later the Danforth Museum under Katherine French started showing a lot of these artists. She was very involved with Boston Expressionism and its legacy. I was also interested in that. [Karl Zerbe, Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and their progeny, David Aronson, Arthur Polonsky, Henry Schwartz, Gerry Bergstein, and Lois Tarlow.]

Boston was always overshadowed by New York. The Starn twins moved there. Overall, I thought it was a lively scene. I liked the fact that you were teaching at BU. We had a lot of our fine arts students taking your courses at night.

CG [Through Metropolitan College, under its fine arts chair Dan Ranalli, I taught modern art and an avant-garde seminar during fall and spring semesters.]

I loved teaching at BU as the kids were so bright. The avant-garde seminar was my favorite course but I found the kids to be very conservative. There were lively debates at the beginning of the semester but by the end they were more receptive. The greatest resistance came from studio majors but theatre students were the most engaged. It was such a privilege to expand their critical thinking. The more they protested the better I liked it. There was such outrage when I showed videos of John Cage, Chris Burden, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Jeff Koons or “Waiting for Godot.” One student was incensed by “Six Characters in Search of an Author” and another was enraged by Jack Kerouac. For me it just set up great debates and teaching moments.

PH That’s how the studio majors were at BU’s School of Fine Arts. Their teachers didn’t like Alice Neel.

CG What confounded me about BU students was how bright they were, but also that they were so rigidly conservative. That was the challenge.

PH I taught an undergraduate course called “Art and Politics.” I would get about 30 students. They were divided into groups of five. They wrote thumbnail bios on index cards, and I put them together. I tried to make compatible groups. I would take strong students and mix them with weaker ones. I mixed, for example, studio and perhaps a philosophy major. They had to produce a work which was aesthetic and political. The best part was that they had to work collaboratively. There were students who just refused. They complained that someone in their group wasn’t doing the work. By the end of the term when they did their projects everyone was happy.

CG The MFA has a group portrait of the Northampton realists by Randall Diehl which you never see. They do display works by Prior and Gillespie’s “Imaginary Pregnancy” a portrait of his wife Peggy. Their relationship was an alleged factor in his suicide. It’s a horrible story. Although they lived in Northampton they are regarded as having a role in the Boston scene. Through Stebbins, and then Lighthill, the MFA took an interest in the work. Gregory showed with Nina Nielsen and Scott with Alpha Gallery.

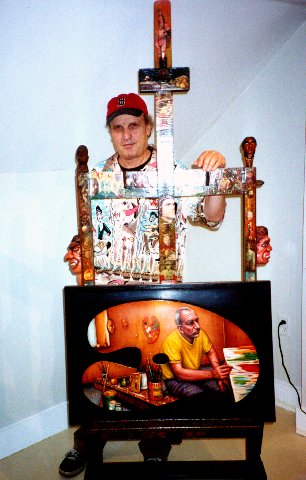

PH Did you have contact with any of those artists? Personally, I did not but Amy Lighthill did. She was good friends and liked to hang out with them. She got an Alice Neel into the MFA collection as well as paintings by Greg and Fran Gillespie. She worked under Ted Stebbins who was clueless about any of this. She made contact with the artists, and they liked her. Because of her I became familiar with those artists. They were offbeat but not like the Hairy Who in Chicago. I liked artists who are kind of kinky.

CG Actually that only applies to Greg who made quirky Bosch-like, fantasy paintings as well as straighter realist portraits and still life paintings. The fantasy paintings didn’t sell and at the time of his death he owed money to Forum Gallery for advances on sales. He was supported by gallerist Bela Kadar but when she died her son had a different attitude. I was working with Nina Nielsen to curate a show of Gillespie’s psychedelic paintings when he died. It was a terrible tragedy which impacted many artist friends.

In interviews with artists and gallerists a question that always come up is why Boston is so undervalued? Reputations for the best Boston artists don’t extend beyond Route 128. As you point out some of the best artists leave. When Stux Gallery for a time had Boston and New York galleries, other than the Starn twins, Stefan had no luck promoting Boston artists although he later tried again with Gerry Bergstein. Alex Grey was unique in establishing himself as a visionary cult artist. Doug Anderson was widely admired but his career imploded because of a devastating Peter Plagens review when he was included in a Whitney Biennial. Overall, it’s been tough sledding for Boston artists to establish national reputations.

PH Henry Schwartz was a major artist.

CG He had a retrospective at the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton, which proved to be his undoing. It caused depression, and he was institutionalized. Arthur Dion of Naga Gallery regularly visited him and continued to support the work.

PH I’m looking at the catalogue of my show “Social Concerns in the 1980s” and it included Alex Grey.

CG For a time he had a gallery in New York and is now in upstate New York. His following has nothing to do with the art world. Paul Laffoley was a major visionary artist with a national and global following. He was with Stux and had a retrospective at The Addison Gallery. He was represented by Kent Gallery in New York but when I showed him at New England School of Art & Design it was his first Boston show since Stux closed. With Joanna Sultan we arranged for a lecture at the Museum School. People came from all over the country to hear him speak including a group of students from Portland School of Art.

It was the nature of Boston to allow for visionaries and eccentrics from William Rimmer to Kahlil Gibran the poet artist, his nephew and namesake a sculptor, and on to Grey and Laffoley.

PH There was David Fichter who did murals with a number of students in Cambridge, like the Middle East Café in Central Square.

CG You were a great supporter of Arnold Trachtman.

PH I didn’t agree with his politics. He was too much of a Trotskyite. When I showed him I got into trouble with the BU administration. Once they froze my salary. I was pissed and tracked it down. Arnie did these pictures of Ronald Reagan. I am looking at the images in my catalogue. He was anti war. They were very strong big pictures.

CG Probably around 1968 Arnie had a show in a Harvard house. It got closed by the university because of its politics. I learned about it through media coverage. I contacted him and went to see the work. I was friends with Drew Hyde who had just become director of the ICA. They had been evicted from New England Life Hall on Newbury Street under director Sue Thurman. In issue 25 of Avatar that summer I wrote a story “ICA on the Run.” The content of the ICA was being stored in its original home on Soldier’s Field Road. It was built under the founding director James Plout. As a teenager, when Thomas Messer was director, I saw an Egon Schiele show there. It was a very funky, loft-like, metal building. The location was inaccessible to public transportation.

I convinced Drew to let me curate a reinstallation of Arnold’s work. We became friends and showed together a couple of times; once in Iowa, and also at Community Church Art Center in Copley Square. Over the years, I wrote about the work and included him in shows I curated. He is now elderly and still at work in Cambridge. He showed with Galatea Fine Art in Boston’s SOWA gallery district in the South End and now with Childs Gallery on Newbury Street.

What’s your take on The Boston Expressionists?

PH There’s been some good writing on it and some not so good writing. When Katherine French was at the Danforth Museum she was really trying to promote it. Everyone acknowledges that it was an important aspect. New York had gone in the direction of emptying out any discernable emotional content in art. There’s that switch that goes from “abstract expressionism” to “the New York school.” With Rothko and Pollock they were trying to express some kind of internal amorphous feelings. The critics began to read it as very abstract and Clement Greenbergish.

In Boston, there was a strong German tradition because of the Busch Reisinger collection, and German music performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and other music societies. There were German overtones in what you saw. Max Beckmann was an influence, and wasn’t Kokoschka in Boston for a year or so?

CG I believe that Kokoschka may have taught briefly at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. What I recall is a semester that might have been summer school in the Berkshires.

[An essay by Nick Capasso states that “In addition to his persuasive pedagogy, (Karl) Zerbe was instrumental in bringing major expressionist artists to the Museum School to lecture and teach. In 1948, Max Beckmann visited the school, where an exhibition was held of his work. While there, he also delivered a talk on humanistic values in art and conducted critiques of students’ work. Zerbe also programmed a Museum School summer session at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which was directed by major expressionist artists: Ben Shahn in 1947, Mitchell Siporin in 1948, and Oskar Kokoschka in 1949.”]

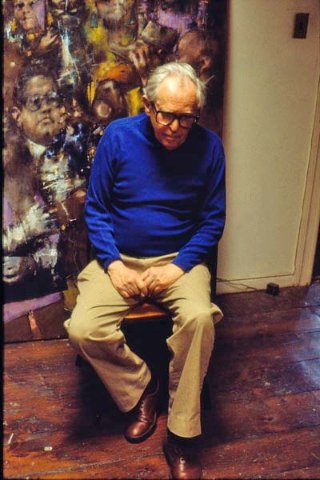

PH That influence lasted and later Philip Guston taught at BU. Although he was a New York artist he fit right in with the idea of expressionism. For a time the best thing about the BU studio program was Guston’s being there.

CG When Guston was visiting Boston, commuting from New York, it’s alleged that he offered to give a painting to the MFA. Apparently, Ken Moffett responded that the museum would take one of his earlier abstract expressionist works. At the time, the mainstream art world had mixed responses to his figurative direction. They could have had the pick of the studio. Later, when prices escalated, they acquired a less than iconic work. This is one of many examples of missed opportunities by the MFA. When and if Greenbergian formalism comes back its collection will be viewed differently. It’s most notable for a David Smith “Cubi” which Wayne Anderson was negotiating for City Hall Plaza. It ended up at the MFA.

Right after WWII, when the New York school was emerging, both DeKooning and Clement Greenberg acknowledged Hyman Bloom as a major artist of his generation. That was based mostly on his cadaver paintings. Later, through LSD sessions he did surreal, complex large forest like drawings and spiny fish skeletons. He also painted Ensor-like still life works. There was another aspect to his work, as well as that of Jack Levine, that depicted sentimental Judaica. I was flummoxed by a show of Bloom’s rabbi series. When I asked Jack about it, quoting a scathing anecdote from Hilton Kramer, he said “I came by it honestly.” It’s what I don’t like about the kitsch works of David Aronson. So there is a problematic aspect to Boston Expressionism when compared to the high art of the New York School.

Why has appreciation of Levine been so marginalized?

PH I wasn’t aware that it was.

CG When mustered out of the Army after WWII Jack moved to New York. I visited him there in his studio. Today he is regarded as a political cartoonist.

PH People I hang out with like him a lot. The Midtown Gallery showed the work every so often and now the DC Moore Gallery. He was a fantastic painter if you look at the surfaces. His touch was pretty incredible.

CG A part of this is about the historic anti Semitism of Brahmin Boston and the trustees of the Museum of Fine Arts. The did several history shows from Jonathan Fairbanks on Colonial New England, then “Paul Revere’s Boston,” and Trevor Fairbrother’s “The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930.” There was the Erica Hirshler exhibition “A Studio of her own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940.” Edmund Barry Gaither not long after becoming an adjunct curator organized "African American Artists from New York and Boston." When interviewed Gaither and activist Dana Chandler, Jr. gave different accounts of how that occurred.

There have been niches, like Gaither’s shows, and the Maud Morgan Prize for women artists but no consistent interest and policy for contemporary Boston artists. When asked about that Malcolm Rogers told me that the MFA’s major commitment to Boston art was to the Museum School.

Using the time line for the Fairbrother and Hirshler shows it seems that the MFA lost interest in Boston artists between 1930 and 1940 precisely when there was a paradigm shift from Brahmin to Jewish artists. Bloom and Levine were immigrants as was Karl Zerbe.

The MFA rarely collected Boston’s Jewish artists. There was a Bloom painting “The Christmas Tree” which languished in the basement donated by a Jewish charitable organization. An early Levine came to them through the WPA. Major works by Bloom and Zerbe came to the MFA through the William H. and Saundra B. Lane collection.

Only when the old money dried up was there an effort to embrace Jewish patronage. I wrote a cover story about that for Boston After Dark decades ago.

PH I understand that Erica Hirshler is working on a Hyman Bloom exhibition. It’s a focus show. When she talked with me about it she was very enthusiastic.

CG From my conversations with Bloom’s supporters it is regarded as an underwhelming effort. While it is encouraging that there is interest in Bloom there does not appear to be any for Levine, Zerbe and their followers. There were shows years ago by the ICA under Stephen Prokopoff and in the early years of Paul Master Karnik at the DeCordova Museum. With its greater resources it’s a show that the MFA owes to the Boston art community. The Fogg Art Museum owns a cache of juvenilia drawings by Bloom and Levine given to them by Denman Ross. The Fogg has never shown them as I reminded Ted Stebbins. When David Sutherland was making his Levine film we spent an afternoon looking at the drawings with curator Agnes Mongan. It was the first time Jack had seen them since he was a teenager.

PH Aronson showed in the Whitney Annuals in the 1940s. He’s the one who wouldn’t let BU students see the Alice Neel show.

CG They all showed at Boris Mirski on Newbury Street. I reviewed Aronson’s show of sculpture for Boston After Dark. Alan Fink of Alpha Gallery and Hyman Swetsoff, a major dealer who was murdered, both started with Mirski. After Boris there was no flagship for Boston Expressionism. Individual artists were shown here and there. With The Studio Coalition in 1969 there was a new generation of Boston artists.

On your watch how did you regard the incremental changes at the MFA? With Matthew Teitelbaum as director there is hope for change. Years ago he was a curator at the ICA. Can you comment on changes at the ICA?

PH The ICA generation that I knew was when Elizabeth Sussman was curator. Along with David Joselit and Teitelbaum. They did some damned good shows. They questioned their own history. There was a show on “The Bleeding Heart.” There was a terrific show “Montage and Modern Life: 1919 to 1942” (MIT Press) which Teitelbaum curated in 1992. He and Elizabeth curated “The Bleeding Heart.”

After I was director of the BU Art Gallery for a time I was a columnist for Art New England. I kept up with what was going on in Boston. Trevor Fairbrother was a really good curator but he was pushed out by Malcolm Rogers. There was a very nasty feeling when Rogers fired all those people in 1999.

CG As I recall Malcolm wanted to organize shows highlighting the collection. The irony, of course, that there really was none. Malcolm was behind glitzy populist shows like guitars, Wallace and Gromit, Herb Ritts, and Yousuf Karsh. The America’s cup yachts of William I. Koch were moored in front of the MFA. Will we ever forget the exhibition of Ralph Lauren’s cars? The atrium of the American Wing, designed by Lord Norman Foster, has a Christmas tree like, glass bauble left over from a glitzy Dale Chihuly show. I wonder how they dust it?

PH Trevor had to put on that Karsh exhibition. Malcolm was into marketing.

CG One of the clever ways that Trevor dealt with that was inviting an artist like Brice Marden to pair their work with ones that they selected from the permanent collection. He was behind the Beuys Warhol show and nuanced a Warhol acquisition related to that effort. [Marden is a BU School of Fine Arts graduate.]

PH Trevor was very imaginative. He went to Seattle and got “burn out” there. Now I believe he’s an independent curator.

CG Not long ago he was a guest curator for the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem.

Which Boston artists were you close to?

PH Back in the early 1980s, when Pat Johnston and I were with the BU Art Gallery, we organized a Boston chapter of the Women’s Caucus for Art. Through that I became involved with a lot of women artists. I’m still good friends with many of them. I have great respect for a lot of the artists: Leslie Sills, Prilla Brackett, Bonnie Donahue, Penelope Jencks, Ellen Banks, X. Bonnie Woods, Marianna Pineda. Marianna’s husband the sculptor Harold Tovish was a terrific artist. Carla Munsat, who was editor of Art New England, is making work but I have lost touch with her. Also, Susan Schwalb, the silverpoint artist.

[See Patricia Hills, “Recollections of the Early Years of the Women’s Caucus for Art in Boston,” in Karen Frostig and Kathy A. Halamka, Braze: Discourse on Art, Women and Feminism (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007); available at https://bu.academia.edu/PatriciaHills ]

CG What about Mags Harries?

PH I remember her work for the MBTA. She was casting everyday objects as bronze sculptures.

CG What is your overview of art in Boston; provincial or mainstream?

PH It’s in between. It has a lot to do with the MFA. When I go to cities like San Diego you see work by local artists. In San Francisco they have a huge museum but with large sections devoted to regional and local artists. You see a range of the California artists. Boston needs to do the same thing. They should highlight local artists. Now they are doing a little bit with Hyman Bloom. Dana Chandler is coming into his own because a lot of people are now interested in African American art. There was a big show “Soul of a Nation” at the Brooklyn Museum. It included Chandler.

If they are going to show contemporary art a big chunk of it should be about Boston. If people come here they want to see local artists. They don’t want to see yet another room full of Rothkos. Boston doesn’t have many of those artists anyway.

CG The MFA has a lot of Morris Louis and Jules Olitski.

PH Do they show it? Not much.

CG That’s what Moffett collected. Greenbergian formalism is no longer dominant in the manner it was in the 1970s. In those years when I commuted to Florida to be with my mother, on the way home each year, we focused on visiting different cities along the East Coast. Most major museums seemed to have nearly identical contemporary galleries with formalist abstract paintings and David Smith sculptures. Smith and Ellsworth Kelly have retained status but the others have not. Unfortunately, the MFA doubled down on color field painting during a time of great diversity. It missed the boat on everything else now mostly out of reach. Similarly the collectors were conservative. An exception was Lois Torf who collected prints and works on paper.

PH What about Barbara Lee? You don’t see Larry Poons anymore. Joan Mitchell is an important artist who worked in Paris.

CG I have problems with revisionism. The work has to exist on its own terms. There are so many reversals. Today Frida Kahlo is more celebrated than her husband Diego Rivera. During their lifetime the opposite was true. Kahlo is indeed a major artist and the MFA recently acquired one of her works and created a small exhibition to support it.

PH There is a change for how women and black artists are viewed today.

CG It’s certainly true in the academic world. When I neared retirement there was a shift. Truth is, today, I would have a more difficult job getting hired. There are good and bad aspects of this. It’s not democratic.

PH Democracy? What’s that? There are things we haven’t talked about. Like my fight against the deconstructionists in the 1980s. I made fun of them and got in trouble for that. At Yale there was a stronghold of deconstructionism on the teaching and theory of American art. Also Brian Wolfe, David Lubin, although he changed his mind. They were influenced by deconstruction and the idea that all interpretations are equally valid. Paul de Man taught English at Yale. They followed Jacques Derrida (Algerian French).

My students were interested in these ideas. I told them that the notion that all interpretations are equally valid is absolutely not true. There are some interpretations that are way off base. While some, in the context of the times, make sense. Deconstructionists tend to insist that all are equally valid.

It’s a big subject and I don’t want to get into it. Paul de Man had written anti-Semitic, pro Nazi articles in the late 1930s. It is not surprising that his philosophy was that we can never know the truth.

These guys at Yale started looking at everything and seeing penises and breasts. There is the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan who rejects Freud. To me it’s all about male fantasies.

It’s a long story but these academics were shocked that I was going against what I called The Yale Males. They made women feel totally out of it.

They would look at a Thomas Cole painting with mountains and they would see breasts. Or Eakins “The Dr. Gross Clinic”: the hand holding a scalpel they would see as a penis with blood on it. Where are you going to go with those kind of interpretations? It was all fantasy land.

I made fun of these people. Once I organized a panel at a meeting of College Art Association in the mid eighties: “The Uses and Abuses of Deconstruction in Art History.” I said that with these male academics it was like a circle jerk, and that got a lot of laughter.

At one point Michael Fried muttered “I’m not going to allow myself to be attacked by these low grade terrorists.” That’s what I was accused of being.

CG Are you a reactionary Marxist?

PH I’m a Marxist progressive. There’s not enough grappling with capitalism. We’re going to have shitty everything until capitalism is gone. Capitalism depends upon the exploitation of people. You can’t get away from it. They’ve got to make their profits. If someone is making profits then someone is not getting their fair share of the deal.

CG Have you been to Crystal Bridges? [In Bentonville, Arkansas the home town of Walmart.]

PH I would like to go there. Although I don’t like Walmart, I would like to see the collection. Alice Walton has been trying to buy all the great American masterpieces. But Arkansas needs a good museum.

CG Astrid and I went to Bentonville feeling prejudiced and came away converted. They have so many iconic paintings that you find illustrated in text books. It is such a shock and surprise to find them there. Scholars have to deal with that.

But we were totally impressed with their programming and outreach. Busses bring students from all over the region. There is funding for transportation, docents and lunch. That’s a great experience for kids with few opportunities to visit major museums. It serves a large and culturally deprived region of rural America.

The design by Moshe Safdie is a series of pods/galleries sited over a stream dammed to create a pond. The museum appears to float on water and is surrounded by nature. The architecture is a significant part of the experience. They have also expanded programming and collecting into 20th and 21st century art. If possible we would like to return.

The former director of Crystal Bridges, Don Bacigalupi, organized a biennial scaled exhibition of regional artists from all over America. It was widely covered. He is now the founding director of the George Lucas Museum of Narrative Art which is being developed in Los Angeles. They acquired “Skeffington’s Barber Shop” by Norman Rockwell in a controversial sale by the Pittsfield Museum.

PH Robert Workman, who had an MA from BU and was my student, was Walton’s curator and actually the founding director.

I think that Asher B. Durand’s “Kindred Spirits” should have stayed in New York [NY Public Library]. It is so much a New York picture. I’m glad that “The Dr. Gross Clinic” by Thomas Eakins remained in Philadelphia. The city raised a lot of money to keep the painting.

I have corresponded with Crystal Bridges. They have a collection of my books. I sent them things so that they would have all of my books. They were very happy to get them.

CG In addition to Alice Neel you did a book on Jacob Lawrence. What are the others?

PH I’m very proud of my scholarship on Jacob Lawrence. I met him back in the 1970s when Milton Brown did the Lawrence exhibition for the Whitney. I took slides of that show and showed them to my students at York College, where I taught from 1974 to 1978. When I did my exhibition Social Concern and Urban Realism: American Painting of the 1930s, I did interviews with him. I was fascinated with his style – an expressionist and figurative cubist style – and with his singleminded focus on topics that addressed the struggles of black people. And he was such a thoughtful, intelligent man, with a still beautiful wife, Gwendolyn Knight. So I started writing essays on his series paintings: The Harriet Tubman series and the Migration Series.

I had a fellowship at the Du Bois Institute, Harvard University, the year that Skip Gates (Henry Louis Gates, Jr.) came to teach and direct the Institute. We became friends and he was a big influence on me. Skip gave me—a white female—the confidence to write about a black male. He doesn’t care who writes on African Americans, just as long as it is good scholarship. So I’m a big fan of his. I got an NEH in 1995 to research Lawrence’s work further, and then four fellowships in 2005-06 to finish the writing. The book, Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence (2010) has just been reprinted by the University of California Press. I’ve written on other black artists, such as John Wilson, Whitfield Lovell, Romare Bearden.

I’ve done a ton of catalogues. I did books on Alice Neel, Stuart Davis, May Stevens and now I’m working on a book on Joyce Kozloff. She is very opinionated. There’s renewed interest in pattern and decoration. My book on Modern Art in the USA is being translated into Chinese.

CG You did memorable shows for the Whitney Museum.

PH I co-curated a show called “The Figurative Tradition and the Whitney Museum of American Art” with Roberta K. Tarbell. That was in 1980 and was based on works in the museum’s collection. Earlier we were talking about realism. For that show I brought out of the basement works by Philp Evergood and others not seen in decades. The show’s works ranged from the beginning of the 20th century to Philip Guston and Audrey Flack.

CG Was your last Whitney project the John Singer Sargent show?

PH That’s right—1986. It went to The Art Institute of Chicago. That was the exhibition which Ted Stebbins sabotaged. I had to postpone that show for three years because he pulled the rug out from under me. I had gone to talk to him and he knew I was doing the Sargent show. It was a snobby thing. He and some colleagues thought that Pat Hills shouldn’t be the one to do a Sargent show. You know, I’m a woman and too lefty. All of that. He acted as though he was very cooperative and would lend works from the MFA. Then, behind my back, he did that big show which went to Paris. He got the major Sargent paintings. People told me, Pat, we couldn’t turn him down. He even wrote me a letter saying “Sorry. I had to ask for these paintings for my show so you couldn’t have them for your show.” It was a show of masterpieces. There were no African American artists. People protested in Boston, so he included a (Henry Ossawa) Tanner. I had to postpone my Sargent show from 1983 to 1986.

[A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760-1910. Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Carol Troyen, Trevor J. Fairbrother, 1983, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C, Grand Palais, Paris. From 7 September, 1983 to 11 June, 1984. The exhibition included “Madam X” (Madame Pierre Gautreau) 1884, “Dr. Pozzi at Home” 1881 and “Venetian Interior” 1882, by John Singer Sargent. It is notable that the provenance of several of the “masterpieces” has changed including works acquired by Crystal Bridges.]

CG Speaking of Tanner: his masterpiece “The Banjo Player” is owned by Bill Cosby who has an important African American collection. At BU you showed the collection of George and Joyce Wein. He was a BU grad who went on to found the Newport Jazz Festival (with the Lorrilards). Speaking with him he sold a lot of that work because he had money troubles with the festivals (jazz and folk).

PH Wein sold the festivals and then decided to buy them back. He acknowledged to me that because of our show he was able to get really good prices for the works. At some point he gave $1million to set up a chair in BU’s African American Studies program. They always hoped that he would give them more money.

CG Why doesn’t Boston University have a museum and what’s happening with their archive?

PH Regarding a museum it’s a matter of money. Somebody has to endow it. They don’t have a collection. There are a few artworks there. They are under the control of the archives. The retired head archivist Howard Gotlieb was very entrepreneurial, loved celebrities, and got the Bette Davis archive. I talked with him once about the Sargent archives going there, and he was enthusiastic about that. When he retired they put in his long-term secretary. Vita Paladino rose through the ranks and became head archivist. [Retired as of June 31, 2019.]

CG I recall after the war when BU had a number of temp buildings—a series of quonset huts where the Marsh Chapel and student center are located. My uncle and many vets attended through the GI Bill. The status of BU was on a par with Northeastern University. They were regarded as commuter schools. How has that changed and how is BU regarded today?

PH BU is on the forefront in many fields. As of last year they had risen to 43 in the list of universities to go to. There are some very good departments. My granddaughter is applying to BU because they have a very good theatre program. She lives in San Diego and is applying to BU. The fine arts program is much improved. All they used to paint were stilllifes of Chinese takeout cartons. That’s changed. The science programs are very good. Now BU is very hard to get into. It used to be a backup school but now they admit one in ten applicants.

One thing you can say about John Silber (1926-2012) is that he knew everyone on the faculty. The new president, Robert A. Brown who was the provost at MIT, doesn’t know anybody.

CG What was your relationship to Silber?

PH He saved me. I had a rough time going through tenure. There was a split vote. The people voting against me were Fred Licht, Naomi Miller, Alice Binion, and Hellmut Wohl. Voting for me were Carl Chiarenza, Mel Wiseman, Fred Kleiner, and maybe John Kirk. I was running the art gallery and he (Silber) called me and said “I can’t overturn a negative vote in your department.” He said that in the University APT it was a unanimous positive vote. I was called “a jewel of the university.” He said “Would you go on a five year contract as the director of the BU Art Gallery?” I asked if I was still teaching, and if so, could I get reduced time for running the gallery. He told me “Reduced time is an invention of the 1960s.” I said “OK,” so I had two jobs. I had five years to find a new job instead of one year. I took the deal, and eventually I did get tenure.

The year I got a Guggenheim fellowship, I was the only person at BU to get one. You know the people in my department, half of them wouldn’t speak to me. They were so outraged that I had gotten a Guggenheim. That was the avenue whereby the upper administration reversed the (negative tenure) decision.

CG Regarding the department opposition was that against you as a leftist or a prejudice against the field of American art? How do you sort this? Was it personal or professional?

PH It was a prejudice against me because I was a woman, married, and I had a baby and family. There were women in the department who had given up the idea of having children, or maybe they never wanted children. They didn’t like me. They didn’t like that I was doing American art because that’s so “easy.” It’s not a real art history subject. It was also that I was young and energetic. I would get a bus and take my students to New York to visit museums. Nobody had done stuff like that. I was out pacing them. I was out publishing them. I had a family and I was a Marxist. Someone said “You don’t smell right.” I wasn’t one of them. I wasn’t in their tribe.

CG Did you know Howard Zinn?

PH I didn’t know him well. I respected him and he respected me.

CG On your watch to what extent was BU a radical campus?

PH It was never a radical campus, but there were strong radicals on the faculty.

CG What about Ray Mungo, the BU News, and Liberation News Service? Many BU graduates were my colleagues in the counter culture and Boston media.

PH They were beaten down by Silber. The Faculty Council became radical and anti Silber. They fought him tooth and nail. He tried to fire a lot of those people but wasn’t able to.