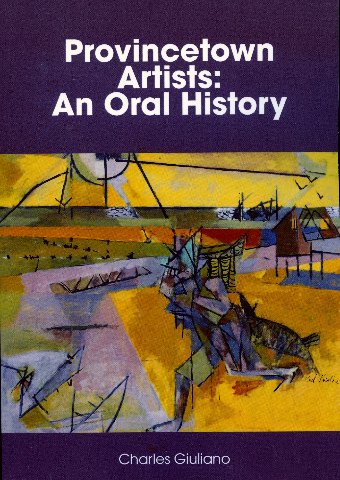

Provincetown Artists: An Oral History

Spectacular Nature Inspired Generations of Leading Artists

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 25, 2025

Provincetown Artists: An Oral History

394 pages, illustrated

Published by Berkshire Fine Arts, 2025

ISBN 978 -0-9961715-9-5

Available at Amazon, $30.00

In addition to numerous exhibition catalogues, since 2014, Provincetown Artists: An Oral History is the ninth book published by Berkshire Fine Arts. Research started in the 1980s and was completed with interviews and archival search in October, 2024. Jim Zimmerman of Provincetown Art Association and Museum was invaluable in providing many of the images in the profusely illustrated book. In the months that followed yet again I worked with editor Leanne Jewett and the design team of Studio Two. Astrid Hiemer has been an inspiration involved in all aspects of this series of books.

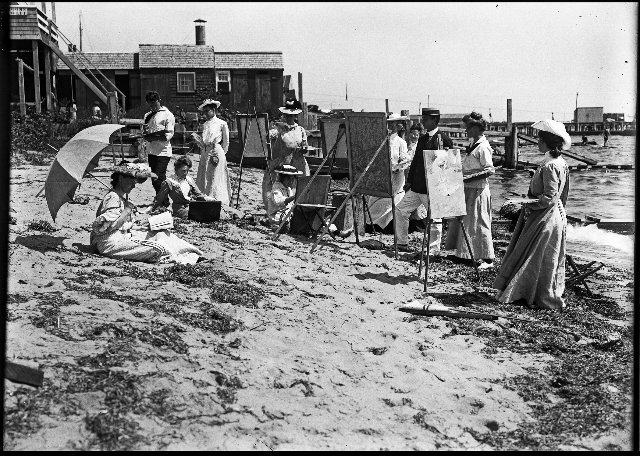

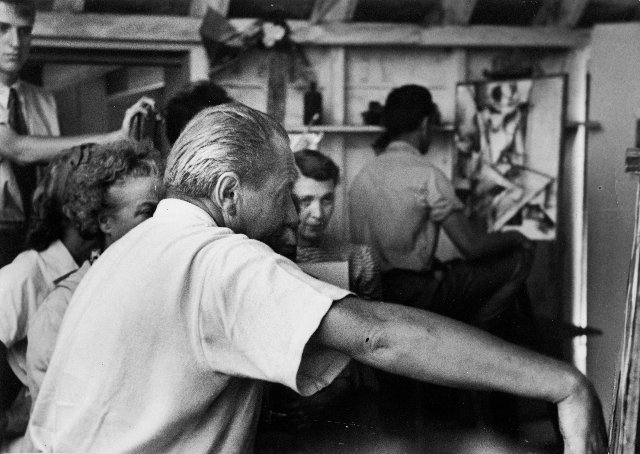

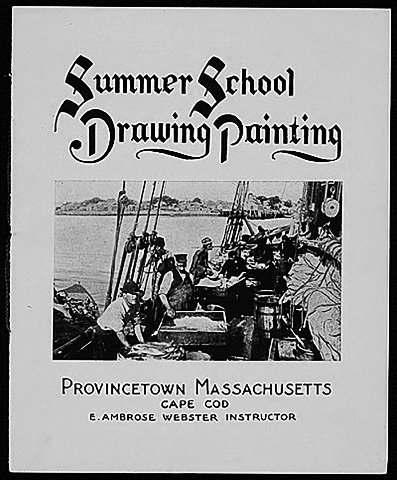

In 1899, Charles Hawthorne established the Cape Cod School of Art. E. Ambrose Webster continued the teaching of plein air painting as did Henry Hensche a generation later. In the 1930s the German artist, Hans Hofmann, taught abstraction derived from the study of nature. After the war, students flocked to study in

During WWI artists returned from Europe and settled in

Women were prominent among the repatriated artists. One couple, Maude Hunt Squire and Ethel Mars, were mentioned in the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein. The sisters Helen and Agnes Weinrich initially rented in

The Weinrichs became involved with the young, Midwestern artist of German heritage, Karl Knaths. It is speculated that he loved Agnes but when she was unavailable married Helen. From recycled material he built a house with studio and several smaller studio structures. They earned rental income and Tennessee Williams was a tenant. The three lived together until Agnes died at 72 in 1946.

The Provincetown Art Association was established in 1914 with its first juried exhibitions in Town Hall. The organization later bought and renovated adjoining properties. Under current director, Christine McCarthy, Provincetown Art Association and Museum has been expanded and renovated with an emphasis on growing its collection and archive.

Early on, Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt (1878 –1955) invented white line prints. It was a technique of hand inking a wood block to create a multi colored image. Many artists worked in this manner and it is a signifier of

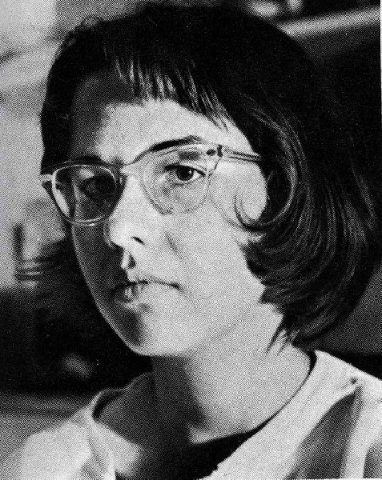

During the 1980s, while a graduate student at

Dr. Nathaniel Halper was a Joyce scholar, collector and gallerist. He was director of the renowned HCE gallery. When it closed he continued as a collector and private dealer. My interview with him was richly detailed and provided a base for further research. He passed at 75 in 1983 a year after we met.

Nat introduced me to his business partner, Mervin Jules. Resulting from childhood illness he got around on crutches and an early, small, electric car. A social realist artist during the WPA he was then board president of PAAM. He and Nat showed me their inventory of

Initially, I sought out individuals and artists connect to Knaths. I met with banker Ken Demaris who liquidated the estate and private dealer Ed Shein who bought 100 paintings and numerous works on paper from the bank. The elderly Ferol Sibley Warthern studied with Knaths and explained his complex color charts and compositions. During winters Knaths was part of a study group translating important German art writing that was not then available in English. Joan Wye and Jim Forsberg discussed this activity. Their information was essential but redundant and I opted not to include their interviews.

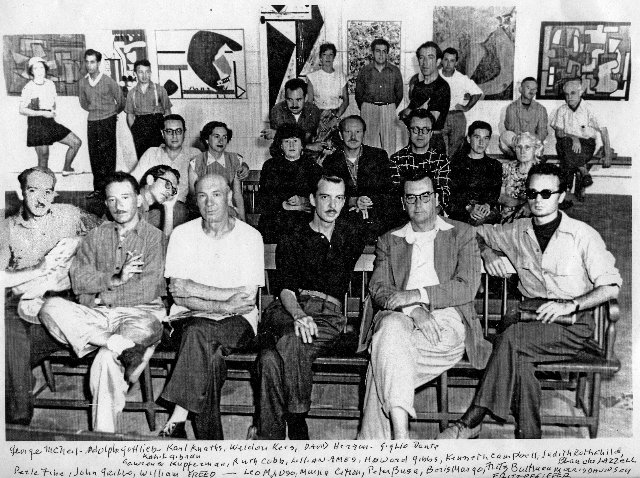

Meeting the artist, collector and philanthropist Judith Rothschild proved to be a tipping point. She studied with Knaths and with her former husband, author Anton Myrer, were involved with the study group. Like Warthern she explained the Knaths system which for a time she emulated. She was a founding member of the cooperative Long Point Gallery. Also, she put me on track for the seminal event Forum ’49 which was essential to the theoretical development of Abstract Expressionism and the

It was the inspiration of poet/ artist/ jazz musician, Weldon Kees. Exhibitions, lectures, panel discussions and events were staged that summer in a popup gallery in a converted garage. The conservative PAAM had nothing to do with the program. Jackson Pollock participated in what is speculated as the first group exhibition of the Post War avant-garde.

Significantly, Knaths who participated in Forum ’49 as a juror and panelist, was a prize winner in that controversial Met exhibition. He was on the wrong side of a seismic shift in American art. Interest in his work gradually declined. During visits to

Harry Weldon Kees (February 24, 1914 – disappeared July 18, 1955) was one of the Met protesters but missed the photo shoot that famously was published by Life Magazine. His car was found abandoned next to the

Long Point Gallery was founded when Leo Manso did not want to give up its generous space. In 1977, he closed the art school that he and Victor Candell had run for 18 years. I interviewed Manso, Rothschild, Nora Speyer and Sideo Frombolutti, as well as Tony Vevers. Fritz Bultman and Hofmann’s wife took the last boat from Nazi Germany. Bultman was undergoing chemo therapy when we met.

No account of

There were many historic galleries in

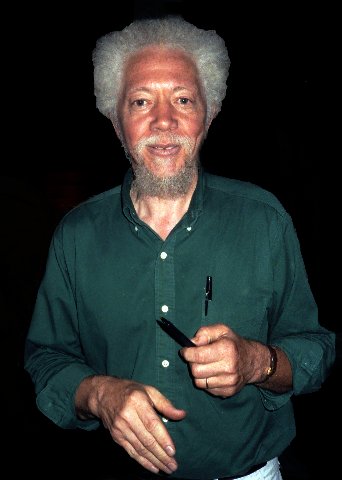

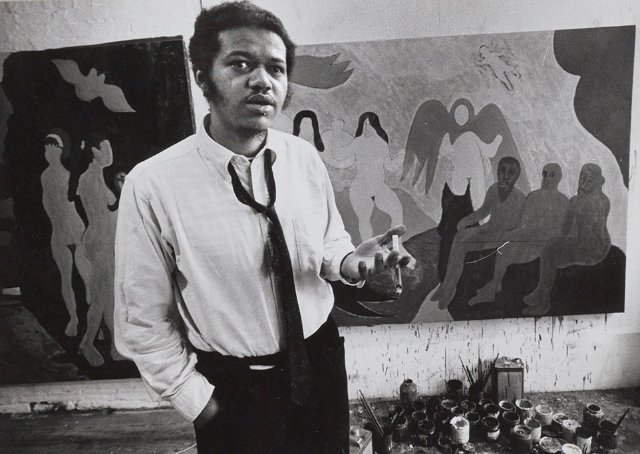

Bob Thompson and Lester Johnson were represented by

Hecker was invaluable in assisting me to borrow major works by Thompson and his friend Emilio Cruz. Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emelio Cruz, Earle Montrose Pilgrim and Benny Andrews was ground breaking by featuring four African American artists who worked in

While now obscure, Myron Stout was a leading abstract artist of his generation. It took years to complete a work and he rarely exhibited. Stout had a retrospective at the

From a focus on Knaths visits and research broadened. I became a friend and colleague of Chris Busa of Provincetown Arts Magazine. He published my Kind of Blue essay at a time when PAAM had limited resources for catalogs. We shared laments of years languishing as graduate students; he at

The book features then and now profiles of directors of PAAM. Ellen O’Donnell/ Rankin provided a vivid view of a “Golden Age” for the arts. Running a rich program with limited resources was enormously challenging. It’s a time when P’Town was fun and affordable. Christine McCarthy has brilliantly navigated through the present when every quaint shack and modest dwelling has been yuppified. That has upended the social dynamic of the community. This has been particularly detrimental to artists. There are programs like Fine Arts Work Center that lures young artists and writers. Few remain after their fellowships. She spoke with me of taking over a museum with a leaking roof and inadequate storage for a growing and ever more valuable permanent collection.

Jay Critchley grew up in a large Roman Catholic Family. He and his sisters performed on TV as contestants for the Ted Mack Amateur Hour. They won their first appearance but were voted off the following week. When he visited with wife and young son there was an intuition that something wasn’t right. He told me that first he had to come out as gay and later to come out as an artist. Each process was equally traumatic.

He worked with the non profit Drop-In-Center which struggled to provide free health care. Dr. Doug Kibler was a colleague and lover. They bought a ramshackle property with a large back yard. They split up and when Kibler died Critchley managed to buy the property from the estate. “Thank God,” he told me “How else would I afford to live here.” Jay developed as an inventive, somewhat gonzo conceptual artist. His annual Swim for Life has raised millions for charity.

The maternal grandparents of Berta Walker came to