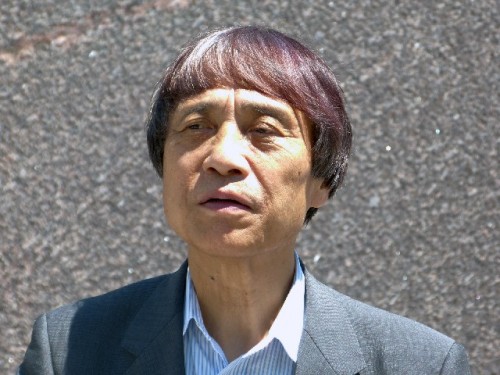

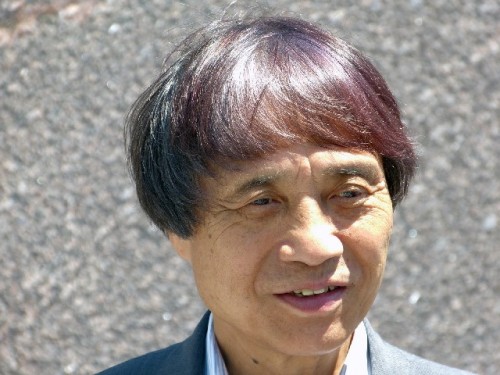

Japanese Architect Tadao Ando: A Portrait

Pritzker Prize Winner Designed Clark Art Institute Expansion

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 28, 2014

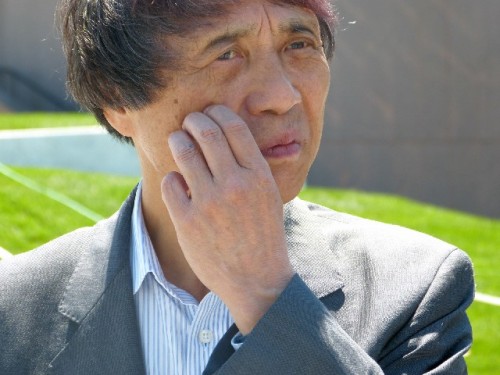

On a scorching hot, clear, bright Berkshire afternoon the architect of the Clark Art Institute’s expansion, Tadao Ando, who speaks no English, mostly kept apart during a well attended gathering of the media.

Through an interpreter he took some questions. I asked about the use of water in his work. The terrain of the Clark campus connecting several disparate buildings is unified by a vast, shallow, three tiered reflecting pool.

It was a solution to managing a complex site with wetlands, underground streams and runoff into streams and ponds.

The resultant use of water, as is typical in his work with sensitivity to nature and the elements, is both pragmatic and aesthetic.

It took time to convey the question and then a pause for the answer.

We were near the edge of a glass surrounded space at ground level in the multi purpose visitor’s center and special exhibition area. Two thirds of the building is below.

He responded that even though induced and artificial in this instance the element of water is important to his work by reflecting its surroundings. He pointed above to the soffit at the edge of the roof which was catching the flickering, dancing reflections of the pool.

Descending to the lower level and sitting in the lounge/ dining area we looked out at a narrow expanse of water. There was also a striking sense of a light and transparency which, with the elements of cast concrete balanced with granite walls, are signifiers of his approach with a deceptive, modernist simplicity understating pragmatic functions.

In an approach that reflects Ando's Japanese heritage he has stated that the architecture he designed should not attract attention to itself. It is deceptively calm on the exterior containing and surrounding complexity within.

As the Clark’s director, Michael Conforti stated during opening remarks the true element of a museum is not its architecture but the programming within. In this regard Ando has provided exquisite and versatile, multi purpose space.

Conforti stated that Ando was the unanimous choice of the search committee. Primarily because he offered the best solution to cleaning up the mess of outmoded and awkward building and the mechanics that they entail.

In Ando’s design there are important functions of the museum, such as a loading dock and underground connection between buildings to circulate works of art, HVAC, and other aspects that he has concealed from view.

Western writers who describe his work evoke analogies to Zen Buddhism although the architect has described himself as an atheist. One of many enigmas he is known for creating contemplative religious structures, These include the Church on the Water in Hokkaido (1985-88), the Church of the Light in Osaka (1987-88) and the Water Temple in Hyogo (1989-90). "I do not believe architecture should speak too much," Mr. Ando has said. "It should remain silent and let nature in the guise of sunlight and wind speak."

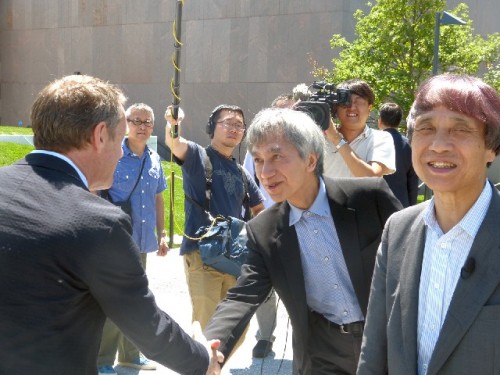

During this media day Ando was wired and followed about by a Japanese film crew. He seemed to be examining his own creation now in completed form. In his hand was a point and shoot camera. Now and then he paused to take a photo as did others in his entourage.

When encountering an array of American collaborators and the museum’s administrators there were formal bows. There were occasional smiles but for the most part the body language of the architect did little to reveal the character and personality of the man.

Ando was born in 1941 in Minato-ku, Osaka, Japan, and was raised in Asahi-ku in the city. He worked as a truck driver and boxer before settling on the profession of architecture, despite never having taken formal training in the field.

When in 1995 he won the Pritzker Prize, the most prestigious in the field of architecture, most of his work was in Japan. He was the third and youngest Japanese architect to win the prize since it was initiated in 1979.

As a school boy he was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo which was later razed. He traced the designs by Le Corbusier in a book he purchased. He trained himself by reading and traveling extensively through Africa, Europe, and the United States. In 1970 he established Tadao Ando Architect & Associates. This ended his career as a professional boxer.

In its minimalist, horizontal line accenting the 150 acre bucolic campus of the Clark, the design by Ando evokes the international style, Bauhaus, form follows function, less is more paradigms of classic modernism.

But there is a uniquely Japanese aspect that reveals itself surreptitiously. The architect conceals nature between the seven shaped walls that greet one approaching the visitor’s center and then the Stone Hill pavilion that looks down from an edge of the campus.

Having concealed or walled off nature it is then revealed to us as we enter the space. There Ando gives us back our view but under controlled and bracketed circumstances. He has harnessed and constrained our point of view and encounter with natural surroundings.

It evokes the sparing simplicity of a Japanese interior where the display of flowers, a branch of cherry blossoms or a single chrysanthemum, accompanied by an ever changing kakemono marks the changing seasons. The term haiku is commonly associated with his architecture.

The new Clark, with its reflections on nature, invites us to return for many different experiences and seasons. Through Ando it has become a locus for peace, serenity, a magnificent collection and changing exhibitions of one of America’s finest museums. Which is now spectacularly better.