Americans in Paris 1970s

Dishwasher Dialogues

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Jun 29, 2025

The American Center in Paris

Greg: Chez Haynes had a counterpoint, of sorts, in the American Center in Paris. Not only by virtue of it hosting jazz concerts in its heyday a decade earlier, but also because of its focus on experimental theatre, dance, and poetry and its welcoming of young writers and performers. The Center was down on my side of Paris, 261 Boulevard Raspail, not far from the Tour Montparnasse; back then a brand-new monolithic beast (which ended up saving Paris from further skyscraper assault).

Rafael: The American Center in Paris, yes.

Greg: Like Chez Haynes, the Center was in a partial state of decay. It was a beautiful, peeling white, collegiate looking structure that had aged impeccably, which is to say perfect for young artists looking to try out rough and ready, flawed, and blemished ideas. It was friendly and convivial and not the least bit intimidating. There was nothing institutionalized or ‘high art’ about it. (Very unlike what it became a few years later under its Frank Gehry incarnation in Bercy.) For a few years, it became a local home. Although I have no idea how I stumbled onto the Center—I think through you.

Rafael: My brother Alex had been named administrative director of the place and he helped us. It was a big “in” for us, I don’t deny it. Hell, we needed some breaks, just like everybody else, n’est-ce pas mon ami?

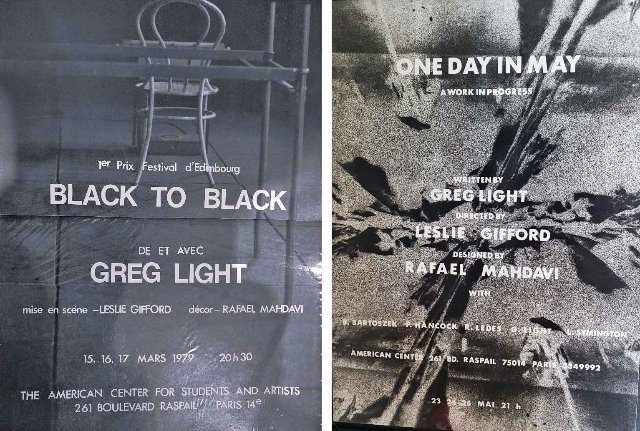

Greg: That sounds right. So, we did have a connection. A good one. And, by then, a bit of an artistic record, plus ideas and energy. We staged both plays—Black to Black and later One Day in May—in the theatre there. They were also committed to providing a range of arts courses, alongside their language courses. And I was happy to oblige, with my experimental theatre course and Paris metro field trips. There was not a lot of money in it, but I remember having about a dozen students, mainly between twenty and forty-five years of age and all French. My French was never brilliant, but I was quickly able to master the vocabulary and rhythm and intonation of the doings in this context—an experimental theatre class. When I was in class, I almost felt fluent. Of course, we were doing experiments with the use of language, so it was a natural fit where we were all equally way out of our depth. Nevertheless, the students stuck with me.

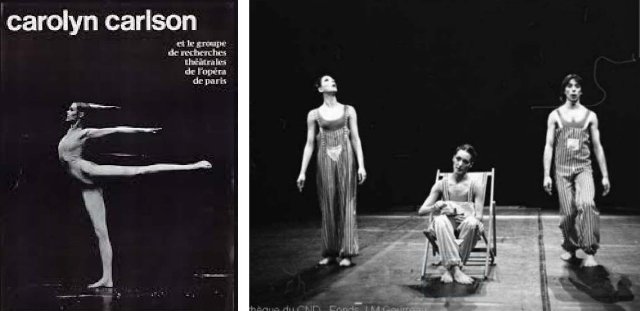

Greg: That was also during my contemporary dance phase. I felt I needed some movement training for my performances. Maybe after seeing Carlson at the Opera? For a while I was into dance, particularly the visual freedom it permitted. At one point I attended a few of Carlson’s improvisation workshops at the Opera. I have very little memory of it; other than it connected me to a young French dance troupe – Le Four Solaire - up near where you later lived in the 11ème. I took a dance course with them and fell deeply in love with one of the instructors. The kind of ephemeral love one can only have for a dancer. I couldn’t keep my eyes off her, especially when she danced. Unfortunately, my own gauche dance technique did not reciprocally inspire.

Rafael: Don’t be so hard on yourself and your memories and your body. There could have been a lot of reasons it didn’t work out. The stars weren’t lined up, or she was a lesbian, or married or a guy in drag. So maybe you were lucky.

Greg: It was the kind of love in the moment that fades quickly after the film credits ebb, and the performance comes to a close. Or the dance course ends. Which it did. But it did not curtail my interest in dance. Molly (Leslie), who directed me in Black to Black, started teaching a contemporary dance class at the American Center and asked me to join her. I even taught it a couple of times which was insane. I had no profound background in dance. But by then I had learned the basic moves and exercises and could put a few steps together into an activity. And it doesn’t take too many activities before you have an actual piece. You will remember that the performed version of One Day in May was heavily influenced by dance and not just because we were all in dance leotards painted the same colors and designs as the rags that you had created.

Rafael: At first, for the stage set, I wanted the actors cum dancers to come on stage naked and proceed to dress with the rags which made up the stage design. I suggested we hide the underwear and bras in the rags. The whole idea was nixed. So much for sexual freedom, eh?

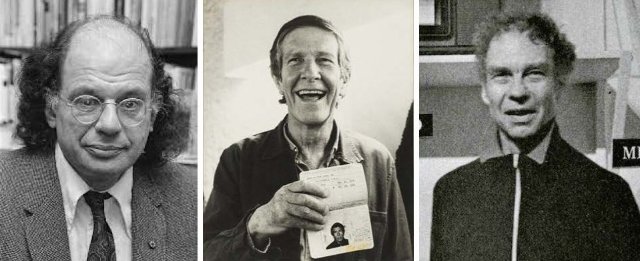

Greg: I think we gave the actors the freedom to vote. Sometime during our time at the center, Henry Pillsbury took over as the artistic director of the Center. He and Judith Pisar (who I think was chair of the board) were very strong on inviting some of the most well-known American avant-garde artists, musicians, and writers to perform and conduct workshops at the Center. I especially remember encountering Merce Cunningham, John Cage and Allen Ginsberg at one point of another. I have a vivid recollection of watching John Cage setting up and rehearsing an enhanced performance of snails and/or slugs crawling on branches and leaves or something to that effect. He had placed very tiny and delicate microphones in their aquarium which he had wired up to a then state-of-the-art sound system so that he could play the sounds they made as they chewed or moved around, and then would curate or ‘disc jockey’ their different noises into a sound performance.

Rafael: My brother played chess with John Cage and wasn’t polite enough to let him win. Cage was not a very good chess player, but he admired Marcel Duchamp who liked chess.

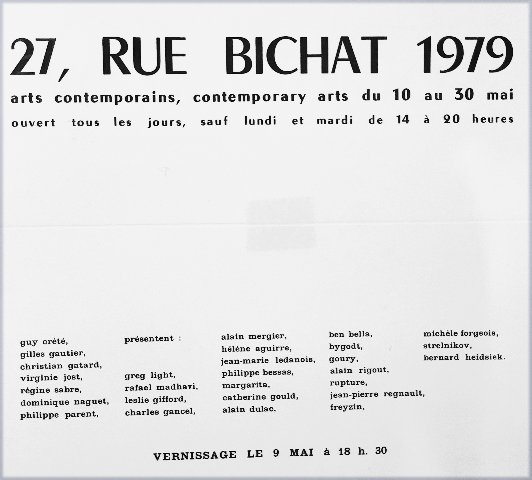

Greg: I am sure there could have been a sound composition in the chess moves to rival the journey of the snail. Not that I was immune to the charms of Cage’s methods. When Allen Ginsberg visited the Center— around the same time as Cage and Cunningham—he headlined a day long international poetry festival. Dozens of French poets and many from sundry other countries were invited to give readings. I remember being invited (or I inveigled my way into the line-up.) We were permitted one poem each. I performed One, Two, Three, Point. It was a short poem (six stanzas) about a ‘sentence’ and I read it out five times. Each time I read it, I did so with a different vowel sound: Ain, Tay, Thray, Paint; Een, Tee, Three, Peent; Own, Toe, Throw, Point etc. It sounded even more bizarre than it looks on paper, but it went over very well. I wasn’t carried off in triumph, but the response was more enthusiastic than polite applause. Which was, in any case, in keeping with the tone of the event. It was a festive day with a crowded and enthusiastic audience. Soon after that reading, we ‘exhibited’ this poem in a shop front art gallery in the 10th arrondissement. I have a note that it was called Galerie Bichat.

Rafael: It was a gallery space on Rue Bichat. 27 Rue Bichat.

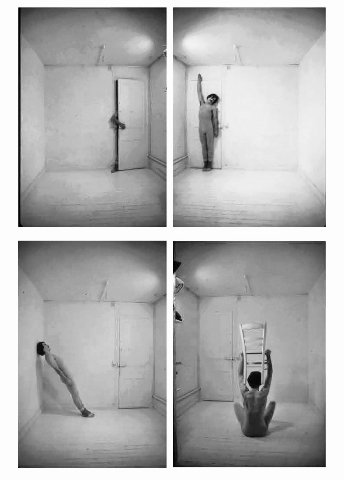

Greg: I recall it having multiple spaces. There were other artists exhibiting as well. Mainly French, I think. We were given a completely empty space/room which we painted entirely white. We audiotaped the poem on a repeating, rolling tape recording. You took a dozen photographs of me in different poses in my dance leotards, developed them, framed them, and hung them in a straight line at eye level on the three walls of the room. All the while, the tape recorder sat on the floor in the middle of the room repeating the same poem over and over.

Rafael: I remember this clearly. It was a wonderful dance slash performance. Again, here lack of money played a role. We didn’t have video easily available then. We must have filmed it. I have never seen what we filmed, nor have I come across the photos I took. Maybe somewhere I have the negatives in a brown envelope. At moments I imagine our Paris years stuffed in a brown envelope, in a suitcase, in an attic somewhere. Good title, ten years in a brown envelope.

NEXT WEEK: PARIS, WITTGENSTEIN and LOVE