Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes at National Gallery

When Art Danced with Music Through September 2

By: Richard Friswell - Jul 02, 2013

The Ballets Russes—the most innovative dance company of the early 20th century—propelled the performing arts to new heights through groundbreaking collaborations between artists, composers, choreographers, dancers, and fashion designers. Founded by Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev (1872–1929) in Paris in 1909, the company combined Russian and Western traditions with a healthy dose of modernism, thrilling and shocking audiences with its powerful fusion of choreography, music, and design.

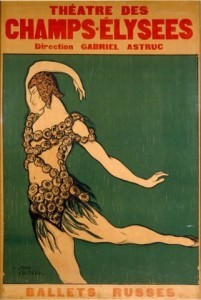

The current show at the National Gallery, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909–1929: When Art danced with Music, showcases these collaborations with more than 130 original costumes, set designs, paintings, sculptures, prints and drawings, photographs, and posters, focused around specific historical performances, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes also incorporates film clips, meticulously recreated by later dance companies in a series of theatrical multimedia installations. Adapted from the exhibition conceived by and first shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in 2010, the presentation in Washington surveys some 80 works from the V&A’s deep collection of dance artifacts, with 50-or-more additional objects, offered from private and public collections. fine arts magazine

Diaghilev’s success depended primarily on his ability to identify and bring together the most creative artists of his day. Recognizing the vitality of contemporary art, he called upon the famous and the aspiring in every creative realm, to create dynamic set designs and exquisitely decorated costumes that shared a unified aesthetic. They, in turn, brought the most important artistic developments of the early 20th century—including futurism, cubism, and surrealism—to the ballet stage.

Diaghilev also commissioned ballet scores from innovative composers noted for their technical brio, making the company a breeding ground for musical and choreographic innovation. Together with the most important dancers of the day, he encouraged experimentation to dramatically expanded the vocabulary of movement. The troupe’s productions, notably the infamous Rite of Spring—now celebrating its 100th anniversary—instigated loud protestation among the opening night audience and led, not surprisingly, to a revolution in dance.

The list of creative notables who were attracted to Diagilev’s vision for revolutionizing the performing arts reads like a preferred guest list of manywho would define modernism at the turn of the century. While this exhibition features these and other connections fostered by Diaghilev, many noteworthy highlights of the show deal with the costume drawings and set designs of such early 20th century. Their collective vision for the modern stage are all gathered here at the National Gallery. Luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Coco Chanel, Sonia and Robert Delauney, Georges Roualt, Jean Cocteau and Surrealist Giorgio de Chirico, among others. Composers, too, like Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, Serge Prokoviev and Darius Milhaud wrote for the new audience; and the like of Vaslav Najinsky, Léonide Massine and George Balanchine danced with Diagilev’s cast. The ties, affiliations and personal connection ran deep, and for twenty years, until Diagilev’s death in 1929, the pioneering efforts of the company drew from both Russian and Western traditions to shock and amaze its audiences.

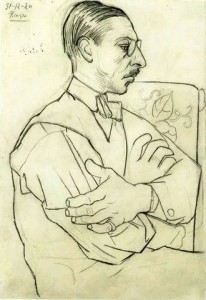

Little-known, but brilliant costume and set designer, Léon Bakst—master of color and dynamic imagery—is the face of the exhibit itself, with his sketch for Diagilev’s appearance in Afternoon of the Faun appear on all show promotional material. Branding the exhibit with a Bakst image recognizes his unmistakable skill as a draftsman and the animation imbued in every drawing. Consider him the James Audubon of costume design, as his ‘feathered birds’ do more than merely assume the static posture of the artist’s model. As if auditioning for the part, his figures prance, preen, sulk or pose languorously for their imagined audience, as he breathes life into characters long before needle passes through thread or dancers step on stage. His dramatic Art Nouveau styling takes the painfully formal images of this Edwardian period and puts them on steroids—fin de siècle meets Madi Gras!

Born in Russia in 1866, Léon Bakst belonged to a new generation of European artists who rebelled against 19th century stage realism, which had become pedantic and literal, without imagination or theatricality. There were no specialist trained theatre designers, so painters like Vuillard in France, Munch in Scandinavia and Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois in Russia turned their painting skills to theatre design.

Bakst came into the theatre on the wave of choreographer Michel Fokine’s revolution in Russian ballet. Fokine rejected full-evening ‘story’ ballets, like Swan Lake, where the romantic storyline was told in formal mime, interspersed with virtuoso dances. Ballerinas would wear pink satin pointe shoes and tutus decorated with appropriate symbols—lotus for Egypt, key pattern for Greece, vines and leopard skin for bacchantes), whatever the subject or setting.

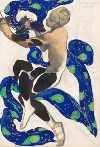

In Fokine’s ‘new’ ballets, the theme dictated the style of the choreography, music and design; the steps were imbued with meaning and emotion. As part of the creative team, Bakst produced designs suited to each particular ballet—Orientalism in Scheherazade and Cleopatra, Ancient Greece in Daphnis and Chloë and Narcisse, Biedermeier in Carnaval and Spectre de la Rose, and 18th century style in The Good-Humoured Ladies and The Sleeping Princess.

This ‘new ballet’ became the rage of Paris in 1909, when audiences went wild for the color, exoticism and barbarism, especially in the ballets designed by Bakst. As Bakst put it:

“It is goodbye to scenery designed by a painter blindly subjected to one part of the work, to costumes made by any old dressmaker who strikes a false and foreign note in the production; it is goodbye to the kind of acting, movements, false notes and that terrible, purely literary wealth of details which make modern theatrical production a collection of tiny impressions without that unique simplicity which emanates from a true work of art.”

Specifically, Bakst’s reputation was establishes in the years 1908-09, when he worked as a stage-designer and scene-painter for Greek tragedies, and Diagalev’s Ballets Russes. He produced scenery for their Cleopatra (1909), Scheherazade (1910), Carnaval (1910), Narcisse (1911), Le Spectre de la Rose (1911), L’après-midi d’un faune (1912) and Daphnis et Chloé (1912). During this time, he lived in Western Europe because, as a Jew, he did not have the right to live permanently outside the Pale of Settlement. During his visits to Saint Petersburg he taught in Zvantseva’s school, where one of his students was Marc Chagall (1908–1910).

Bakst’s brilliant control of color, line and decoration give his stage pictures a visual rhythm. Color and chromatic combinations were used emotionally and sensuously—one shade sometimes expressed frankness and chastity, sometimes sensuality, sometimes pride, sometimes despair.

He used primary colors in endless harmonies. Scheherazade created a sense of rich, fevered claustrophobia and mystery. Against the background of closed doors, the dancers became the richly colored ‘brushstrokes,’ creating a living canvas of sensuality and decadence. Scheherazade was a sensation, and Bakst’s designs spilled over into fashion and interior design, sweeping away drab colors and introducing looser clothes.

These he mixed in subtle shadings, say, using the “despair” shade of green with the more intense “despair’” in the blue range. “There are some reds which are triumphal,” he said, “and there are reds which assassinate.” The changing mood of a scene was reflected by introducing colors gradually, visually paralleling the emotion in the text. Serenity could be destroyed by suddenly introducing a violently opposing color, just in a flash of brilliant lining or underskirt.

Surviving Bakst costumes are richly decorated with myriad motifs and decorative shapes. Dense surface textures mix appliqué with painting, dying, embroidery using flocking, floss, beading, sequins, metal studs, braids and decoration, pearls and jewels. Yet, after the designs, the finished costume can seem a disappointment. The bare flesh at midriff, neck, arm and leg is actually well-fitting silk for the principal dancers, cotton for the lower ranks.

This was not just prudery or convention but a practical solution: with three or four contrasting works in an evening, dancers had to change make-up in theatres without proper washing facilities, so restricting the exposed areas to face and hands helped them make fast costume changes in the short breaks between the ballets. Remember that these costumes were seen under stage lights and in movement and audiences certainly ‘saw’ bare flesh.

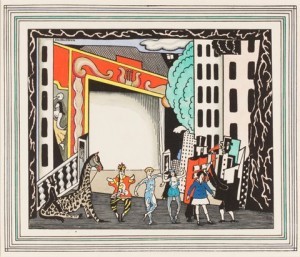

Pablo Picasso’s first collaboration with the Ballets Russes was Parade (1916-17), when he agreed to design the set and costumes. In a letter sent to a friend, Jean Cocteau the librettist said “Picasso amazes me every day, to live near him is a lesson in nobility and hard work”.Picasso’s studio in Rome had a little crate that held the model of “Parade” with its trees and houses, and on a table were the painted characters: the Chinaman, Managers, American girl, and horse. Cocteau described his friend’s unusual artistic process: “A badly drawn figure of Picasso is the result of endless well-drawn figures he erases, corrects, covers over, and which serves him as a foundation. In opposition to all schools he seems to end his work with a sketch.” The poet, Guillaume Apollinaire described Parade as “a kind of surrealism” (une sorte de surréalisme) when he wrote the program note in 1917, thus coining the word three years before Surrealism emerged as an art movement in Paris.

After World War I, Picasso made a number of important relationships with figures associated with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. In the summer of 1918, Picasso married Olga Khokhlova, a ballerina with the troupe, for whom Picasso was designing the ballet, Parade. During the same period that Picasso collaborated with Diaghilev’s troup. He later collaborated with composer, Igor Stravinsky, on Pulcinella in 1920.

Also, in 1920, the painter Henri Matisse was asked to design costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s version of Igor Stravinksy’s opera Le rossignol (The nightingale). In commissioning Matisse and other well-known painters of the European avant-garde, Diaghilev further established Les Ballets Russes as being in the spirit of modernism and artistic experimentation.

This production of Le chant du rossignol was based on the Hans Christian Andersen story of a mechanical songbird presented by the Emperor of Japan to the Emperor of China. Matisse interpreted the orientalist theme and Léonide Massine’s streamlined choreography of the ballet in elegant and dramatically simple costumes and scenery was influenced by Chinese porcelain, paintings on silk and lacquer screens.

This white felt robe for the production’s ‘Mourner’ characters has appliqué geometric spots and chevrons, representing the markings of the Chinese deer, an animal that symbolises longevity in Chinese mythology. The graphic patterns of this costume converted the mourners into a spectacle of abstract shapes.

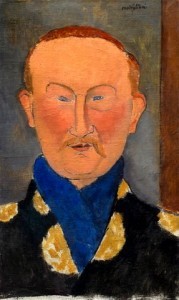

For Nightingale, Matisse and dancer-choreographer Léonide Massine worked together to merge design and choreography. Picasso’s whimsical portrait of Massine as Harlequin is one of several Picasso paintings in this exhibit.

After 1917, Georges Rouault dedicated himself to his Christian faith, informing his work as a painter in his search for inspiration and marking him out as perhaps the most passionate Christian artist of the 20th century. For this reason, the artist may have comitted, in 1929, to create the designs for Diaghilev’s ballet The Prodigal Son, with music by Prokofiev and choreography by Balanchine.

Coco Chanel worked with Picasso, Cocteau, and choreographer Bronislava Nijinski (sister of Vaslav Nijinski) for The Blue Train (1924), a ballet named for the train that connected Paris with the Riviera. Daringly, the ballet brings together the costumes of Chanel with the music of Milhaud and the choreography of Nijinsky,in a witty parody that explores themes of modern sexuality and an emerging body-beautiful culture.

Chanel created its haute couture costumes for swimming, tennis, and golf. She also designed costumes for the famed Ballets Russes prima ballerina Alexandra Danilova.

The designer provided support for Diaghilev and for one of his main composers, Igor Stravinsky, whom Diaghilev termed his musical “first son”. Chanel may or may not have termed Stravinsky her lover, as rumored. Chanel secretly donated 300,000 francs for the 1920 revival of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”, one of the company’s most famous/infamous creations.

Also, Chanel paid for Diaghilev’s funeral and for his burial on the island of San Michele.

The multi-media experience provided by the National Gallery for When Art Danced with Music brings the Diagilev narrative to life, capturing the movement and creative energy of the period and hiss extraordinary vision for what dance could become, once unfettered from its classical roots. A generation of artists, musicians and choreographers were attracted to the stage, both as a vehicle for exercising their creative muscle in a collaborative and highly-visible setting, but also to elevate their position as agents for a new language of expression in the arts.

Recall that the audience rioted during the performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, shocked by its radical departure from classicism, and sending the composer to hide in the wings for his own safety. Now, we casually walk through the National Gallery exhibit, marveling at the dynamics of movement and design that was Diaghilev and his colleagues, wondering what the fuss was all about.

Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909–1929: When Art Danced with Music

On View through September 02, 2013

National Gallery of Art

East Building Mezzanine

Washington, D.C.

http://www.nga.gov

Reposted with permission of Richard Friswell and Artes Magazine.