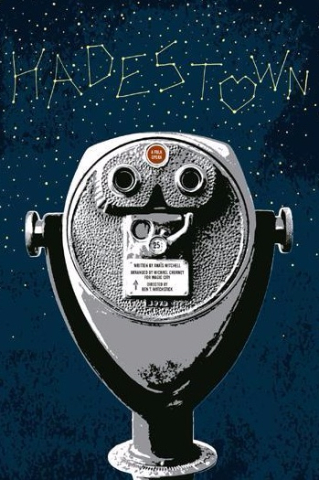

New York Theatre Workshop's Hadestown

To Hell and Highwater with Anaïs Mitchell

By: Susan Hall - Jul 02, 2016

Hadestown

By Anaïs Mitchell

Developed in collaboration with Rachel Chavkin

Co-conceiver Ben T. Matchstick

Directed by Rachel Chavkin

New York Theatre Workshop

New York, New York

Through July 31, 2016

Cast: Nabiyah Be (Eurydice), Damon Daunno (Orpheus), Lulu Fall (Fate), Amber Grey (Persephone), Patrick Page (Hades), Jessie Shelton (Fate), Chris Sullivan (Hermes), Shaina Taub (Fate).

Rachel Hauck (Scenery), Michael Krass (Costumes), Bradley King (Lighting), Robert Kaplowitz (Sound), Todd Sickafoose (Music Supervision), Liam Robinson (Music Director), David Neumann (Choreography).

The compelling Vermont folk singer Anaïs Mitchell, in collaboration with Rachel Chavkin, has created a folk opera, taking the songs she originally wrote and weaving them into an intriguing production by the New York Theatre Workshop.

Picking up the play’s title, Hadestown, the entire theatre on East 4th Street in New York is transformed into purgatory and hell. Only exits at the top of the seating circle lead to the upper world.

The audience sits on hardback chairs of various styles — some of us appropriately closer to hell than others. The purpose of our position is reinforced by a narrator, Hermes, a character who has been added to the story during development. His contemporary recitative is almost rapped as he points out the walls we build, and the sad economic condition of most citizens of this country. "Everybody hungry, everybody tired / Everybody slaves by the sweat of his brow The wage is nothing and the work is hard / It’s a graveyard in Hadestown."

Yet there is an old-fashioned conductor of trains in Hermes. He blows a train whistle and sings: "Hound dog howl and the whistle blow / Train come a-rollin’ clickety-clack Nobody knows where that old train goes / Those who go they don’t come back." Going to hell on a train echoes concentration camps.

Chris Sullivan as Hermes is a hulking and yet delicate presence. His thick, tall body does not inhibit gestures large and small, his fingers pointing, knees collapsing into slouched but secure steps. He reminds of Mac the Knife.

The importance of music as healing is most clear in the beguiling character of Persephone, the wife of Hades, king of the underworld town.

Like Sullivan’s etching of Hermes, Amber Gray is an extraordinarily physical actor. She has Raggedy Ann flexibility in her body, and produces apt, offbeat motions at will. Her head can move like a bobble on her shoulders, she can whirl her arms like a windmill, and dip and tap with and against the band, to whom she gives credit by name in a Second Act call out.

Persephone was chosen as a wife by Hades who wanted her to brighten up the underworld. Gray is radiant in the role.

It is easy to see why the love between Hades and Persephone is reignited by the pure and lovely voice of Damon Daunno as Orpheus. Orpheus prepares for his descent into hell by donning a bright red jacket. Costumes are pointed throughout. Hades and Hermes wear black suits. Persephone is in green silk printed with flowers which adorn her hairdo.

Daunno is also given the most beautiful music by the composer. "Come Home with Me" is only one of many special arias.

Daniel Craig-like, evil-Hades, Patrick Page, is elegant throughout. This elegance helps him to move us. His song, “Hey, Little Songbird,” is at first a seduction of the beautiful Eurydice, and then his tease. When he hears Orpheus sing, he drops tears. It is a remarkable show of emotion which moves him back to his disaffected Queen Persephone.

The first Act moves more briskly than the second in which Orpheus and Eurydice’s hopeful journey to the upper world passes through the audience’s purgatory.

The story of Orpheus and Eurydice was the basis of the first opera written in 1600. It has intrigued artists ever since, from Monteverdi to Christoph Willibald Gluck, to Jacques Offenbach. Dramatists and novelists too have found the tale impossible to resist: Thomas Pynchon, Salmon Rushdie and Tennessee Williams among them.

In the Mitchell/Chavkin take, Eurydice is sent back to Hades when Orpheus glances at her. A hopeful coda suggests that the whole story may be told again, and the outcome different. Of course, it’s difficult not to think of the saying, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Can the Orpheus story be changed in the next go around? This brilliant and moving take on the Orpheus tale makes us want to come back over and over to find out.