Centennial of Surrealism

An Enduring Presence

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 02, 2024

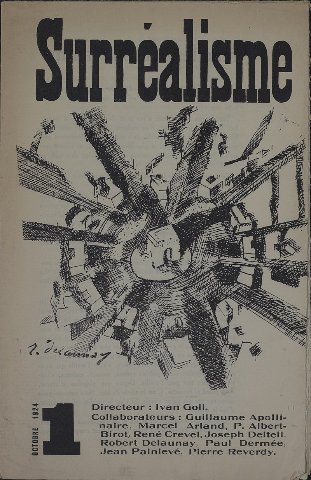

In 1924 in

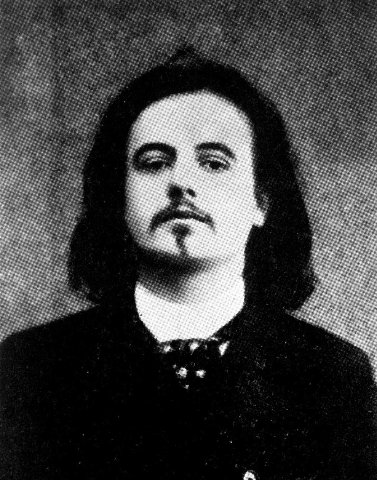

Surrealism initially began as a breakaway faction of the Dada movement, precipitated by arcane philosophical disputes between Andre Breton (1896-1966) and the Dadaist provocateur Tristan Tzara (1896–1963). Both Dada and Surrealism grew out of the same horrified reaction to the butchery of WW1 and fueled by contempt for capitalism and bourgeois propriety.

Reacting to the carnage and spiritual malaise of WWI the Dada movement of absurdity and nonsense was spawned at the short-lived Café Voltaire in 1916 in

Since it had an ill-defined agenda it was an open source concept subject to unique interpretations. Dada was best known for what it was not. That meant a complete rupture from the aesthetics of ever evolving modernism. While isms like Cubism and Futurism derived from Cezanne, Dadaist Francis Picabia (1879-1953) mocked that with a collage portrait of Cezanne as a stuffed monkey.

When mild mannered founder, Hugo Ball (1886-1927), found God and moved to the country a combative poet-agitator, Tzara aggressively filled the breech with raucous screeds of poems, plays and manifestos.

Having bounded about and fueled anarchy in Dada start-ups he moved to

Initially, Tzara joined the staff of Littérature, a magazine edited by Breton. The Dada and Surrealist movements were primarily focused on writers. Breton published images of early works by Giorgio De Chrico (1888-1978) to illustrate his journals while Jean Arp (1886-1966) was often used for German publications.

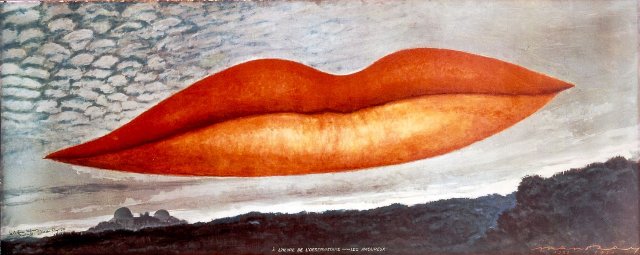

While Tzara was an anti-art, nihilist and anarchist, Breton conceived of an amalgam of Freud and Marx celebrating the subconscious, fantastic and supernatural. Rooted in theory and literature Surrealism evolved to have dream and automatic approaches to fine arts, theatre, music, photography, and film. All of the latter categories informed the work of Jean Cocteau (1889-1963).

During WWI Breton served in a military hospital that treated shell-shocked soldiers. There he absorbed and applied theories of Freud. His approach of dream analysis and the subconscious influenced Breton’s development of Surrealism.

In 1921 Breton presided over a mock trial. The defendant was critic Maurice Barrès, a French anarchist turned right-wing apologist. Tzara served as a witness for the defense. As the trial evolved indictment against Barrès was redirected toward Dada itself. The verdict resulted in the guilt of the co-defendants and death of Dada as a viable movement.

Presiding over the Surrealists Breton was a martinet and grand inquisitor who evoked controversy and opposition. In December 1929, Breton published the Second manifeste du surréalisme (Second manifesto of surrealism), which contained an oft-quoted declaration “The simplest surrealist act consists, with revolvers in hand, of descending into the street and shooting at random, as much as possible, into the crowd.”

In 1930 a collective published pamphlets against Breton, entitled Un Cadavre. The authors were members of the surrealist movement who were insulted by Breton and opposed his leadership.? It marked a rift amidst the early surrealists. Georges Limbour and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes commented on the sentence about shooting at random. Limbour saw in it an example of buffoonery and shamelessness and Ribemont-Dessaignes called Breton a hypocrite, cop and a priest.

The Manifesto had a second edition to which Breton added “While I say that this act is the simplest, it is clear that my intention is not to recommend it to all merely by virtue of its simplicity; to quarrel with me on this subject is much like a bourgeois asking any non-conformist why he does not commit suicide, or asking a revolutionary why he hasn’t moved to the USSR.”

Dada was largely mocked or shunned by critics, collectors and critics. As a non-art movement, entailing works created with found and worthless materials, there was no bottom line for the creators. Nobody got rich from Dada. There are few original works in museum collections. The legacy, however, was rebooted by the similar Fluxus movement which produced artifacts.

In its early years, from 1962 to 1966, Fluxus fused conceptual art, minimalism, new music, poetry, and chance-based work into an intermedia phenomenon. It was identifiable more through its irreverent attitude toward art than through the use of any distinct style. Utilizing humour—in the spirit of Dada—and everyday materials and experiences, Fluxus created original and often surprising objects and events.

By contrast materialism prevailed for Surrealism. Breton expanded the scope of Dada from the fringe to mainstream by embracing some of the most iconic and beloved visual artists of the 20th century. Surrealism sustains, for right and wrong reasons, as one of the most popular movements of modernism.

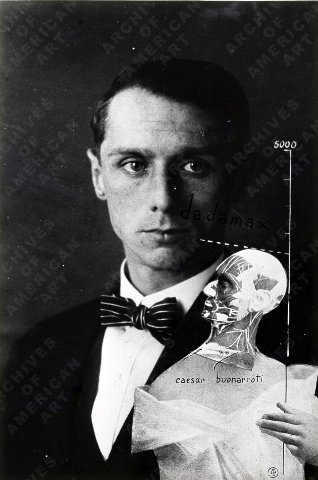

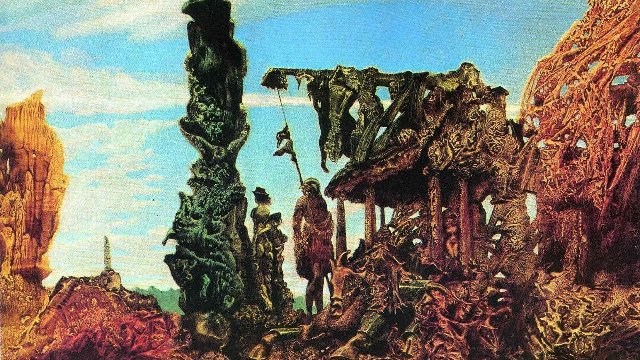

Artists were among those who served in WWI. The Italian Futurist, Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), and Blue Rider artist, Franz Marc (1880-1916) were casualties as was Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876-1918). Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) and Guillaume Appolinaire (1880-1918) sustained head wounds. Otto Dix (1891-1969), Max Ernst (1891-1976) and John Heartfield (1891-1968) were traumatized serving for

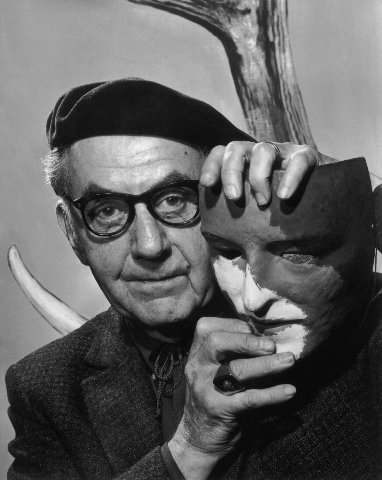

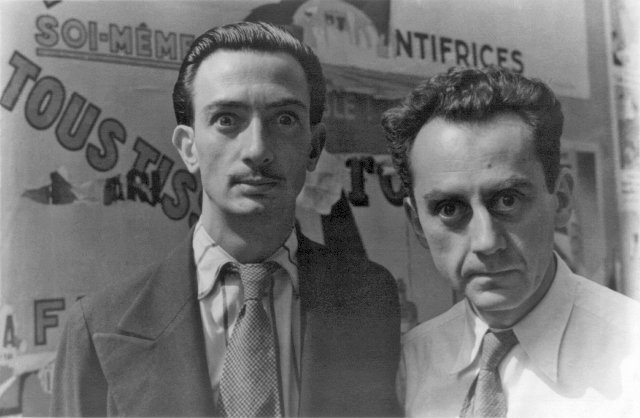

The group led by Goll consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others. Breton claimed that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than Dada. The Breton group grew to include writers and artists Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, René Crevel, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Max Morise, Pierre Naville, Roger Vitrac, Gala Éluard, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Man Ray, Jean Arp, Georges Malkine, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Prévert, and Yves Tanguy.

Duchamp showed with but never enrolled as a Breton surrealist. Similarly, Breton tried his darndest to enlist Picasso. While he made some works in a surrealist manner he ran with other bulls at

An excerpt of Breton’s manifesto states that “The case against the realistic attitude demands to be examined, following the case against the materialistic attitude. The latter, more poetic in fact than the former, admittedly implies on the part of man a kind of monstrous pride which, admittedly, is monstrous, but not a new and more complete decay. It should above all be viewed as a welcome reaction against certain ridiculous tendencies of spiritualism. Finally, it is not incompatible with a certain nobility of thought.

“By contrast, the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole

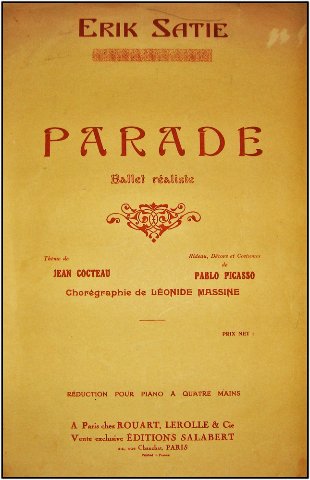

While Goll and Breton battled over naming credit for Surrealism it was coined in 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) in comments regarding the ballet Parade.

Despised by Breton as a boulevardier and gadfly Cocteau collaborated with

Stepanovna Khokhlov (Russian, 1891 – 1955). She attempted to domesticate him while isolating him from his Catalan friends. Under her influence he created in a classical manner producing some of his most lyrical work.

The music, for Parade entailing street noises, was composed by Eric Satie (1866-1925). It was

In a 1917 letter to Paul Dermée referencing Parade he wrote “All things considered, I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used” [Tout bien examiné, je crois en effet qu’il vaut mieux adopter surréalisme que surnaturalisme que j’avais d’abord employé]…

“This new alliance—I say new, because until now scenery and costumes were linked only by factitious bonds—has given rise, in Parade, to a kind of surrealism, which I consider to be the point of departure for a whole series of manifestations of the New Spirit that is making itself felt today and that will certainly appeal to our best minds. We may expect it to bring about profound changes in our arts and manners through universal joyfulness, for it is only natural, after all, that they keep pace with scientific and industrial progress.”

For the next seven years Surrealism was a term in search of a movement eventually anchored by the manifestos of 1924. Which had a somewhat amorphous inception based on admiration of proto-surrealist works of Jacques Vache (wrote letters from the front and a suicide at 24), Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), and the 1868 novel Les Chants de Maldoror, by the Comte de Lautréamont, the nom de plume of the Uruguayan-born French writer Isidore Lucien Ducasse (1846-1870).

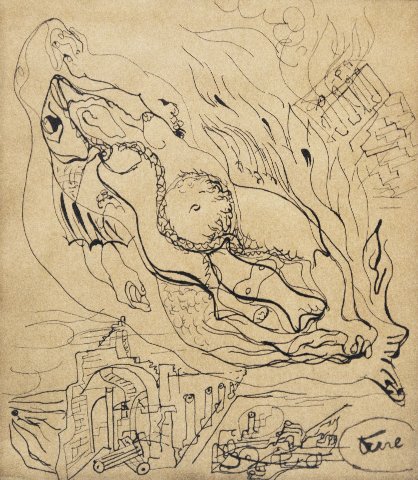

In 1930 Dali was invited to illustrate Les Chants de Maldoror that told a nightmarish tale of an unrepentantly evil protagonist. The book was filled with scenes of violence, perversion, and blasphemy. Dali, who worked in a method he called “paranoiac-critical,” used a stream-of-consciousness process to access hallucinations and delusions.

For the French the arts, particularly theatre, may be regarded as a blood sport. There were riots for Alfred Jarry’s (1873-1907) absurdist “Ubu Roi.” On opening night (10 December 1896), King Ubu (played by Firmin Gémier) stepped forward and intoned the opening word, “Merdre!” Pandemonium ensued: outraged cries, booing, and whistling by the offended parties, countered by cheers and applause by others. At the time, only the dress rehearsal and opening night performance were held, and the play was not revived until after Jarry’s death. There was an American Repertory Theatre (ART) production to which the audience brought vegetables to hurl at the performers.

Picasso acquired Jarry’s revolver. He fired it into the roof of a cab while riding with German gallerists. It’s uncannily similar to the statement for which Breton was censured.

The theatre was trashed during the 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring for the Diaghilev company. Performances organized by Cocteau, Breton and Tzara were routinely disrupted.

There was less overt response to the work of pamphleteers and poets. Breton founded Littérature along with Louis Aragon (1897-1982) and Philippe Soupault (1897-1990). They began experimenting with automatic writing—spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts— published, as well as accounts of dreams, in the magazine. Breton and Soupault continued evolving their techniques of automatism and published The Magnetic Fields (1920).

The poet Paul Éluard (1895-1952), was a man of means and a major player in Surrealism. He is regarded as among the best of the writers who, because of their automatic technique, are difficult to read and comprehend. Afflicted with tuberculosis in 1914 he was hospitalized in the Clavadel sanatorium near

There was another twist when the young Salvador Dali (1904-1989) met Gala. They were immediately inseparable. When he brought her home to

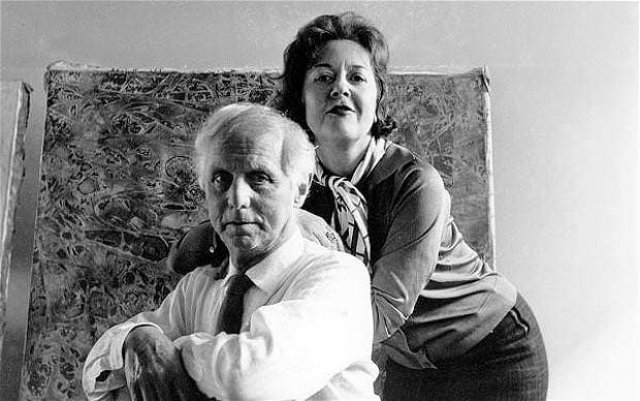

Ernst later married the heiress, collector, and gallerist Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979). She was too busy to keep an appointment with the Surrealist artist, Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012). Ernst went instead and later married her. Guggenheim married several times, had numerous affairs including one with Samuel Beckett (1906-1989), and is said have bedded at least a thousand men.

The first Surrealist exhibition, La Peinture Surrealiste, was held at Galerie Pierre in

In

By 1921 Man Ray moved to

Surrealism arrived in

While Breton and the writers embraced spontaneous bursts of inspiration, initially, it was doubted that this mandate transposed to the more deliberate practice of fine arts. That changed when Ernst developed frottage (rubbing) and Andre Masson (1896-1987) created the first drawings created through automatism. The other form is dream surrealism or the representational rendering of the irrational. The later drip paintings of Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) derived directly from automatism.

To encourage creativity there were séances, trances, and parlor games like Exquisite Corpse. Participants drew an ersatz body part, folded the paper, and then passed to the next person. The sheet was unfolded to reveal a surreal figure.

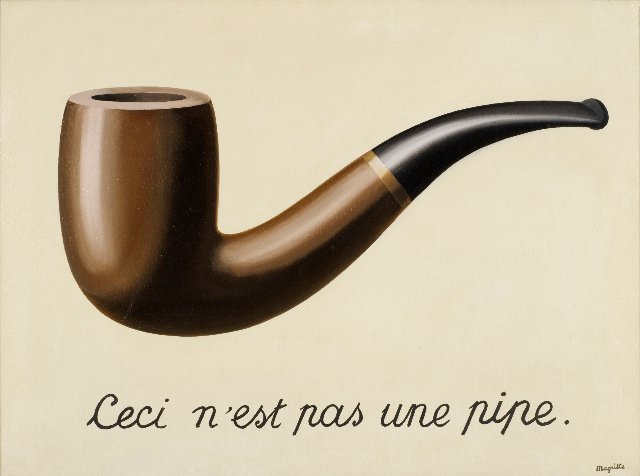

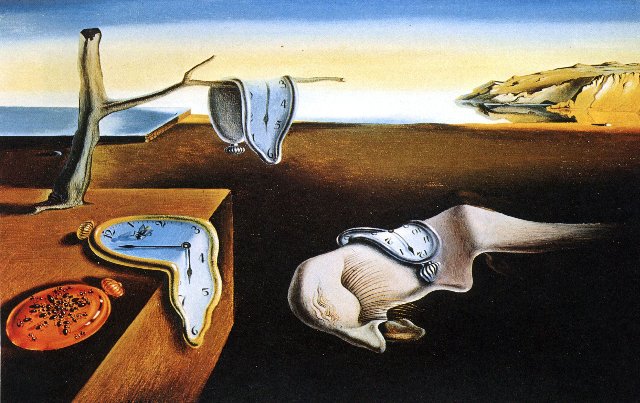

The traditional rendering of Rene Magritte (1898-1967) and Salvador Dali, for instance, conveys to the viewer that, if what is depicted is not real though plausible, hence surreal. In a formal paradigm of modernism, with academic trompe l’oeil technique, they may be regarded as reactionary. It is the manipulation of subject matter that made their work, fresh, challenging, contemporary and timeless.

It was great fun to be tricked into the wit of Magritte some years ago at the

Presumably their next date was the Mets and not the Met.

While the Belgian Magritte and his wife moved to be part of the surrealists of Montparnasse they could not afford

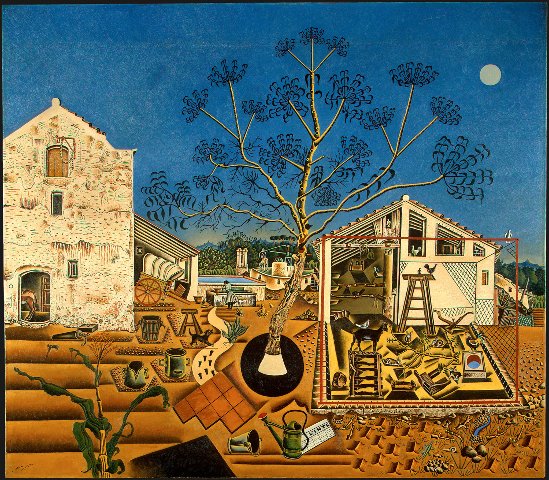

In Spain Joan Miro (1893-1983) developed a more cerebral form of Surrealism. Some years ago I was riveted by a visit to the Miro museum in

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola (1908 – 2001), or simply Balthus, was known for his erotically charged images of pubescent girls and for the refined, dreamlike quality of his imagery. While he belongs in the canon the images suggest a sexual predator and pedophile. For a time, through attrition, he was noted as the greatest living modernist.

Surrealism played a major role in the emergence of abstract expressionism. While the Nazis were advancing toward

She planned to launch a museum in

From

Her father Benjamin Guggenheim went down with the Titanic. When she turned 21, in 1919, Guggenheim inherited $2.5 million. That made her wealthy but poor by comparison to other branches of the family.

During the war years the gallery was a haven for Surrealists in exile. Breton refused to learn English or interact with the American art world. The young, Armenian-born, Arshile Gorky (1904-1948) attended their meetings but was not acknowledged by them. Surrealism, however, informed his experimental work.

There were calls for artists to submit work. Duchamp, a friend and advisor, was interested to see what Guggenheim had rejected. From a stack of

Her first gallery was Guggenheim Jeune in

The NY gallery employed experimental ways to display works with paintings thrusting out from concave walls. They were intended to float in space. Duchamp created a maze with string that guided visitors through the exhibition.

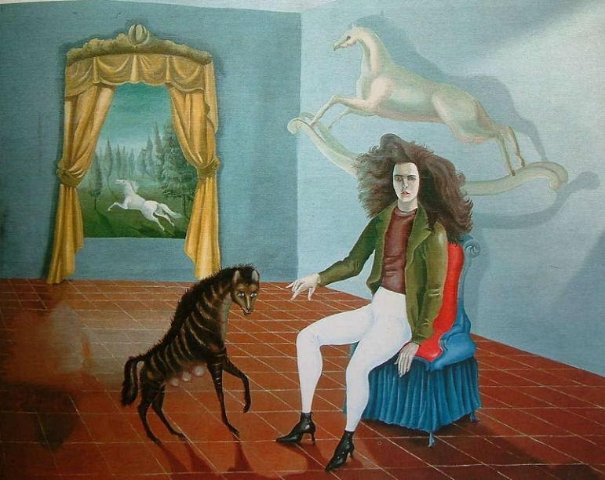

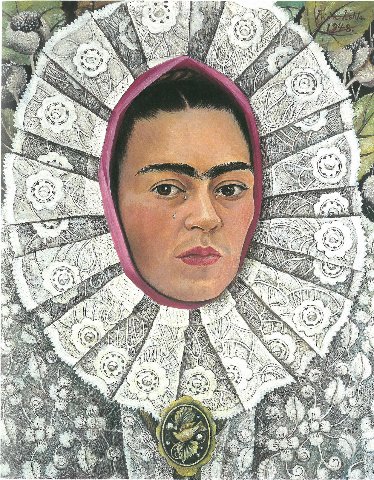

In 1943, at the urging of Duchamp, the gallery featured 31 women artists including Frida Kahlo, Gypsy Rose Lee, Meret Oppenheim, Leonora Carrington, Louise Nevelson, Leonor Fini, Milena Pavlovi?-Barili, Meraud Guinness Guevara, Dorothea Tanning, Kay Sage, Hedda Sterne, Janet Sobel, Xenia Cage (wife of John Cage), Djuna Barnes, Irene Rice Pereira, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hazel McKinley, Pegeen Vail (daughter of Peggy Guggenheim), Barbara Reis, Valentine Hugo, Jacqueline Lamba, Suzy Frelinghuysen, Esphyr Slobodkina, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Aline Meyer Liebman, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Julia Thecla, Sonia Secula, Gretchen Schoeninger, Elizabeth Eyre de Lanux, Meraud Guevara, Anne Harvey, and Milena Pavlovi? Barili. (Without the original check list it’s impossible to verify all of these artists as participants.)

In 2023, art collector Jenna Segal curated The 31 Women Collection, based on the 1943 exhibition. Taking place at Segal’s office, the same location as Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery, the exhibition lasted for 31 hours from May 15 to May 21. Segal aspired to collect works by every artist shown in the original exhibition. 143 works by 30 of the 31 women have been acquired. For further study see Woman Artists and the Surrealist Movement by Whitney Chadwick and Dawn Ades.

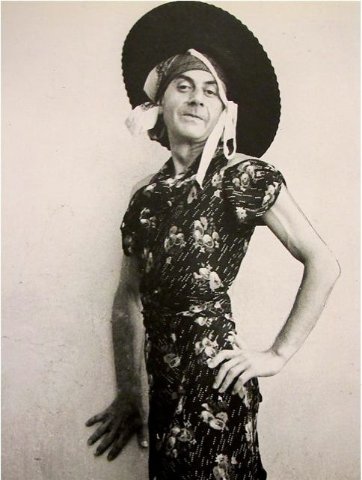

It seems fitting to end this overview with a shout out for Claude Cahun (1894-1954). During the tenure of former

Some 2024 Surrealism Exhibitions

“A Long Affair, Surrealism 1924 to Now.”

June 22 to September 15

Hyde Collection, Glens Falls,

“Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism”

Through July 21 at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts

“Histoire de ne pas rire. Surrealism in

Through June 16 at Bozar, in

“Fantastic Visions: 100 Years of Surrealism From the National Galleries of

Through Aug. 31 at the

“Surrealist: Lee Miller”

Through April 14 at the

“But Live Here? No Thanks: Surrealism + Anti-Fascism”

Oct. 15 through March 2, 2025, at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, in

“Surrealism at the Harn,”

Through June 2 at the Harn Museum of Art, in

“Surrealism From

March 10 through July 28 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; themodern.org.

“Surrealism 100:

April 4 through Sept. 8 at the Eesti Rahva Muuseum, in

“Surrealism: Worlds in Dialogue”

Aug. 31, 2024, through Jan. 5, 2025, at the Kunsthalle Vogelmann, in

“Surrealism So Far”

Sept. 4 through Jan. 13, 2025, at the

“Forbidden Territories: 100 Years of Surreal Landscapes”

Nov. 23 through April 27, 2025, at the Hepworth Wakefield, in