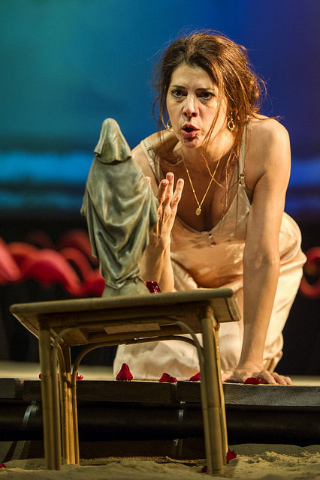

Marisa Tomei in The Rose Tattoo

Williams in Williamstown

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 03, 2016

The Rose Tattoo

By Tennessee Williams

Directed by Trip Cullman

Scenic design, Mark Wendland; Costumes, Clint Ramos; Lighting, Ben Stanton; Sound, Fitz Patton; Projections, Lucy Mackinnon; Original music, Michael Friedman; Dialect coach, Ben Furey.

Cast: Marisa Tomei (Serafina Delle Rose), Christopher Abbott (Alvaro Mangiacavallo), Gus Birney (Rosa Della Rose), Will Pullen (Jack Hunter), Barbara Rosenblat (Assunta), Constance Shulman (The Strega), Lindsay Mendez (Giuseppina/ Folk Singer)

Main Stage

Williamstown Theatre Festival

June 28 to July 17, 2016

The 1951 Tennessee Willliams play The Rose Tattoo is a big sprawling drama with a cast of 24 as well as three kids and a goat.

It is being given a hectic and chaotic production at Williamstown Theatre Festival through July 17. The direction by Trip Cullman is game and feisty but ultimately fails to tame and contain the uneven and occasionally brilliant vision and writing of Williams.

He originally wrote it for the Italian diva Anna Magnani. At the time her command of English was not sufficient for Broadway. The original Serafina featured Maureen Stapleton paired with Eli Wallach. She won a Tony Award for her performance.

Four years later Magnani won an Academy Award for the film with Burt Lancaster as the buffoon Mangiacavallo.

For reasons that become obvious in this ambitiously staged version the play is rarely produced when compared to other of Williams’ enduring works.

The WFT production is a vehicle for the renowned and remarkably gifted Marisa Tomei. Based on her reputation this is one of the most anticipated, must see, plays of the current Berkshire season.

In every sense it takes a village to create the context for the passionate widow tormented and grieving her husband who, for her, was a rose. She has retreated to her home and workshop next to the surf.

There is a sprawling panoramic set designed by Mark Wendland. In a video projection by Lucy Mackinnon, enhanced by the sound design of Fitz Patton, there is the constant sense of waves rolling in on the beach. There is stunning artifice as day transforms into night on the ocean.

The domicile of Serafina is abstracted with a prominent prop of her sewing machine. She earns a modest living as a seamstress and has just created graduation dresses for her fifteen year old daughter Rosa (Gus Birney) and her classmates.

Plans to attend graduation are disrupted when a woman with a swatch of red silk wants a man’s shirt made by the next day. For this she offers an absurd amount of money. The shirt, which was never delivered or paid for, becomes a key prop.

Perpendicular to the stage is a ramp extending through the center of the orchestra. This generates movement through the audience as scenes occurred in our midst. This up close and personal touch provides intimacy with the performers. It is usual to have actors running up and down aisles but this takes that further in the manner of a Super Bowl halftime show.

Williams, who had a tempestuous relationship with an Italian American lover and often traveled in Italy, has charged the play with dated ethnicity and racism that was more comprehensible in the immediate post war era.

With a cute touch that may be taken as offensive the design features a dense row of kitsch, pink flamingos. They may represent a tropical theme but the exotic birds are native to the Florida everglades and not the Lousiana Gulf Coast.

The play is located near Biloxi and not in the delta.

As one of Sicilian/Irish heritage I winced at this semiotic slur as well as offensive language and actions laced through the play. The faith and superstitions of Serafina reek of clichés about Italian Americans.

She prays to the Virgin lighting votive candles to a small effigy. "Send me a sign" she demands of the surrogate during moment of torment and conflict. This is the idolatry that Luther banned from his church. Indeed it is a shock to visit Italian churches with their clutter of crutches left by those who prayed to saints for cures.

The early Roman Catholic Church swapped out pagan gods for Christian martyrs and saints.

There is the Strega character, the village witch (Constance Shulman) who hides among the flamingos and curses Serafina. She casts malocchio or the evil eye. In a wonderful cameo you will recognize her from the cast of Orange Is the New Black.

There is a consigliore character Assunta (Barbara Rosenblat) draped in the black of a Sicilian widow who offers insight and advise to Serafina. She signifies the importance of family, godparents, cousins and bosom friends in Italian society.

By tradition Serafina as a widow should wear black but she never dresses or leaves the house and is seen in a rumpled slip.

During the first act there is a lot going on with so many actors and a chorus of women in perpetual motion that it is difficult to focus on the evolving content.

The point Williams makes is that the reversal of Serafina, and tragic circumstances that have caused her to retreat to a vigil for the spirit of her dead husband, transpires through dynamic interaction with an ethnically charged community.

Ethnicity is precisely what Tomei struggles with. Her dialogue lapses into Italian dialect with its colorful expressions, body movement and gestures, but has not yet been nailed down. An additional week of rehearsals would have helped. At this point her Serafina is more of a parody than performance.

There is another jarring mismatch in the casting of her daughter Rosa. Much is made of the fact that Serafina and her husband are first generation Italians. But the daughter is blonde, tall and slender. She has none of her mother’s earthy sensuality and erotic curves. The mother/ daughter relationship was, accordingly, never plausible.

While most of the first act was awkward and jumbled, by comparison, the second act was simply sublime.

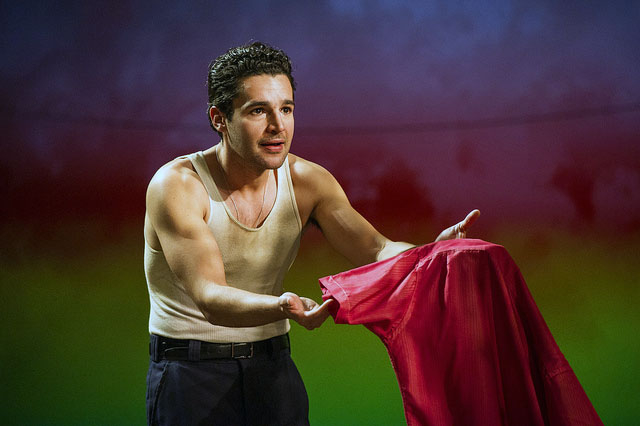

Tomei’s Serefina hits her sweet spot interacting with the superbly cast Mangiacavallo of Christopher Abbott. His performance from accent to body language hit all the right comedic notes.

It is stunning, credible and erotically palpable when she first encounters him. In a vision and miracle The Blessed Virgin Mary has sent her a man with the body of her husband but the face of a simpleton. In the dark it won’t matter.

In Sicily any man of even modest property is a Barone. One who presides over a group of Barones is a Don.

While Serafina was born dirt poor she married a Barone. For this ersatz aristocracy the simple-minded Alvaro addresses her as Baronessa. It is of course absurd but suits his whimsical character. He has delusions of leaving behind three dependents and shacking up with a woman of property who has her own business.

Like her late husband he also drives a banana truck but has no hidden cargo.

In an altercation over road rage with a racist, cracker traveling salesman (Darren Pettie) he has just been sacked. During this exchange Williams unleashes every possible n-word equivalent for Italians.

Those were words I heard when visiting the South during the 1960s. It was when I put a hurt on a summer neighbor foolish enough to call me a WOP.

Although Serafina carries the torch, or more literally lights candles to her beatific dead husband, the village knows otherwise about his philandering.

He was a man of deception with something hidden under the bananas. It seems he also made house calls.

There were a number of near climaxes in their heart warming and perfectly played courtship. But Williams also wants to resolve the subplot of the coming of age of her daughter.

With suitable and often delicious twists and turns Serafina find sex and happiness in the arms of the direct descendant of the village idiot. While Rosa gets what she wants as well.

They sail off into the sunset past all those friggin’ flamingos.