Wagner's The Flying Dutchman in Zurich

Anja Kampe, Bryn Terfel and Matti Salminen Star

By: Susan Hall - Jul 06, 2013

Der Fliegende Holländer

by Richard Wagner

Zurich Opera House

Zurich, Switzerland

Conducted by Alain Altinoglu

Producer Andreas Homoki

Philharmonia Zurich

Chorus of the Zurich Opera

Wolfgang Gussmann (Stage Design and Costumes), Susana Mendoza (Costumes), Franck Evin (Lighting), Jurg Hammerli (Chorus Master), Werner Hintze (Dramaturg).

Anja Kampe (Senta), Liliana Nikiteanu (Mary), Bryn Terfel (Hollande), Matti Salminen (Daland), Marco Jentzch (Erik), Fabio Trumpy (Steersman) Nelson Egede (Daland’s servant).

Coproduction with La Scala, Milan and Norwegian State Opera, Oslo.

July 3, 2013

“Opera should be relevant to our lives today, not some dusty affair,” says Andreas Homoki, the new general manager of the Zurich Opera and the producer of the current Flying Dutchman." Overture

This Dutchman dances on a thrilling high wire act, driven first and foremost by the brilliant musical and dramatic talents of its three principals, Matti Salminen, Bryn Terfel and Anja Kampe.

Salminen is almost 70 and one of the those performers, like Melchior, who deserves go on forever. Masterful a little over a week ago in Budapest, where he was a riveting Gurnemanz, he relishes his role as Daland, the sea captain who brings Hollander home to wed his daughter. He wrings his hand with greed at the prospect of gaining Hollander’s vast wealth, even though the consequences of this alliance may be disastrous for his beloved Senta.

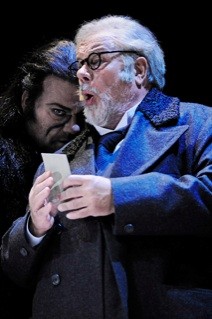

Step for step and note for a note Salminen is a match for the great Bryn Terfel, who seamlessly fits the Hollander role. Costumed in a long, rough fur coat and looking like a bear or even the beast ready to meet his beauty, Terfel terrifies in his madness and mesmerizes in his soft passionate passages. When Senta accepts him and his curse, he strips off his coat and reveals very much a man, although a clever, black half mask drawn on his face is still there, reminding us that the curse has not evaporated.

Anja Kampe is a great Wagnerian heldin soprano. Her big, richly textured tones in the mid-range and her blazing top herald an important star. She is also a consummate actress, nominated for an Olivier for the acting in this role.

Typewriters and telephones were developed at the same time African colonialism flourished and these images dominate the props on stage. Daland’s crew are managing from an office, abuzz with telephones. The spinning scene is now whirling typewriter ribbons in the back office, where the typing pool mercilessly tease Senta, who dashes about the stage, casting off their barbs, while she clutches a picture of her romantic hero, the Flying Dutchman of myth.

This staging gives Senta a chance to join the action instead of sitting and gazing at a picture hung on the wall, the usual approach. And Kampe is an actress who exceeds one’s wildest opera expectations, so she takes full advantage of the staging offered to her.

Ava Gardner once played the role in film, and her statue rises above the shore in the Spanish town where the film was shot. Kampe deserves a statue in her honor too. (She, incidentally, a beautiful woman, angelically Nordic).

Fabio Trumpy added a wonderful ring to the Steersman’s aria about the lass waiting at home for him. In the thankless role of Erik, the good man who women never prefer over bad boys like the Hollander, Marco Jentzch has to moan ‘woe is me,’ and whimper ‘Do you no longer remember the day you asked me to visit you in the valley.’ Yet in this duet with Senta, remembering the happy times when he picked flowers for her in the mountains, his voice and posture were delightful.

Alain Altinoglu conducted with authority, making the most of the lighter sea chantey tunes and embracing the deeper leitmotifs which make this opera the first of Wagner’s mature works. From the overture’s first stark, fierce chords in the woodwinds and strings, we are plunged into the raging sea as the Hollander’s theme blares forth in the horns.

The set is really terrific. Changing from the offices of the sea captain to his home, the turntable moves naturally. But when the ghostly blasts of the Hollander’s winds blow against the chorus as office workers, the set moves. They push against it revealing just how difficult he is to resist.

A portrait of the sea, which comes to life with the blood red sails, and the black masts of the Hollander’s boat serve the water element well. A map of Africa reminds us of the Hollander’s curse: he had blasphemed when he swore that he would round the Cape if it was the last thing he accomplished.

Above all, this production is opera for the soul. Dusty is a word that would never come to mind. Drowning, passionate, the sense that extreme love can only be fixed in another world, all of these, performed magnificently, make a perfect opera evening. The piece was mounted without intermission, as Wagner wrote it. Real time is marked by a wall clock in the stage offices. Concentrating for two and a half hours on greatness was a particular treat.