The Lifespan of a Fact

Do Facts Constitute Truth? Is Truth Objective and Unassailable?

By: Victor Cordell - Jul 06, 2024

It seems to me that when we were kids, our simple world of morality was comprised of truth and lies, with the special category of white lies. Especially in our current political environment, there seems to be an unlimited menu of colorations and characterizations, from truthiness to alternate reality, with an increasing hesitancy to call even the most egregious untruth a lie.

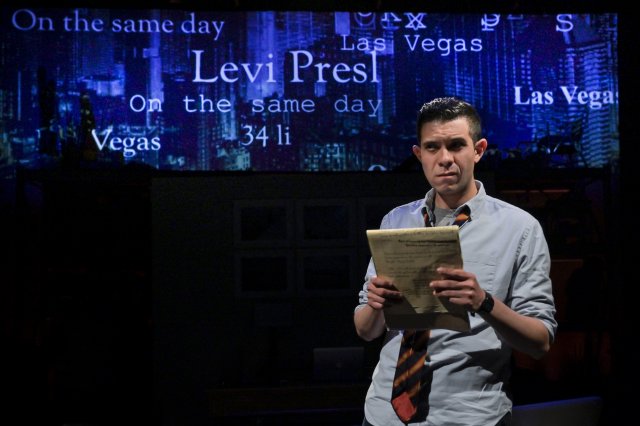

Into the real-world cauldron of etymology and principles comes John D’Agata, an essayist who writes a piece on the suicide of Levi Presley, a 16-year-old boy who leapt to his death with a 1,149 foot fall from the observation platform of the Stratosphere Hotel in Las Vegas in 2002. When the author took his manuscript “What Happens There” to The Believer, a distinguished journal of essays, reviews, and interviews, an intern fact checker, Jim Fingal, was assigned to the project.

A seven-year tooth-and-nail battle over facts ensued between the two men before the essay was finally published. They documented their saga in the book “The Lifespan of a Fact” (itself a curious title), which is fact-check annotated. This was adapted into a play of the same name, but with generous doses of literary license (untruths), most importantly, compressing the timeline into several days. The result is a provocative discourse on the slipperiness of facts. Aurora Theatre’s taut and riveting production will provoke endless thought and discussion.

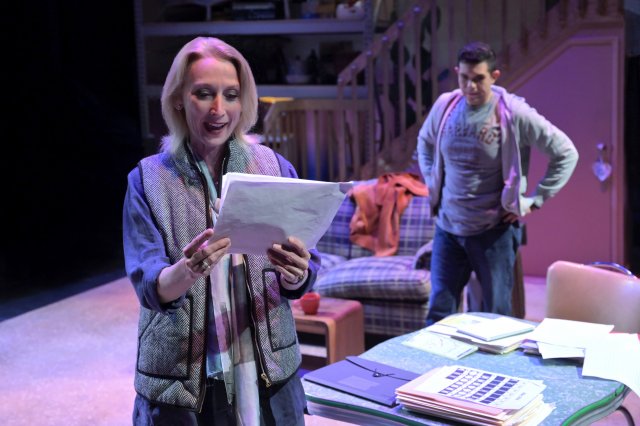

In this three-character production, stalwart Carrie Paff is Emily, the magazine editor who has sacrificed family to pursue career. Paff convinces as a professional whose goals are to produce quality articles of interest; to meet deadline; and to ensure that editorial procedures protect the magazine from being sued. Hernán Angulo is Jim, an overwrought intern in his first fact-checking assignment, who wants to prove that he can be accurate and thorough. But among the first overriding questions in the narrative is how he interprets his charge. What is he actually meant to do? Finally, Robert Parsons is John, condescending, self-serving, and sarcastic. Parsons is the understudy in this role, but he is a first-class actor with a significant resume of leading roles, and he fits the part exquisitely, extracting laughs from every acerbic comment.

Clearly, different grades of mendacity exist. We live in a world in which some amoral politicians no longer bend facts but break them to their advantage and to break their opposition, often through contrived falsehoods. And supporters totally suspend their moral convictions in cultish awe of their leader.

John is merely an embellisher. He knowingly distorts information but does so in what he considers the service of the greater good, to make a story more interesting and to promote its underlying value. If the rhythm of the number four satisfies more than the number one, he will replace the latter. If a numerical countdown of relevant incidents provides more drama, he will manipulate the facts to fit the device, but with no harm intended. As he duly notes, a well-crafted story told at the right time can change lives. He will even justify making up a scenario to support his “truth.” But though Emily can give innocuous fact-shifting a pass, she draws the line when she sees possible liability for the magazine. For Jim, a fact is a fact, and he will confront even the least consequential manipulation.

The narrative triggers thoughts about facts and truth. The viewer is confronted with a host of issues. What constitutes a fact? John gives the example of the coastline of Britain. The length depends on how it is measured, how deeply the measurement goes into estuaries. Do facts get in the way of truth? And what is close enough? If John writes that Levi fell to his death for nine seconds, but it was closer to eight, is his statement unfactual?

Perhaps the most unsettling concern in today’s world is the permissibility of attribution to justify a statement. For instance, John’s source for a provably inaccurate but unimportant scenario in his manuscript was a homeless person. With the ubiquitous sweep of social media, it is now possible to find every opinion imaginable on the Internet, and the cynic may forward or paraphrase what they absolutely know is a lie. If confronted about the veracity, they defend themselves by saying that they saw online. This moral mudslide leads to the worst manner of misinformation and conspiracy theory.

The first 30 minutes of this 90-minute production are a bit uninvolving. Director Jessica Holt has Angulo playing Jim over-the-top, presumably to give energy to the early going. But as a bottom-of-the-totem-pole intern, his sass and disrespect for the editor simply doesn’t ring true in the real world. Happily, the remaining hour, which corresponds with the first appearance of John, is fully engaging. The acting is powerful; the pace is invigorating; and the issues are absorbing so that many a discussion will be had by theatergoers on the way home from the performance.

“Lifespan of a Fact,” written by Jeremy Kareken & David Murrell and Gordon Farrell is based on the book by John D’Agata and Jim Fingal, produced by Aurora Theatre, and plays on its stage at 2081 Addison Street, Berkeley, CA through July 21, 2024.