Lithuania: Part Two

Klaipeda and the Curonian Spit

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 10, 2015

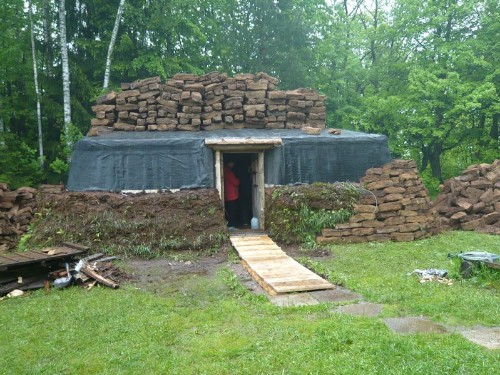

On our way to Klaipeda we visited the Rumsiskes Open-air Ethnographic Museum. Lithuania has five ethnic regions with different dialects, textiles, and housing styles. To an area of 500 acres the museum has transported 150 18th- and 19th-century rural farmsteads and dwellings, 120 of which are authentic wooden houses; the remaining 20 are brick replicas. 27 of the houses are open to visitors; we visited about eight of them from the highland, southwest, and lowland regions, the latter having bigger rooms. The interior of each house represents the traditional lifestyle of its region. There is also a 19th-century church on the premises. After visiting a weaver’s workshop, we stopped by to see Irene, a survivor of deportations in the 1940s, and a dwelling used by Lithuanians who were deported to Siberia by the communists.

Irene shared her memories of the time she spent as a child by a scary cliff on a forsaken corner of Siberia, where both of her parents perished. 28,000 of the 132,000 Lithuanians deported died of hunger and slave labor. Survivors were deprived of the right to return until the issue of a decree from the Supreme Council of the USSR on 7 January 1960. An exhibition of winning works of the national student contest “History of the Struggle for Freedom and Losses of Lithuania” was the backdrop of Irene’s presentation.

Lithuania’s history continued to reveal itself upon arriving in Kaunas for a lunch break. Kaunas was the provisional capital of the country for over two decades while Lithuania fought to reclaim Vilnius from Poland after World War I. The country’s second largest; the historic city is an architectural treasure, with the stone-paved streets of the Old Town and Market Square. Liberty Avenue is lined with 16th-century houses.

Klaipeda is Lithuania’s oldest and third largest city, with a population of 180,000. It was founded by the crusaders in 1252 as Memelburg and has been sought after by kingdoms and empires throughout history due to the strategic position of its ice-free harbor on the Baltic Sea. Klaipeda was a German city in the 19th century until the Soviets arrived in 1923, changing even the historic cobblestones. It has the only seaport and cruise ship dock in the country, and is therefore heavily used by the timber industry and visited by cruise ships. About 20% of the population are native Russian speakers.

The National Hotel was our home for two nights in Klaipeda, the gateway to a coastal stretch known as the Curonian Spit, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the primary reason for our visit. A narrow and lengthy peninsula — 60 miles long, 5 miles wide — separated by the protected Curonian lagoon on one side and the Baltic Sea on the other is shared by Lithuania and the Kalingrad region of the Russian Federation. The picturesque strip of sand is home to several fishermen’s villages; we took the car ferry to Nida to look for amber along the shore.

Amber is fossilized resin of pine trees dating from 50 million years ago, when the Baltic Sea used to be a forest. Fossilized resin laid underground was repossessed over time and polished by the sea, ultimately washing up on the beaches during winter storms. A symbol of Lithuania, Baltic amber is known for its colorful palette. Bluish amber, the result of iron in the fossilized resin, is the rarest and most valuable. It also comes in white, red, and transparent shades, the latter being the most frequently found on the beaches.

By way of a planked stairway we climbed over the dune and descended to a windy beach. Wind breaker zipped up, hood tightly tied under my chin, and wearing gloves, I began my hunt for “Baltic gold,” as it is known in Lithuania. By looking closely at the clumps of seaweed that had washed ashore, I spotted a small piece that glistened amidst the wet dark leaves tangled up with sticks. Thus encouraged to continue despite the chilly weather, within half an hour I was able to find a small handful of amber, ranging from tiny pieces to the size of a pebble. One of us lucked out and found a relatively good-sized piece of amber, big enough to have set as jewelry. Vita confirmed that this was a rather unusual find, as big pieces are usually excavated from the depths of the Baltic Sea.

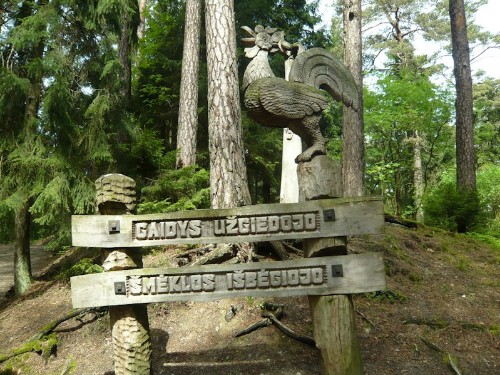

Stashing our “Baltic gold” in our bags, we then hiked through a meandering forested slope through the dunes to Witches’ Hill, where Lithuanians used to celebrate the shortest night of the year until the event was disrupted by World War I. The summer solstice was a time to believe that witches would be around and to be aware of their spells, lest they bring harm such as drought, flood, or hail. This special place, somewhere between the mystical and the real world, has been revived since 1979 by craftsmen invited to carve personalities from century-old legends. Starting out as 20 works by folk artists, the ensemble has now grown into 80 oak sculptures. The legends range from the Birth of Neringa, responsible for creating the sand strip that divides the sea from the lagoon, to the Water Sprite, protector of the lagoon, who keeps it from drying out. The cock crowing at dawn ends the night; witches run away — all in all a delightful place to visit.

Upon our return to the shore, another delightful sight was treetops studded with bird nests. The Curonian Spit attracts a variety of birds, the largest colonies being of grey heron and cormorants, species that feed on fish and use trees for incubation. Cormorants lay nests on treetops; herons build them on branches alongside trees. Nearly extinct in the rest of Europe, cormorants have resettled here and have rapidly increased their numbers to 3800 birds. Storks begin coming from Africa — a 6000-mile flight — in late March and leave at the end of August. Storks six years and up begin to couple and build nests. People set up circular metal frames on top of utility poles to make nest-building easy for the birds. The stork is the national bird of Lithuania.

Lunch was in Kursmariu, the private tavern of a local family by the seaside, where we enjoyed pike-perch. The owner, a spirited Lithuanian, sang for us at the end of the meal and invited us to join her at the microphone. Following a good time, we drove up to the Parnidis Dune, where it was possible to view both the Baltic Sea and the lagoon. A contemporary sun clock-calendar, based on traditional understanding of a sundial, tracks the sun as it rises from the lagoon and sets into the sea.

On the way to an amber workshop and gallery, we passed by a block of apartments built by the Soviets, the ground floors of which are now occupied by shops and galleries. Built as workers’ homes, the five-story apartment buildings accommodating 50 families each, average 500 square meters with small windows and no elevator. Vita explained that no private homes had been allowed at the time; she had lived with her parents in one room of a shared four-room apartment.

At the amber workshop in Nida, we each chose a small piece of amber already threaded with a piece of string to wear around the neck. After sanding the amber into a smooth piece, we polished it and were told to keep it as a souvenir, along with a certificate acknowledging our newly acquired expertise. The gallery had amber jewelry for sale in display cases. Baltic Sea amber has a large amount of acid since the resin takes so long to develop. Therapy centers offer a variety of amber treatments and cosmetic products. Amber tea, incense, and soap are also available in specialty stores.

On the way back to Klaipeda, Vita continued to inform us about her country. Russian oil is refined in Lithuania; industrial lasers, biotechnology products, timber, textiles, and ready-made clothing are among the country’s exports. Apples are the only locally grown fruit, but there are huge fields of wheat, barley, rye, and rapeseed. Most vegetables are imported; dairy products along with meat — beef, pork, chicken, and ostrich — are plentiful. Vita concluded by explaining the symbolism of the bands on the Lithuanian flag — yellow for the sun and wheat fields; green for the forests and red for all the blood shed.

In the morning we started our journey toward Latvia with couple of noteworthy stops on the way. The Hill of Crosses is a mound covered with some 200,000 crosses placed by people to show their love and gratitude to God. Beginning with 30 crosses in the 19th century, the hill also became a place to commemorate heroes who died during revolts, as well as a symbol of resistance to the Tzar. During the Soviet period, the authorities tried to demolish the crosses, but new ones quickly replaced them. In 1993, Pope John Paul II visited the Hill to celebrate Mass during his apostolic trip to Lithuania; the Pope’s cross graces the entrance to the mound. A contemporary church nearby is positioned so that one sees a mirror image of the mound in the large altar window; from the inside, the window frames a large cross with a sweeping view of the hill as backdrop. Cross-makers are some of the most respected people in Lithuania.

For lunch at a traditional restaurant in Siauliai we enjoyed chicken croquettes served with roasted potatoes and mixed vegetables. The dessert, which Vita referred to as “lazy cake,” requires no baking and is made by mixing softened butter with broken pieces of biscuits, then flavoring it with sweetened condensed milk and cocoa. Shaped in a loaf pan, the cake is chilled and served with ice cream — decadent but delicious. Afterwards, a cup of special tea made from a blend of seven herbs, accompanied by a shot of Benedictine, prepared us for a nap back on the bus!

Unfortunately, the bus broke down as the driver was backing out of the restaurant’s parking lot; after a few phone calls we were told another bus was on the way. Meanwhile we decided to walk about the city of Siauliai. Walking down the main boulevard, we noticed the library; the two librarians in the group suggested we go in to say hello. The library turned out to have an American corner with an English-speaking coordinator. She welcomed us and pointed to a large map of the United States on the wall, dotted with push pins on all the cities where American visitors had come from. We also visited the children’s area of the library, where there were a large section of books in English — very impressive indeed.

Finally back on the bus, we were on our way and looked forward to our first stop in Latvia — the Rundale Palace Museum and Park.