Dance Theatre of Harlem at Jacob’s Pillow

Conflating Classical Ballet and Post Modernism

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 12, 2014

Dance Theatre of Harlem

Founders, Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook

Artistic Director, Virginia Johnson

Executive Director, Laveen Naidu

Dancers: Lindsey Croop, Jenelle Figgind, Ashley Jackson, Nayara Lopes, Stephanie Rae Williams, Fredrick Davis, Dustin James, Dylan Santos, Samuel Wilson, Chrystyn Fentroy, Emiko Flanagan, Alexandra Jacob, Ashley Murphy, Ingrid Silva, Darius Barnes, Da’Von Doane, Francis Lawrence, Anthony Savoy

Jacob’s Pillow Dance

July 9 to 13, 2014

Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven: Odes to Love and Loss (1993)

Choreography, Ulysses Dove

Staging, Anne Dabrowski

Costume Design, Jorge Gallardo

Lighting design, Bjorn Nilsson, recreated by Peter D. Leonard

Past-carry-forward (2013)

Choreography, Tanya Wilderman-Davis and Thaddeus Davis

Music, Willie “The Lion” Smith, and SLIPPAGE (Thomas F. DeFrantz and Jamie Keesecker)

Dramaturg, Thomas F DeFrantz

Costume design and execution, Charles Heightchew

Lighting design, Paul Jakubowski and Peter D. Leonard

Contested Space (2012)

Choreography, Donald Byrd

Music, Amon Tobin

Lighting Design, Peter D. Leonard

Assistant to the choreographer, Jamal Story

In 1955 Arthur Mitchell became a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. Inspired by the turbulence and struggle for civil rights in 1968, with his mentor and dance instructor, Karel Shook, he founded a school to teach classical ballet to young people in his native Harlem.

This served the dual purpose of bringing high culture to the community while providing young people with the disciple and opportunity to bring focus and hope to their lives.

Just two years later Dance Theatre of Harlem made its Jacob’s Pillow Debut and has returned frequently since then. It opened the season last year and has returned with a new program of three pieces with two intermissions.

By continuing the demanding classical training and techniques introduced by Mitchell the company addresses an unique challenge. It is both rooted in traditions that started in the French court and flourished in Russian ballet and also creates dance that reflects contemporary style and culture.

As we experienced last night in Becket that’s a difficult balance that doesn’t always work. In three different works the company demonstrated its range and diversity of stylistic approaches but often felt restrained, academic and enervating. While superbly disciplined, with women performing en pointe, a feeling of formalism prevailed rather than the energy, freedom and inventiveness that we associate with the best contemporary dance companies.

That mood of solemn restraint was established with the first piece, an elegy of loss, by Ulysses Dove, the most renowned African American choreographer of his generation who died of AIDS mid-career at 49.

The piece Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven: Odes to Love and Loss was created in 1993 at a time when the arts community was devastated by AIDS. Including family members he was motivated by the loss of thirteen loved ones. He stated “I want to tell an experience in movement, a story without words and create a poetic monument over people I loved.”

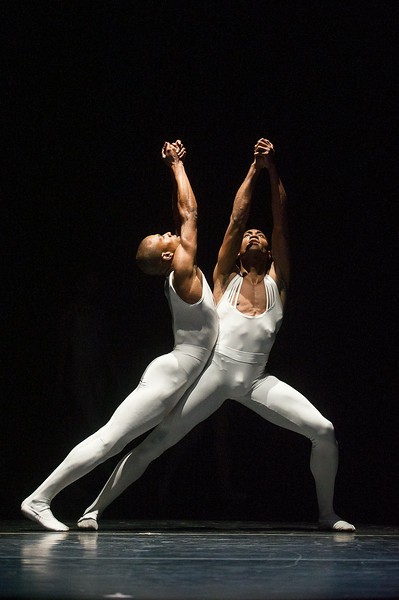

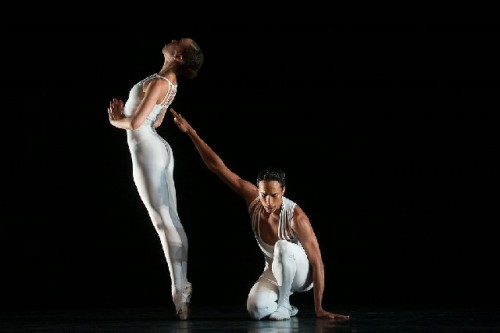

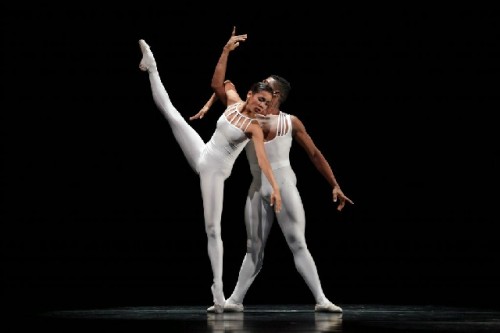

A bell tolls as we encounter six dancers, three male and three female, costumed in form fitting white, in a circle. During the course of the dance, including the finale, they will regroup with more bell sounds defining movements before breaking off into combinations of duets, pas the trois, and solos.

There is an often slow, austere, dignified restraint as variations signify individuals and relationships including, significantly, male partnering with intimate touching.

The piece was created for the Royal Swedish Ballet and has been performed at Pillow several times by different companies. It was moving and appropriate to see this version by DTH.

The second work past-carry-forward in its Pillow debut comprised two less than seamless segments. The first was a narrative capsule depicting the great migration of blacks from racism in the South to urban settings. This is seen literally with a couple boarding a train headed north. Then we catch a glimpse of jitterbugging Harlem night life. This evolves to African Americans in the segregated military during WWII. Then a return home to demeaning roles as Pullman porters and entertainers.

This part of the program was most upbeat and absorbing for the audience. One could follow the story line and enjoy the jazz based music. But there was an annoying trope. To get the old timey feeling of 78 rpm recordings there was a scratchy needle sound. No remastered Hi Fi here. This device was amplified and sustained to the point of being distracting.

Just when we were having fun the mood changed with a switch to contemporary avant-garde music and costumes to match. If you were following the narrative line the intention was to bring us into the present. In an artistic sense, however, this proved to be changing horses mid stream. It left the audience disconnected from two very different dances which should have been separated at birth.

The final selection Contested Space, choreographed by Donald Byrd to digital beat music by Amon Tobin, underscored the conundrum of conflating past and present. The costumes designed by Natasha Gurleva were fresh and fun combining neutral grey with dashes of bright red as a sash or brooch.

The dance started with a supine male acrobatically coming to this feet. Eleven men and women formed groups on either side of the stage. Initially they titubated in place to the incessant beat of the music. Then pealed off in combinations. Typically a male dancer traversed the stage, took a right angle turn forward, stopped, then executed an elaborate solo followed by partnering.

As the piece progressed there were absorbing moments, particularly the complex lifts and flawless pirouettes, but also a sameness. In being sustained beyond poignancy the piece became repetitious and enervating. This is an instance where less would have been more.

The evening left us with mixed responses. Clearly this is a company justly admired for its discipline, classical training, and historic mandate. But it also evokes a dilemma. There are companies that sustain the classical traditions that Balanchine brought to American dance. That’s where DTH seems to derive its style. It's unclear where it resides in an American vernacular.

The program conveyed mixed messages of trying to move on while sustaining ballet and its traditions yet embracing contemporary music and style.

Overheard during intermission as one man put it to his friends “I am enjoying the dance but I can’t make up my mind. For me it’s ballet but too modern.”

There’s nothing wrong with that. The trick is to make it work.