Dance Theatre of Harlem

50th Anniversary Performance at Jacob's Pillow

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 12, 2019

Dance Theatre of Harlem

Founders: Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook

Artistic director: Virginia Johnson

Executive director: Anna Glass

Ballet master: Kellye A. Saunders

Dancers: Derek Brockington, Lindsey Croop, Kouadio Davis, Da’Von Doane, Yinet Fernandez, Alicia Mae Holloway, Alexandra Hutchinson, Dustin James, Choong Hoon Lee, Daphne Lee, Christopher Charles McDaniel, Anthony Santos, Crystal Serrano, Ingrid Silva, Amanda Smith, Anthony V. Spaulding, II, Stephanie Rae Williams

Harlem on My Mind

Choreography: Darrell Grand Moultrie

Music: Count Basie Orchestra, Chris Botti, Wynton Marsalis Jazz at Lincoln Center with the LA Philharmonic

Costumes: Rebecca Turk

This Bitter Earth

Choreography: Christopher Wheeldon

Music: Clyde Otis performed by Max Richter and Dinah Washington

Costumes: Katy Freeman

Valse Fantasie

Choreography: George Balanchine

Music: “Valse Fantasie in B Minor” by Mikhail Glinka (1839, orchestrated 1856)

Costumes: Larae Theige Hascall (special arrangement through Pacific Northwest Ballet)

Balanouk

Choreography: Les Yeux Noirs, Lisa Gerrard, Rene Aubry

Costunes: Mark Zappone

Fifty years ago, a former New York City Ballet principal artist, Arthur Mitchell (1934-2018) and ballet master Karel Shook, inspired by the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., founded Dance Theatre of Harlem. Using his own savings the mandate for Mitchell was to bring training of classical ballet to the African American community. DTH soon grew to enroll some 500 students. Mitchell purchased and renovated a garage which still serves the company.

In 1970 DTH made its first visit to Jacob’s Pillow. They return this week on the occasion of their 50th anniversary. Mitchell was involved in preparation for this event which he did not live to see.

Both Mitchell as a performer and the company he co-founded, endured many obstacles. With the company of George Balanchine he performed all of the leading roles. Balanchine created the pas de deux in Agon especially for Mitchell and Diana Adams. Audience members initially complained about partnering Mitchell with a white woman, but Balanchine refused to change the pairing. They performed the work all over the world.

When DTH was formed Balanchine gave permission for the company to perform his works. Mitchell, for his part, taught Balanchine’s technique as the defining signature of the company. DTH used that discipline to conflate other traditions reflecting the broad reach of African American and Caribbean music, culture and dance.

The fruition of that pedagogy was evident last night in a diverse, accessible, technically brilliant and lyrical program. Through four works in two acts we got a strong sense of the range of the company.

The appearance also represents resurrection and reconstitution. Through a tough combination of financial and administrative setbacks there was a hiatus (2004-2012). When a founding dancer of the company, Virginia Johnson, became artistic director there was a need to rebuild from scratch.

There was no longer in place the generational mentoring of what had been a family of dancers. Where there had been 50 dancers now there are eighteen. That represents a rupture of institutional memory and the renowned repertoire required complete revision.

The reborn company needed to be trained. From their strengths new works were commissioned as well as standards revised. Until his death, last September, Mitchell was essential to the aesthetic transition.

Much to the credit of the commitment and resilience of DTH under Johnson what we experienced was an exquisite triumph.

The evening began with Harlem on My Mind a tasty buffet of the company at its most joyously accessible. The exuberance of the dancers, with megawatt smiles electrified the performance. We saw the company at its very best by bringing classically inspired discipline and dance to a range of superb jazz performances.

In colorfully mottled costumes designed by Rebecca Turk there was both ensemble work as well as solos by male and female dancers. The music started with the Count Basie Orchestra from the later period. They performed the less familiar “Idaho” then a send up of the Fats Waller standard “Ain’t Misbehaving.” Then oddly, as they were friendly rivals, Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got that Swing.” The Basie version was brassy where Duke was notable in scoring for the reed section.

There was a stunning solo to Chris Botti performing the ballad “My Funny Valentine.” While Botti brings exquisite tone and feeling it was odd that they didn’t feature Miles Davis. With his Harmon mute, Miles flat out owned that mofo standard.

We were awash in wonder at the form, discipline, expression and style of the company. Seeing them dance to classic jazz was just an extra treat. The first suite ended with “El Gran Balle de la Reine” by Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

What followed was a brief pas de deux featuring the gorgeous and sensual Crystal Serrano and Dylan Santos. The music by Clyde Otis was performed by Max Richter and featured the emotionally powerful, blues inspired, jazz singer Dinah Washington. The music and dance expressed the irony of love as an antidote to the melancholy of survival on “This Bitter Earth.”

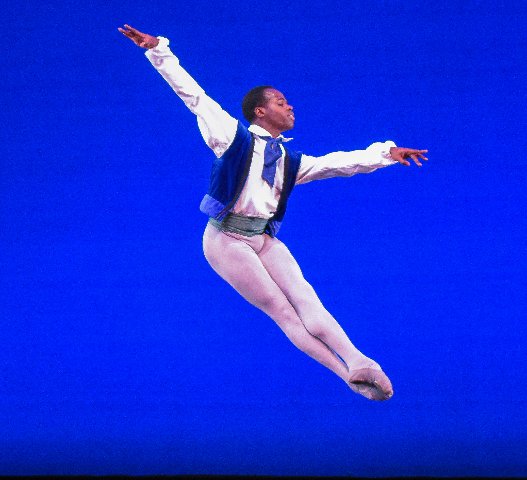

The Balanchine tradition for DTH was aptly conveyed by Valse Fantasie. The long soft green skirts of the women signified the genre of classical ballet. As was noted in the Pillow Talk which preceded the performance the dancers wore, beige flesh-toned rather than traditional pink tights. That also included their shoes. There was a shift of torso color to separate the featured dancer, Ingrid Silver, from the other four women. She partnered with the powerful and expressive Chistopher Charles McDaniel.

They were spectacular dancers and well represented the core mandate of the company that deviates from stereotypes for ballet. One was encouraged to set aside preconceptions about idealized ballet dancers and focus instead on the perfection of their mastery of the art form. It was deviation from the norm that rendered their dance all the more unique, stunning, and spectacular. The Pillow Talk conveyed unique techniques of stepping forward that empowers the women from the passivity and repression of Eurocentric traditions.

The inclusion of Valse Fantasie made an eloquent statement about DTH’s commitment to the Ballanchine approach to traditional ballet. It is that training and discipline that informs and stabilizes their explorations outside the grid.

Proof positive of that mandate is how it functioned in the stunning success of the final piece Balamouk. Set to world music by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa it points to the future for the reformed company under Johnson. The choreographer is the winner of the 2019 Jacob’s Pillow award. Originally commissioned for New York City Center’s Fall for Dance it was enhanced and expanded for presentation at Jacob’s Pillow. That may, in fact, have been problematic.

There was a long pause before the curtain finally parted. There was a haze and to vibrant percussion we encountered a dense cluster of ten dancers. Gradually individuals were emphasized. Goddess like Silva was elevated as the center of the circle seemingly venerated. The circle opened up to a line across the stage separated by gender. The men and women took turns coming forward and being featured.

That in turn broke down to grouping and partnering. This scaled back further until a single woman was center stage in a circle of light. One assumed that to be the end of the dance but they reformed. There was a dramatic shift to a vocalist with strings and percussion. The music and vocals seemed Arabic but Astrid, based on the Pillow Talk, suggested that it was klezmer.

In the final work there were indicators of where dance is progressing. Start with the world beat and add eclectic costumes by Mark Zappone. One bearded individual was dressed They. The dancer expressed male while other signifiers did not. Overall, it was a minor point but nevertheless a marker on the map of change. There was no denying the power, invention and diversity of the choreography. It was exciting dance but that extension seemed not fully integrated.

We left a full evening with a strong sense of struggle, history, progress and change. The firm takeaway is that building on its past fifty years DTH is back on top and here to stay.