Tannhäuser at the Munich State Opera

Awakening to Dissolute Pleasures

By: Susan Hall - Jul 12, 2021

The Munich Opera House may not be the house that Wagner built, but it was an important venue in his career, a place where he conducted, and where his works were premiered. King Ludwig II insisted that the first two episodes of the Ring premiere here. Wagner had hoped to withhold them for his new Festival Theatre at Bayreuth.

Tannhäuser, whose 2017 production is reprised in Munich’s annual festival, was an immediate favorite of Ludwig.

Asher Fisch, known for performing Franz Liszt’s piano reductions of Tannhäuser, among other Wagner operas, conducted. The Bayerische State Opera orchestra has been fine-tuned over the tenure of Kirill Petrenko, who became general music director in 2013. His imprint is clearly felt in the orchestra’s performance, and Fisch took every advantage. As a conductor, Wagner had remarked that instruments sang in their own way, and should be allowed to breathe as the human voice does in delivering music. From the solo harp, the instrument of the title character, to the horns and woodwinds, this early evening performance sang as Wagner thought an orchestra should.

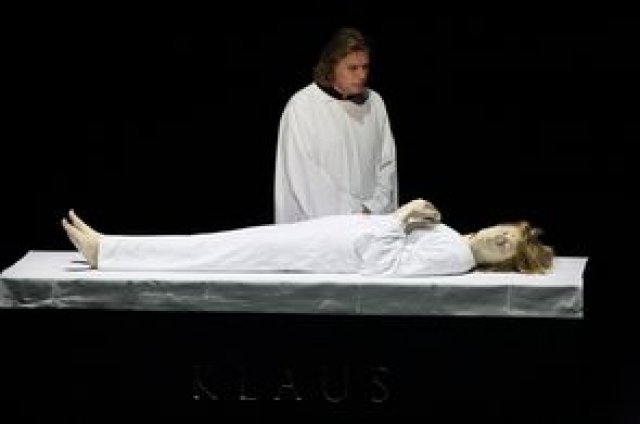

An enfant terrible of the European opera scene, Romeo Castellucci created this production. By and large, it has the advantage of pared down mountings, where the musical drama comes front and forward.

Visuals are created to suggest the constantly erotic tone of life on Venusberg, where Tannhäuser has been residing in dissolute pleasure as the opera opens. Nudity abounds, an added contribution of Castellucci, and subtly entrances.

The overture is decorated with maidens on Venusberg shooting their arrows at the moon, timed to the music’s pulse. This circular central object recurs often on stage. It is Tannhäuser’s face close up, the golden sun of Wartburg, the earthly site of a singing competition overseen by Elizabeth, whose love for Tannhäuser unfortunately transcends the physical. The circle appears for a moment textured and colored like Eve’s apple. You can’t take your eyes off it, but it does not distract from the listening.

This is Castellucci’s talent. With the exception of the sequence of musical bodies, changing figures, each more decayed than the one before, the entire production is subtle. There are silhouetted images, frequent contrasts of black and white with an occasional startling introduction of color like blue flames lapping upward. The arrow is everywhere. as are figures, real and imagined hanging up and down.

Juicy sculptures surround Venus, who crops up from one of them. The glories of the flesh also suggest the decadence. Oscar Wilde mentions Tannhäuser in The Picture of Dorian Grey, the only opera called out in the book about moral degeneration.

Choreographer Cindy Van Acker not only gives us the drawing of the bow in sync, but also bodies in a wave. While what happens at a baseball stadium when a cheering crowd rises and moves around the ballpark has never seemed particularly erotic, Van Acker’s figures are as they swoosh from collapse to arousal to collapse.

In the second act at the Wartburg Hall of Song, translucent curtains sweep the windows ceiling to floor. They are also formed as cones, dancing in the breeze, or perhaps on the breath. Lighting changes with the mood. Elizabeth, the earthly love interest, is swept into these shimmers of material, as are the singers in the competition. The suggestion is delicate, but firmly there. The texture of the drapes and their movement may represent song itself.

Klaus Florian Vogt has made Tannhäuser a signature role. Particularly in the final act, he brought great drama to his performance. He takes Tannhäuser's anguish into his voice and gestures. We see the choice before him, a virginal good woman who loves him, and Venus, architect of his lust and pleasure. Vogt’s voice often penetrates the orchestral line with its bright edge. His reaches for the top notes feel like punctuation marks in the score.

Elena Pankratova as Venus has a voice of unusual lushness. Her vibrato seems natural and gurgles sensually around each note. Her sound is how one imagines sex sounds in music. Pankratova makes Venusberg her own in the very vibrato in her voice.

Lise Davidsen is the soprano to watch today. She is very tall and has the rectangular chest space we often associate with great tenors, the height formed by the long side. The loveliness of her tones conveys Elizabeth's goodness, her innocence and her attraction. Davidsen will reprise Elizabeth in Bayreuth later this summer. She is one of the evening’s stars.

Tannhäuser was the opera from which Liszt found the most material to transcribe. The Overture, which hints at the familiar Pilgrim’s Chorus, the Pilgrim’s Chorus itself, the gala entry of the guests to the Hall of Song, and who can ever forget, the Evening Star, sung with skyward grace by Simon Keenlyside. Familiarity in this case breeds pleasure. It enriches our experience of the work.

All the elements of this production conspired to engage and enthrall. The care so seamlessly evident in all the parts shows us why Munich stages great opera.

Hermann, Landgraf von Thüringen: Georg Zeppenfeld

Tannhäuser: Klaus Florian Vogt

Wolfram von Eschenbach: Simon Keenlyside

Walther von der Vogelweide: Dean Power

Biterolf: Peter Lobert

Heinrich der Schreiber: Ulrich Reß

Reinmar von Zweter: Ralf Lukas

Elisabeth, Nichte des Landgrafen: Anja Harteros

Venus: Elena Pankratova

Ein junger Hirt: Elsa Benoit

Vier Edelknaben: Solist/en des Tölzer Knabenchors

Bayerisches Staatsorchester

Chor der Bayerischen Staatsoper

Musical Director: Kirill Petrenko

Director, sets, costumes, lights: Romeo Castellucci

Choreography: Cindy Van Acker

Videodesign and lighting assistant. : Marco Giusti

Choir director: Sören Eckhoff