Outstanding and varied chamber music at Yellow Barn

with an important revival: Mauricio Kagel's

By: Michael Miller - Jul 13, 2007

Yellow Barn Music School and Festival: First Night AmherstSaturday, July 7 at 8:00 p.m.

Buckley Recital Hall, Amherst College

Stephen Coxe, Clocks and Clouds (after Poème Symphonique, by György Ligeti) World Premiere

Seth Knopp, Jeannette H. Fang, Edward A. Robie, Young-Ah Tak, pianos

Mauricio Kagel, Exotica

Conor Nelson, Tony Flynt, James Michael Deitz, Megumi Stohs, Itamar Ringel, Hamilton Berry

Johann Sebastian Bach, Sonata No. 5 in C Major, BWV 529

Mark Hill, oboe; Jessica Oudin, viola; Kate Bennett Haynes, continuo; Ilya Poletaev, continuo

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, String Quintet in B flat Major, K. 174

Laurel Quartet (Annie Rabbat, violin; Yinq Xue, violin; Sarah Darling, viola; Song-Ie Do, cello) and Roger Tapping, viola

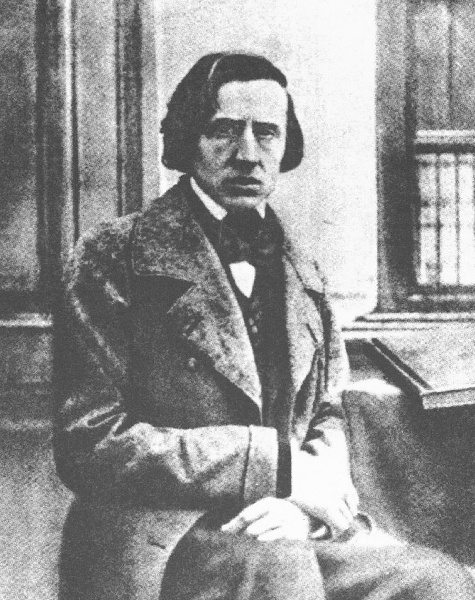

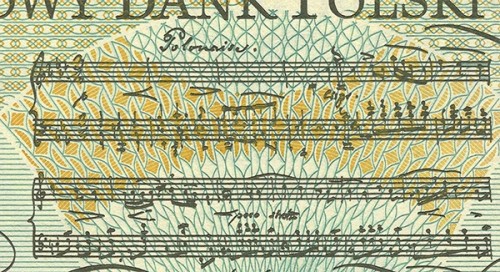

Frederic Chopin, Nocturnes (Op. 55, Nos. 1-2; Op. 27, No. 2)

Peter Frankl, piano

Yellow Barn is an impressively active music school and festival with classes and public concerts at two venues: Putney, Vermont and Amherst, Massachusetts. Their summer season began on Friday July 6 in their own Yellow Barn Concert Hall in Putney and will continue until August 4, when two concerts, one at noon in Amherst and the other at 8 pm in Putney will conclude the season. Under the directorship of Seth Knopp, some of the most distinguished names in chamber music gather with a group of some 40 musicians in the early stages of their professional careers, most of whom are currently enrolled in, or have recently graduated from, conservatory or graduate school. I was told that many come back for a second or third year or more. There are master classes open to the public, and the young musicians participate in the formal concerts along with faculty, as at Marlboro.

This expansive and many-layered endeavor began informally in 1969, when cellist David Wells, then chair of the chamber music department at the Manhattan School of Music, established a country retreat in Putney and invited his students to join him there for a musical summer. As it has evolved, the sophistication and professionalism of Yellow Barn is attractively balanced by intimacy and friendliness. As apprentices and faculty congregate with the audience during the break and afterwards at the reception, it is easy enough to pass on a personal comment on the music or the performance or to engage in a more extensive conversation. A typical Yellow Barn program will combine classical, romantic, or modern classics with contemporary music, making for a relaxed and eclectic experience of chamber music. The young musicians, from what I heard and saw at Saturday's concert and the preceding master class with violist Kim Kashkashian, tend to be musically mature, with highly developed personalities—a trait which gives a Yellow Barn performance a character all its own, quite different from a Marlboro or a Bard performance.

Saturday the energetic and nuanced performance of Mozart's early masterpiece the String Quintet in B flat Major, K. 174 by the Laurel Quartet, joined by Yellow Barn faculty member, Roger Tapping, viola, a former member of the Allegri and Takács Quartets. While Tapping's strong, clearly defined playing grounded and energized the performance, the younger participants showed considerable individuality in phrasing. Nonetheless they came together most satisfyingly as a unified ensemble. In order to understand the degree and variety of experience of the players in this honors ensemble at the New England Conservatory you would have to consult the biographies offered in the Yellow Barn program or on their Web site. The younger musicians appear in general to be at the point of emerging from their student days and establishing themselves as mature musicians, if not well beyond that.

The same came across in the performance of the evening's world premiere, Stephen Coxe's Clocks and Clouds, after Poème Symphonique, by György Ligeti (1962) for 100 wind-up metronomes. In his hommage Coxe abandoned Ligeti's original scoring for two pianos, four hands. The shifting sonorities and rhythms, which developed into rich sonorities from spare, isolated tones at the beginning, proved absorbing and convincing, while the humanity of the players gainsaid somewhat the composer's desire "to combine extremes of expression: patterned, mechanistic, and impersonal procedures, succeeded by sorrow."

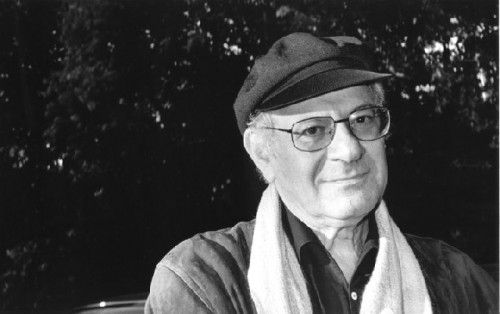

If this new piece is rooted in Ligeti's avant-garde gesture of the early 1960's, Mauricio Kagel's Exotica, commissioned for the 1972 Munich Olympics, brings us into the center of new music at the end of that decade, a kind of music-making which has been forgotten to some extent over the generation which separates us from it today. However, before discussing a piece which is so intimately related to performance—and I mean performance not in the sense of Yo-Yo Ma or Leonard Bernstein, but in the sense of Joseph Beuys and John Cage—I should say something about the occasion and the environment.

Yellow Barn's Amherst concerts take place in Buckley Recital Hall in the Arms Music Center at Amherst College, a typical academic structure of brick and concrete finished in 1968. The building exudes function over style. Buckley Hall, which seats 500, is fairly basic but nicely proportioned, and the acoustics show some problems, but are good enough on the whole. (For us Williamstown residents, a comparison painfully brings home the inadequacies of Williams' Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall.) The audience consisted largely of faculty members from the five colleges, many of whom are old enough to heard the piece when it was new. Back then, as a student of Christian Wolff—in Euripides, not music—I was no stranger to this kind of performance myself. If there were smiles on some faces (Some even laughed outright.), there was an element of recognition in them, even of nostalgia. Our ironic smiles were directed as much at ourselves as at the music, which was of the sort which in 1972 would have either kept us in a state of tolerant and pious receptivity or sent us packing. It was clear enough, as we looked at the six performers sitting cross-legged on an oriental rug, surrounded by exotic musical instruments, that this was music of a past generation, and a great deal has come between, although it is interesting to note that the first American performance of Exotica did not occur until 1988 at Cal Arts, as Susan Halpern points out in her program note, in a building probably not unlike the Arms Music Center (Why do these performances have a way of happening mostly on campuses?), bridging the thirty-five year gap in time. The exotic—extra-European, to use Kagel's term—instruments had the dull look of objects which had been long in storage, "gathering dust" in a specialized collection.

The title Exotica itself underscores the Eurocentricity of this music. Kagel stated that the primary purpose of the "extra-European" instruments is separate the musicians from the instruments on which they were trained. After all, highly developed proficiency on a single instrument is fundamental to western music. As Kagel stated: "it would cast such doubt on the professional competence of the participants that every one of them would probably invent music out of sheer terror and panic, but also, perhaps out of irony and joy."

Kagel indicated that the score be executed by six participants and a conductor. Each of the players executes a vocal part simultaneously with an instrumental part, favoring the vocal in case of conflict. The performers "improvise their own choice of words or word-like combinations," suggesting extra-European speech, taking care to avoid any suggestion of banal imitation or the comic. "Exotica is made up of five parts...whose order is free." They can even overlap. In this performance one of the players, percussionist James Michael Deitz, doubled as leader in the place of a conductor. The result was fascinating and impressive, above all for the sensitive interaction among the musicians, not only in the beautifully executed rhythmic interchanges, but in the rather potent chemistry developed through eye-contact and responsive singing. While the comic moments proscribed by the composer could not be avoided (Every work of art goes through some phase of datedness.), it was clear that Exotica is still—or, better, again—a vital piece today.

I should not neglect to mention Peter Frankl's beautifully balanced performances—both in tone and in tempo—of three Chopin Nocturnes, music which once enjoyed its own aura of exoticism, and no weaker for having outgrown it. I have admired Mr. Frankl's sensitive but straightforard pianism for many years, and this was no disappointment.

Of course today our approach to the "extra-European" is quite different. One could say that our borders, if not our horizons, have expanded. So many colleges like Amherst, Williams, or Bennington have well-established world music programs, not to mention urban concert halls. A lot of energy is focused on studying musical traditions around the world, restoring as much as possible of lost traditions through research and mastering to perfection many of those same exotic instruments we saw on the stage at Buckley. They are studied with the same obsessive perfectionism as Stradivarius violins. This expansion has its historical complement in the early music movement. Just around the time Kagel was making the first recording of Exotica, Jordi Savall and Monserrat Figueras came together in Basel and founded Hesperion XX, today among the leaders of the movement, and certainly one of the most popular. Their Thursday evening concert at Tanglewood of music of the Sephardic diaspora illustrates my points both about the exotic and about history. I hope you will read my forthcoming review as a pendant to this one.

Meanwhile, as a final thought about Exotica, I should mention that Kagel dedicated the piece "to the sixth sense." Again, what could be more European? Many of the cultures which produced those exotic instruments had no need for the concept.

Web: http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

e-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com