Villa America at Williamstown Theatre Festival

The Lost Generation's Flophouse

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 15, 2007

Villa America

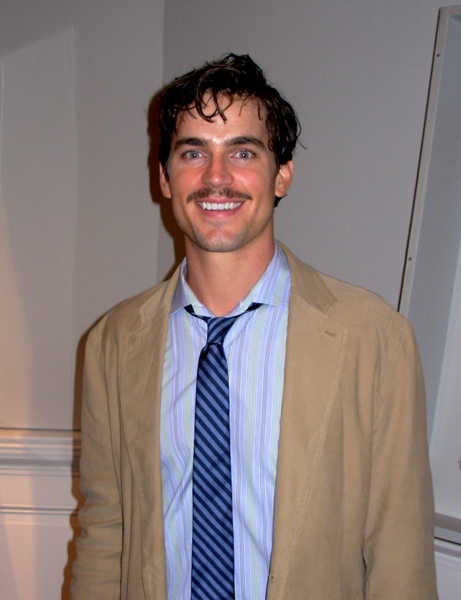

Written and directed by Crispin Whittell. Sets Mimi Lien. Costumes, Emily Pepper. Lights Thom Weaver. Sound, Nick Borisjuk. Production Stage Manager, Gregory T. Livoti. Production Manager, Michael Wade. Casting, Laura Schutzel, Tara Rubin Casting. Cast: Mrs. Murphy/ Henriette/ Adeline Wiborg, Charlotte Booker, F. Scott Fitzgerald/ Nate Corddry, Honoria Murphy Donnelly/ Sara Murphy/ Jennifer Mudge, Ernest Hemingway/ Matthew Bomer, Pablo Picasso/ David Deblinger. The Williamstown Theatre Festival, July 11-22.

The life of Gerald and Sara Murphy, the social and moral compass of the Lost Generation and subject of the major exhibition "Making It New" at the Williams College Art Museum, inspired a great literary masterpiece "Tender Is the Night" by their friend, F. Scott Fitzgerald, an award winning biography by Amanda Vaill "They Were All So Young," and a memorable New Yorker essay expanded into a short book by their late in life neighbor, Calvin Tomkins. So why not play spin the bottle one more time? Accordingly, a young British playwright, Crispin Whittell, who was interviewed for BFA about this project, was commissioned to write a play "Villa America" which is on stage at the Williamstown Theatre Festival through July 22.

Given the richness and complexity of the Murphys, he a brilliant artist in a career cut far too short, and she one of the great beauties of her day, surrounded by the best and brightest stars of the Lost Generation, they seemed a natural for a compelling drama. All the elements were there in a great and tragic love story. The challenge was to sort through such a wealth of material and to find a form on which to base an action surrounding these stunning and now legendary figures. In hindsight, we are talking about some of the greatest artists and celebrities of their era.

Of their many fabulous friends Whittell confined himself to three men, all in troubled marriages, who loved and lusted after Sara. She must surely have been an amazingly, sensual, charismatic and vampish woman to attract the amorous attentions of F. Scott Fitzgerald, married to the mentally deteriorating Zelda, the macho Ernest Hemingway who lusted after anything that moved, then falling out of love with Hadley, and Pablo Picasso struggling to become disentangled from the Russian dancer, Olga, from whom he eventually separated but never divorced.

As Whittell explained to me the women, other than Sara and a curious choice, a French maid badly portrayed with an atrocious accent by Charlotte Booker who doubles in the opening scene as the older Mrs. Murphy, he excluded the famous wives from the drama, although they are much discussed particularly the antics of Zelda, as he felt that they would offset the balance. But, as one reviewer stated, and I tend to agree, the best characters (the wives, particularly the riveting and manic Zelda) is never seen although her presence pervades the play as a subplot and contrast to the witty and flirty Sara.

And what of Gerald who in this play is reduced to the cuckolded husband who was a gracious host to a circle of men determined to bed his wife? The Whittell drama makes no effort to flesh him out and reveal his remarkable skills as a wit and facilitator, to say nothing of his accomplishments as an artist. Instead he is there to play along with the pranks and torments of the clever and dominating Hemingway, most compellingly played by Matthew Bomer. Gerald, portrayed with bisexual ambivalence in a misdirected performance by Karl Kenzler, is lured into the buffoonish posture of playing the soon to be dispatched bull to Hemingway's flamboyant matador. Ernest informs us that he thrives on war, tobacco, booze and fornication. He seeks out death, combat and blood sports as sources for writing. He tells Sara that Scribner is about to publish "The Sun Also Rises."

To keep his blood thirsty sensibility alive and kicking he sports a revolver and, as the action ensues, it seems that he had drilled a Bluefin through the eye, which he drags on stage during his first appearance, as well as the family pet, mistaken for a varmit. But Scott, played way off key by Nate Corddry, is locked into a macho competition with Ernest. They are rivals both as authors and suitors for the attention of Sara. Ernest is just a skirt chaser, accused by Scott as a closet homosexual, while Fitzgerald appears to truly love Sara. Scott complains to Ernest that he doesn't have the physical equipment to satisfy Zelda who is described as a nympho. Ernest offers to take a look at his member but has to see it at the proper angle, from his knees head on. He promises to keep the examination secret but immediately and with derision blurts out his findings to Sara. There is much in this play about just who is in or out of the closet. Significantly, there are two changing rooms or closets in the set.

The rivalry between the authors culminates with insults and fisticuffs. Indeed the literary clash and conflict of the two great American writers of the Lost Generation delivers the high point of rather tepid action. There is literaryy insight when Scott comments that Ernest writes about death, a subject about which Fitzgerald knows nothing, while Scott prefers to write about life and things he knows. He is riding on the success of the publication of "The Great Gatsby." He hasn't done much since then but drink himself into a stupor and put up with his progressively more deranged wife.

Like Gerald, Whittell conveys Scott as a fool but in a different way. Again we find little of his redeeming wit and genius. In real life Scott devolved into a bad drunk and a bore. He was one of the truly tragic, tormented creators of his time. Although he was a successful and famous writer in the 20s it was mostly down hill in the Depression years of the 30s when his Jazz Age stories were out of fashion. Returning to America he hit rock bottom in Hollywood as a hack working on scripts that never got produced. He was loved and nurtured through those grim times by a gossip columnist with a heart of gold, Shelia Graham. Significantly, while he often behaved badly, the Murphys never abandoned him and supported his daughter Scottie through college. Fitzgerald was wasted and washed up when he died at forty four in 1940. But he committed Irish suicide rather than blow his brains out like the macho Hemingway who liked to kill things including himself.

And what of Sara who is portrayed by Jennifer Mudge? The few kind words in the mostly scathing reviews of this play have been for her performance. These critics are seeing this purely as theatre. Prior to this performance few of the critics appear to have known anything about the Murphys. One writer suggested that one Google the Murphys and we assume that he did. But it takes more than Wikipedia to fully appreciate her importance and complexity. The Sara in my heart and mind was not conveyed by Booker. She may have been interesting to some critics and perhaps the audience, but trust me, there is no way she was anything like the real Sara Murphy.

Part of the issue was a conscious decision by Whittell which he discussed with me both before and after opening night that he did not want to give the play what he called a "Merchant and Ivory" treatment. This is to say a costumed period piece. For precisely that reason Sara and the men that surround her perform like contemporary players who have been plopped down by some time machine onto the beach of Cap d' Antibes. The setting and action are as arid as the beach on which it is staged with a rather clever set by Mimi Lien and the effective lighting of Thom Weaver. There isn't much in the way of costumes other than beach attire. Ernest is incongruous in cutoff shorts. That style is more 60s than 20s. Scott is made to appear absurd in some ersatz Indian getup from a drunken costume ball the night before and later appears on the beach to go swimming in knickers and knee socks.

The time line of the play in four scenes begins and ends, 1968, and 1915, when Gerald proposed on the beach at East Hampton. The play opens in a night scene in which Sara, whose Gerald has been dead for four years is visited by the ghost of Scott on the anniversary of her husband's death. Both she and we are confused by that. Where there should be some charm and whimsy, an air of nostalgia, the performance by Booker is awkward and uncompelling, while Corddry's Scott is just uncomfortable and eager to return to Hades.

The middle scenes are set on the tiny beach in Antibes in 1926 and again in 1923. Here we first meet Scott and Ernest and then most absurdly Pablo shows up, abominably portrayed with an atrociously phony accent by David Deblinger. While there is a physical resemblance to the thick figured young Picasso Whittell has him delivering lines while plunked down on the beach. It is an absurdly awful scene with hilariously bad acting. The dialogue is about artists convincing women to take their clothes off. Which Pablo, even from the most preposterous position, talks her into. For just a few moments we are exposed to the voluptuous curves of Mudge. It was sporting of her to consent to this but hardly made an impact on a play which by then was as thoroughly Lost as the Generation it was intended to convey.

Lost, perhaps, but hopefully not abandoned. There is still a play in all this if Whittell undertakes the appropriate revisions. The disaster of this production is that it was directed by the author. I feel that he is a more gifted writer than director. This play needed another opinion to make the right suggestions for revisions. Whittell clearly lacked the objectivity to properly edit his own work. With an extreme makeover it may not be too late to salvage what is left of the run of this commissioned piece. Unfortunately, as it stands this casts a dark cloud over a well intended effort for the theatre and museum to collaborate.

It is just a thought, and perhaps none of my business, but another idea might have been for WTF to revive the 1923 collaboration of Gerald Murphy's sets and costumes with the music of his great friend from Yale, Cole Porter, and their ballet "Within the Quota" for Rolf de Mare's Ballet Suedois. That might have given us a better and more authentic sense of the genius of Gerald Murphy. Oh well.