Estonia

Tallinn, the capital city

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 20, 2015

On our way to Tallinn, the northernmost of the Baltic capitals and the largest, we stopped in Parnu, the country’s third largest city and its premier seaside resort along a long coastline of 1000 miles. On the beach were families with children playing in the shallow waters. Taking our shoes off, some of us also tested the water, which seemed warmer than anywhere else. The shimmering waters drew people like a magnet, underscoring the popularity of this resort.

Of Estonia’s population of 1.3 million, 420,000 live in Tallinn. We entered the city through new Tallinn via a wide artery lined with modern buildings, all constructed since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Our hotel, the Radisson Blu Sky, was a contemporary 24-story high-rise with a roof-terrace and spacious guest rooms. Nearby, the Swiss Hotel was the newest of the high-rise buildings, all of which had replaced single residential homes with gardens bombed during WWII. Following a delicious dinner of tomato and mozzarella salad, whitefish with potatoes and broccoli, and cheese cake for dessert, I returned to my room on the 10thfloor at dusk, just as the sky silhouetted the spires of the medieval Old Town.

Joined by a local guide in the morning, we drove out to the grounds of the Tallinn Song Festival, the heart of the Singing Revolution at the end of the 1980 s, when 100,000 people gathered here to sing national songs against the Soviet regime. On the spacious grounds stands a statue of composer, choir director and festival leader Gustav Ernesaks, known as the Father of Song. There is also a huge concert shell for musicians participating in the festival, which takes place every five years. Annually on “white nights,” the grounds also host a beer festival, where people listen to pop, folk, and country music in different tents while enjoying beer, Estonia’s national drink.

Afterwards, we descended to the Pirita district by the seaside. The district is named after a 15th-century monastery, whose ruins are near the coast, alongside yachting clubs, which hosted the 1980 Olympic sailing regatta. Tallinn sits on the southern shore of the Bay of Finland, 80 km from Helsinki across the bay and 250 km from Stockholm; it has a busy harbor with many cruise ships. Facing the harbor is a monument built by the Russians in 1902 and commemorating a Russian naval ship, the Rusalka, which sank in the gulf along with the soldiers on board.

Proceeding to tour the Old Town, we started at Toompea, or the Upper Town, where the city began to form in the tenth century on the steep spur of an ancient lime plateau at a bend in the Gulf of Tallinn. The natural properties of this plateau, made of thick layers of flagstone, allowed the ancient Estonians to build a defensive fortification here. Some of the medieval structures have survived, but most have been replaced by new ones.

Due to Tallinn’s favorable geographic location, the city developed through commerce by Hanseatic merchants. For administrative purposes, the city was split into two independent parts: Toompea, or the Upper Town, and the Lower Town. This division survived in general terms until the late 19th century, when stone buildings were built in both towns for fear of fire.

One of the most recent buildings of Toompea is the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, built in 1900 in Byzantine style, when the country was part of the Russian Empire. A sharp contrast to the surrounding Gothic structures, the Orthodox Cathedral, with its richly decorated interior, has five onion domes topped with gilded iron crosses.

Unfortunately, the narrow streets were packed with tourists, who had just arrived on a cruise ship. It was a challenge to photograph the impressive roofs, towers, and spires of the Old Town from the viewing platforms of the Upper Town. Patience prevailed and I was able to enjoy the picture-book red roofs, framed by the greenery of gardens stretching all the way to the sea.

The Lower Town features a lively Town Hall Square, complete with outdoor mimes entertaining passers-by, against a backdrop of houses with steep gables. Well-preserved 14th- and 15th-century buildings line cobbled streets, many of which house cafes, galleries, and craft shops. Tombstones of the Wacke family, dating from the late 14th century and brought from St. Catherine’s Church during its restoration, have been mounted on the wall along Kohtu street, creating an unusual display. During free time in the afternoon, I continued perusing craft shops and walked back to the hotel in time for a scheduled “smart talk” on Estonian Independence.

Ameli, a professor of international relations, described Estonian Independence as “taking misery and spreading it evenly.” The country went from a planned economy to a market economy overnight. A private sector began to form; young people became parliamentarians and mayors. In 2009, unemployment hit 24% and GDP fell by 14%. Wages were cut and taxes raised from 18% to 20%. The euro became the currency in 2011. There is little organized labor; trade unions are weak. The main export is timber; 50% of the country is forest; 3½% of the population is farmers, down from 80%. The education system is good, and there are seven universities in the country, the oldest dating from 1632. The people are very sophisticated in the use of electronics; Skype was invented by two Estonians. However, educated people are leaving because of low wages. 25% of the population is native Russian speakers. Tallinn had 3.6 million visitors in 2014. The speaker ended by stating: “People are optimistic because of freedom; everything is 24 years old or younger in Estonia.”

The next morning’s excursion to the Kadriorg region exemplified Estonia’s transition to today’s nationalist youthful spirit. We took a local tram out to Kadriorg, whose history is closely related to the Russian Tsar Peter the Great. Walking through the forested Kadriorg Park, we crossed paths dotted with statues and ponds surrounded by manicured gardens and fountains. Among the statues, one on a pedestal is of F.R. Kreutzwald (1803-1882), considered the father of national literature, as well as a leader of the national awakening.

Kadriorg Palace, built by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia in 1718, was named in honor of his wife Catherine I (Kadriorg means “Catherine’s Valley” in Estonian).The baroque palace, modeled after Versailles, is surrounded by a garden with fountains, statuary, hedges, and flower beds. The summer residence of Russian emperors until 1917, it was renovated in 2000, and opened as the Kadriorg Art Museum, displaying Estonia’s collection of Old Russian and Western European art.

On the grounds, symmetrically aligned with the palace is the official residence of the current President of the Republic of Estonia. The neo-baroque structure was built in 1938 as the Office of the Republic near the then official residence in the palace. The Presidential Palace, which housed the President of the Supreme Soviet during the occupation, now proudly flies the Estonian flag — three bands of blue, black, and white, respectively symbolizing the sky and sea, earth, and hope.

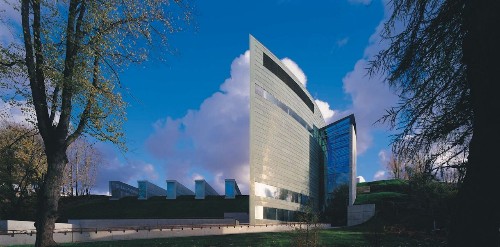

On the edge of Kadriorg Park is the KUMU, the modern Art Museum, which displays Estonian art and sculpture from the 18th century to the present, including Soviet-era works. The impressive building, which opened to the public in 2006, is the result of an international architecture competition. The winning design by a young Finnish architect, Pekka Vapaavuori, has seven stories, two of which are underground. Having received the European Museum of the Year Award in 2008, the KUMU — a shortened version of the Estonian word kunstimuuseum (art museum) — bears witness to Estonia’s determination to build its future. (Look for a separate article on the KUMU in BFA’s fine art section soon.)

Taking the tram back, we returned to our hotel. However, Vita suggested a different path away from the tourist footprint, in order to see the city wall from a different perspective. We walked on quiet narrow streets along the wall until we came to an opening, which provided a view of four city wall towers aligned. A nearby installation called the “Olympic Game of Flowers” caught our attention with its international flags at ground level. This was a climbing competition among flowering vines from different countries; it took place on a race track created by wooden rods, indicating which vine was ahead to be the winner in 2015. This ecological installation also showed the Estonians’ preference for individual competition, as they excel in sports such as sailing, cross-country skiing, and weight-lifting.

Upon returning to the city, we encountered a group of people demonstrating across the street from the Russian Embassy. Waving Estonian and Swedish flags, they held up placards telling Russia to get out of Ukraine. Returning to the hotel, I found that the roof terrace was closed for a private function, which turned out to be a NATO meeting in town. All three Baltic countries feel comforted by having the US navy in their seas. People live with the memories of their hard-earned independence, which they sealed by forming a 600-mile human chain stretching from Vilnius to Riga to Tallinn. The Singing Revolution is in recent memory; the song they sang in three different languages is still on people’s lips: “We’ve been sleeping too long; it is time to wake up.” They are determined not to fall asleep again.

The following morning we left for St. Petersburg, Russia, stopping first by a 7000-year-old Bronze Age burial ground found by the roadside. The graveyard has been relocated and the excavated objects have been taken to a museum. My parting image of beautiful Estonia was the circular arrangement of limestone grave markings by an expansive, lush green meadow.