Breaking the Code at Barrington Stage Company

Enigma of Alan Turing Brilliantly Portrayed by Mark. H. Dold

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 21, 2014

Breaking the Code

By Hugh Whitemore

Directed by Joe Calarco

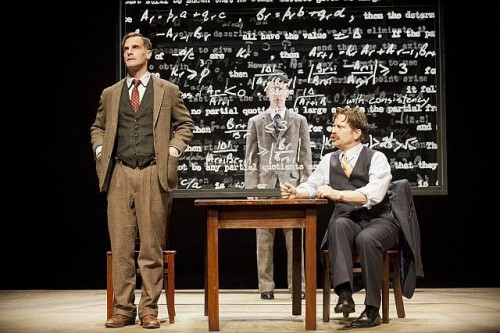

Scenic design, Brian Prather; Costumes, Jennifer Caprio; Lighting, Chris Lee; Original music and sound Lindsay Jones; Wigs, Rob Greene and J. Hared Janas; Voice and dialect coach, Wendy Waterman; Director of production, Jeff Roudabush

Cast: Mark H. Dold (Alan Turing), Deborah Hedwall (Sara Turing), Mike Donovan (Christopher Morcom/ Nikos), Philip Kerry (Dilwyn Knox), Annie Meisels (Pat Green), Jefferson Farber (Mick Ross), John Leonard Thompson (John Smith)

Boyd-Quinson Mainstage

Barrington Stage Company

July 17 to August 2, 2014

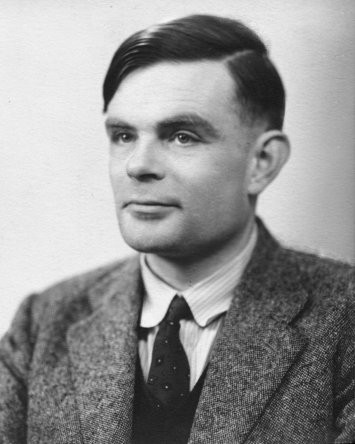

Alan Mathison Turing (23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) is among the most important individuals of the 20th century whom most people have never heard of.

From the inception of World War Two he was among 10,000 individuals, some 80% of whom were women, who worked round the clock at top secret Bletchley Park to decipher codes generated by Germany’s complex Enigma machine. The device had five rotors which were changed daily with combinations reaching endless variations.

He was a British mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, computer scientist, mathematical biologist, marathon and ultra distance runner. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalization of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which predated a general purpose computer. He is credited as the "Father of Theoretical Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence.”

In 1999, Time Magazine named Turing among the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century. In 2002, Turing was ranked twenty-first on the BBC nationwide poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. In 2006 he was listed as one of twenty people featured in a book about famous historical figures with traits of Asperger syndrome.

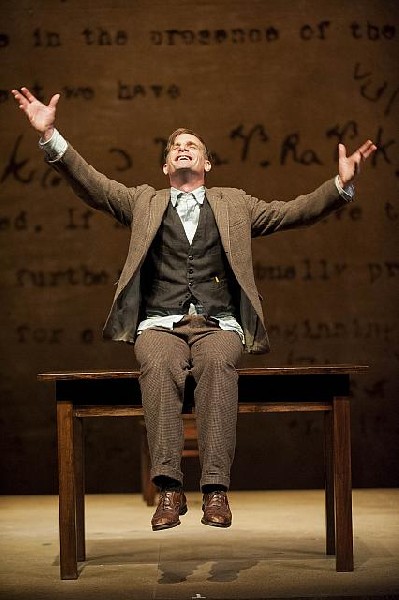

From stuttering speech to quirky body movements every fiber of Mark H. Dold, in a career defining performance, conveys the genius, torment and eccentricity of Turing.

On every level from acting to stagecraft Breaking the Code by Hugh Whitemore, directed by Joe Calarco, is among the finest and most compelling productions we have seen by Barrington Stage Company.

The season opened with Calarco directing the well received, upbeat musical Kiss Me Kate. Barrington has followed with the day and night difference of a complex, multi-valent, riveting staging of a nail biting and infuriating drama. Calarco is in residence this summer and we eagerly await his third Barrington play.

The evening opens with the audience contemplating a square platform in the middle of the stage. On it is a simple table with a light (designed by Chris Lee) illuminating a single red apple. Augmenting this austerity, designed by Brian Prather, are panels above and flanking the platform which are occasionally illuminated with mathematical formulas.

The seven person cast is seated on the periphery of the platform. At times they will join the action on center stage or just sit and listen. During some segments they turn their backs as though shunning Turing. Other than his mother (Deborah Hedwall) and a single female colleague (Annie Meisels) he was abandoned after confessing to a homosexual relationship with an out of work boy who had sex for money. Turing was prosecuted, persecuted and eventually driven to an alleged suicide.

Known to eat a daily apple the final one may have been dipped in cyanide. There was never a forensic test of the apple during an autopsy that assumed suicide. His mother and others believe he may have carelessly inhaled rather than imbibed the toxic fumes. Under crude conditions, denied a proper laboratory, he was performing chemical experiments in his kitchen.

Like so many aspects of his life even death remains an enigma. Since Turing was essential to the development of computers and artificial intelligence it has been alleged that the Apple logo is a tribute to him. Steve Jobs was intrigued by that possibility but denied that it occurred to him.

In two acts during a long and complex evening Whitemore undertakes the multi tasking of presenting the originality and vulnerability of the man. The play includes quick sketches of his formidable accomplishments in cracking the Enigma code, as well as efforts in science, mathematics and technology. The play functions simultaneously as riveting drama and science lecture.

For me it was successful on all of its levels and agendas from human and personal to ambitiously philosophical. Consider the tantalizing asides about Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) who influenced Turning’s theories.

There are also snippets of Turning's eccentricity. We learn that out of fear that it would be lost or stolen at Bletchley Turing chained his tea mug to a pipe. He was not noted for social skills. Other than work related colleagues, or the occasional furtive sex partner, he really had no friends.

All those who worked at Bletchley Park signed off on Britain’s Official Secrets Act. They were forbidden to discuss their work with colleagues, spouses, relatives or friends. It would be decades before their findings and files were declassified. There was no public recognition of their part in the war effort. Churchill acknowledged that Turing played an essential role in shortening if not ending the war.

As a leader of Bletchley, who traveled to the U.S. and returned with information on American research, what Turing knew was particularly sensitive.

There was a common thread of homosexuality among the Cambridge Five a ring of spies. During the war and into the 1950s they passed secrets to the Soviet Union. Four members of the ring have been identified: Kim Philby, Donald Duart Maclean, Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt an art historian and curator to the collection of Queen Elizabeth.

During the post war Red Scare McCarthyism and homophobia prevailed in America. Sexual vulnerability was routinely exploited in the spy game. In a climate where homosexuality was a crime knowledge of it was used for blackmail. We have seen a lot of that in the brilliant TV series The Americans.

When Turning was robbed by an associate of his paid lover he reported the theft. During the investigation, when his story didn’t ring true, unsolicited he blurted out details of an affair with a teenager. He was brought down by a self inflicted blunder.

It was then a crime in Great Britain and he was prosecuted for Gross Indecency. Found guilty by his own admission he opted for probation rather than prison time. That entailed neutering estrogen treatments.

The brilliant Barrington production manages to keep us enthralled while all these treads and plot points are advanced. This is entirely the accomplishment of Dold who never drops a stitch in this intricate humanist tapestry.

Because of the density and complexity of the drama it is intuitive for the audience and critics to focus on some aspect of the play. It is possible to take away many individual impressions of the experience. Perhaps it is a play to be seen several times, hopefully in different productions, in order fully to be absorbed.

Some time ago, for example, we saw the Derek Jacobi performance of the Turing story on PBS. He performed the play in London and New York. What we saw on TV was adapted from this play. Prior to that I knew nothing of Turing or Bletchley Park. Over the past couple of seasons we have much enjoyed the PBS series The Bletchley Circle. It focused on several women who under vows of secrecy went back to nondescript private lives. They regroup to apply their Bletchley skills to solving crimes.

Dold’s character provides glimpses of the unique qualities of Bletchley. It recruited a motley array of individuals from scientists and mathematicians to chess and crossword puzzle champions. In essence anyone capable of thinking outside the box. He complains of the post war academic years at Manchester when he is again confined to a field in his case mathematics.

In the war effort at Bletchley they were willing to try anything. And, apparently, it worked.

It is intriguing to hear how they attacked the problem. At the beginning of each coded message there was boilerplate of date, time and the name of the operator. Cracking that allowed for more complex unscrambling. Turing focused on mistakes and lapses in the transmissions. These provided mathematically predictable intervals that led to the development of what we today call algorithms which can be programmed.

He developed a device using electronics which greatly accelerated the speed of such calculations which daily produced 158 quintillion possible solutions. It allowed for identifying the daily settings of the five rotars.

The approach was essentially similar to how hieroglyphics were decoded using the Rosetta Stone. The object included the identical inscription in hieroglyphics, demotic script and ancient Greek. Once the cartouche was identified with the name of the pharaoh in the two known languages the cryptologists worked out from there.

With no Rosetta Stone cracking the Enigma Code entailed the intensive labor of thousands of individuals. Turing ran the all important Hut 8 but hardly broke the code and won the war by himself. That’s a charming bit of hyperbole. Without question, however, he was the foremost player.

Secrecy was essential as the Germans never knew of the progress of the Bletchley group. They might have made adjustments of equipment and operation making it impossible to further crack the code.

During the early stages of the war German U Boats hunting in wolf packs were decimating the shipping lanes. Once the code was cracked the submarines, as seen in the film Das Boot (1981), this threat was virtually eliminated. Through intercepted transmissions the Allies pinpointed and destroyed the U Boats.

In all of its phenomenal complexity everything comes together in this production. But you have to remain alert to nuances of information.

Start with a strong physical resemblance between Dold and Turing. Then add to that the shabby costume designed by Jennifer Caprio. He had a complete disregard for personal appearance and hygiene. There are wonderfully nervous gestures, like manic brushing back of his hair, and lurching movements that define his character. If indeed Turing had symptoms of Asperger's Syndrome he had an aversion to physical contact.

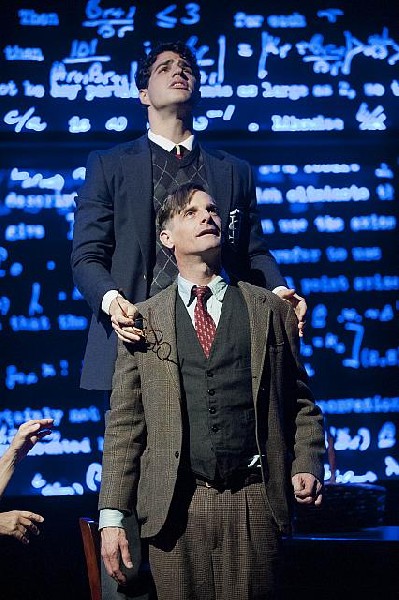

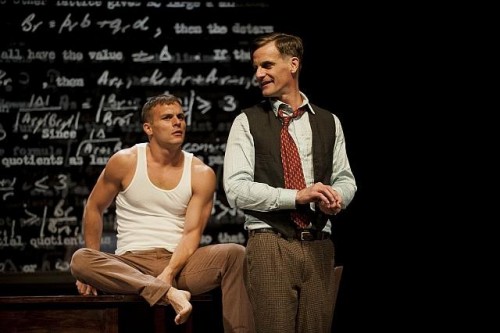

The body language is distinctly different when Dold recoils from his ditzy mother (Deborah Hedwall) or carefully fends off the affection of a colleague, Pat Green (Annie Meisels), who loves him. Compared to the distance he seeks from female affection we are intrigued by his lust for the young and doltish Ron Miller (Jefferson Farber). Their one sided liaison is entirely carnal. That compares to the romantic love he exuded for his schoolboy love Christopher Morcom, who died young, and then the thrashing about in Greece with a nude Adonis, Nikos. Both boys are played strikingly by Mike Donovan.

There is a range of other characters from colleagues to cops who flesh out the narrative.

The scene with Pat Green is particularly poignant. They meet for a picnic to catch up after an interval of years. She is now a married mother. He speculates on how it might have been different had he married her and remained closeted. She reveals that this is precisely what a superior had done. He is shocked by the revelation.

It was the norm to have gay lovers in college then pretend to be straight with a compliant wife who was often onto the game. Ms Green, who loved him, was perfectly agreeable to such an arrangement and this is conveyed with tenderness and credible conviction.

Referring to the year long estrogen treatments he is self conscious about developing breasts. He tells her that he is concerned that he may have to wear a bra. In these scenes Dold clutches his shabby coat as if to conceal them.

This aspect of the play infuriates me. The treatment and “cures” for gays were barbaric. One cringes to recall the trial of Oscar Wilde. It was a theme in the Williamstown production of Far from Heaven and In the Wilderness this season. Just last night in the Showtime series Masters of Sex a character attempts suicide when electric shock therapy fails to cure him.

There is a lot going on in Barrington’s Breaking the Code. It is the kind of experience that gets inside you and won’t quit. The play advanced our understanding of history, science and technology but left me enraged. Caveat emptor.