Report on Southeastern Turkey: Part Three

Midyat, Hasankeyf, Diyarbakir

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 22, 2008

Midyat

Traveling 24 kilometers east of Mardin through a terraced green landscape with grazing sheep and mud brick houses, we reached Midyat at 1000 meters above sea level. In the same administrative district as Mardin, Midyat is the holy center of the region's large Syrian population, who fast seventy nine days of the year. From 9th century BC Assyrian tablets, Midyat's original name is understood to have been Matiate, meaning "cave city" in Assyrian. Early inhabitants lived here with their animals in caves.

There are two parts to the city, the old and the new. The old districts have retained their historic character with houses resembling the stone houses of Mardin. Columns and arches, and the frames of gates and windows, are all adorned with different motifs. In 2001 the town was officially declared a historic site, with 199 registered structures of historical value, including churches and mosques. Stone work continues in new constructions with thick walls and windows that do not face the windows of other houses.

Midyat is famous for its telkari (filigree) and silver crafts; it is accepted as the birthplace of filigree work. This unique craft is produced by embossing carved wood with designs in silver or gold wire. Telkari masters produce jewelry and boxes, as well as delicate bags and belts with a variety of motifs. The main street is lined with small silver shops, where we easily spent an hour going from one to the next. I bought a silver filigree bracelet with a flower motif and a leaf-shaped ring at modest prices, as each was sold by weight.

Descending from the clay soil of old Midyat, we reached a green valley with almond and walnut trees and vineyards near Ercus on our way to Hasankeyf.

Hasankeyf

The Tigris runs past the town Hasankeyf; from there it flows southwards in serpentine curves, on lands which have hosted so many civilizations and have been a battleground between East and West. Barges for trade and transportation once plied the waters of the Tigris, and royals set up thrones to rest in the cool breeze of the riverside. The golden years of Hasankeyf were under the reign of the Artukids between 1100 and 1234. The town remained under Ayyubis sovereignty from 1234 until the15th century, when Ottoman rule commenced.

An engineering feat of its time, a monumental stone bridge with ten arches was built by the Artukids over the Tigris. The legs of the old bridge stand in the water, parallel to the modern bridge, as a reminder of the town's glorious past. The ruins of the ancient city are on the hills overlooking the Tigris. Tombs, mosques, medreses and palaces dominate the river view. Six thousand caves lurk in the high hills, which are believed to have been a center for ancient cave-dwellers. The rocks on the skirts of the hills are soft and easy to tunnel in. It is believed that they may have been made by people seeking security or religious retreat. The residents of Hasankeyf lived in these cave-homes until the 1970s. Today, they live in a village on the bank of the Tigris. They use the caves as barns or stables, and even as souvenir shops, cafes and restaurants.

At the end of the 20th century, Hasankeyf came close to being flooded by the waters of the Tigris and the Ilisu Dam. The dark days of flood-watch drew journalists and TV cameramen from far and wide. Under the media spotlight, the town became a focus of interest for both local and foreign tourists. Until 2000, Hasankeyf was a town where teachers, military officers and the police, as civil servants, went for duty.

The increased tourism seems to have benefited the children. They have learned to communicate with tourists, and give them information on historical sites in the language of their choice, English or Turkish. They recite everything by heart. Boys also sell postcards and books, while girls sell the local craft, uzeri, made by stringing dry chickpeas interspersed with colorful ribbons. Uzeri is a decorative folk item that brings good luck to one's home. After a little girl assured me that she herself had crafted the pieces she was selling, I bought one with pink and blue ribbons.

The flow and smell of the river, fishermen throwing nets over the river and catching shebot, the local fish, and tranquil tea gardens with hammocks are all part of daily life in Hasankeyf. People walk down to the river banks in summer, when there is less water, and set up thrones for rest and relaxation. These high thrones also protect them from scorpion bites. The river, set amidst impressive history, is also a draw for tourists. Since our tour was over a holiday week-end, there were many school groups around. I pledged to return to this town on a weekday, when not as many tourists would be around, but also soon, before rising waters seal its fate.

Diyarbakir

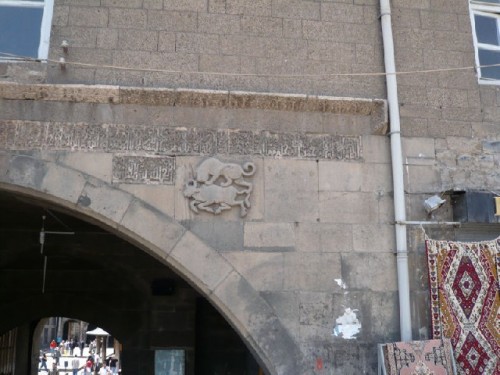

Diyarbakir, northwest of Hasankeyf, was our departure city for Istanbul. A major city within walls, with eighty-two towers and seven gates, built by the Roman Empire in 369 AD, it has a large Kurdish population. We entered the city just as the noon prayers ended. Men in skullcaps poured out of Ulu Cami (the Mighty Mosque) into its large courtyard surrounded by arches. As they walked toward the street, with prayer beads in hand and some supporting canes, they signaled that we were in a very traditional city; the few women around were mostly wearing long coats and headscarves.

Ulu Cami is the centerpiece of an architecturally rich religious complex. The courtyard is surrounded by buildings constructed with black stone and basalt and ornamented in carved stone relief. At ground level the buildings have niches for sitting, and their windows are behind latticework. In the center of the courtyard are two impressive ablution fountains with conical, segmented copper roofs supported by stone columns.

A brief walk outside of the mosque complex was enough to convince me that this was a city I wanted to explore at leisure, and not on the way to the airport. Diyarbakir's famed copper and kilims, as well as its kadayif shops beckoned. The kilim is a flat-weave carpet, as opposed to rugs, which are knotted. Kadayif is a sweet made of roasted shredded wheat soaked in syrup and topped with ground pistachio nuts.

Those tempted to travel on a similar itinerary need a minimum of five days; the three days we had did not do justice to the cultural richness of southeastern Turkey.