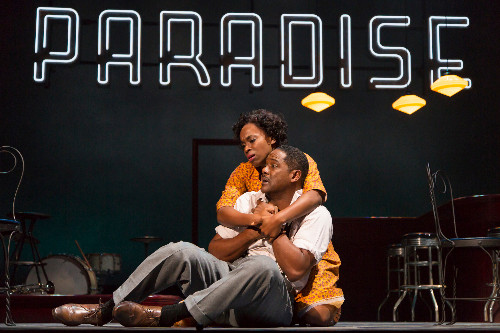

Blair Underwood in Paradise Blue

World Premiere at Williamstown Theatre Festival

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 24, 2015

Paradise Blue

By Dominique Morriseau

Directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson

Sets, Neil Patel; Costumes, Clint Ramos; Lighting, Rui Rita; Sound, Darron L. West;

Co-composers, Kenny Rampton and Bill Sims, Jr.; Fight Director, Thomas Schall;

Cast: Blair Underwood (Blue), Krtistolyn Lloyd (Pumpkin), Keith Randolph Smith (Corn), Andre Holland (P-Sam), De’Adre Aziza (Silver)

Main Stage

Williamstown Theatre Festival

July 22 to August 2, 2015

World Premiere

With the opening last night of Dominique Morisseau’s Paradise Blue there was a by now familiar pattern.

The fourth production of the Williamstown Theatre Festival yet again presented a world premiere with marquee stars, in this case stage and television star, Blair Underwood, and Tony nominee, Theatre World and Obie winner, De’adre Aziza.

In fact the only non premiere of new artistic director Mandy Greenfield’s season will be Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten, starring diva Audra McDonald with Long Wharf’s director Gordon Edelstein.

By now we have come to realize the risk taking of this approach. Coming into the fourth production of the season WTF is still looking for a hit. Despite the all star casts, which stimulated strong advance ticket sales, the shows thus far have received mixed reviews from mainstream critics.

While Paradise Blue is an uneven drama, judging by the spontaneous standing ovation following an explosive surprise ending, this may be the much needed tipping point for what until now, despite those marquee names, has been a less than stellar WTF season.

There are outstanding performances and fine moments in this play but the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

For most of the first act the pace is enervating with inarticulate and barely audible dialogue. Too often the actors converse with each other rather than project to the audience. Add to that the patois of black jazz musicians and hipsters hanging out in a Detroit nightclub in 1949. It is not a dialogue that falls easily on the ears of a mostly senior honkey audience in the bucolic Berkshires.

For opening night there was a solid representation of brothers and soul sisters in support of fellow artists and families. Significantly, this segment of the audience often cracked up to jive that fell flat on ofay ears. This provided a reality check for the intentionality and homey humor of the production.

Lines by P-Sam address this directly. He wants to hang at the Paradise rather than take another gig with a white big band shucking and jiving for squares. This is another fine role for Andre Holland who plays a black doctor in a turn of the century white hospital in “The Knick” on Showtime

According to program notes the award winning playwright, Morisseau, states that with her cycle of plays she wanted to create for the much maligned Detroit, or Motown, what August Wilson achieved for Pittsburgh through his Century Cycle of ten plays marked by decades.

Set in Detroit in 1949, as was happening all over American the African American Blackbottom neighborhood of homes, theatres, jazz joints and mom and pop stores was about to be obliterated by urban renewal.

This bulldozing of ethnic and working class communities did irreparable damage to the American cityscape. The concept was that new and progressive development would replace beaten down real estate but that never happened.

Here in North Adams what was once a vibrant and dynamic community turned into now struggling malls and vast parking lots. In Boston that entailed the West End, a multi-ethnic neighborhood and notorious Scollay Square, a destination of bars, strip clubs, flop houses and tattoo parlors for sailors on leave during WWII. They were knocked down and replaced by bland high rise luxury apartments and the vast wasteland of Government Center.

The Paradise which Blue (Underwood) inherited from his father is at the epicenter of the city’s plan to level Blackbottom. It is key real estate in a central location. With a domino reaction if Blue, who is keeping the information to himself, takes the deal for $10, 000 and splits to Chicago to escape his demons, well then, there goes the neighborhood.

As blues master Robert Johnson would say Blue "me and the devil living side by side" with a hellhound on his trail. For most of the play, up to that explosive climax, we find it hard to fathom the how and why of what ails him.

In the opening segment of the play he has just fired the bass player for his bop quartet. His drummer P-Sam and pianist Corn (Keith Randolph Smith) are keen on finding a replacement. Until then they are out of work but still tenants of Blue’s club and boarding house.

As cook and chamber maid the simple and dreamy Pumpkin (Kristolyn Lloyd) is sweet, lovable and innocent. Going about her chores she pauses to recite poetry. There is a mismatch as this domestic woman, a servant at best, is the love interest of Blue the brilliant, handsome, and volatile trumpet player and hipster. We fail to feel what he sees in her; particularly his ambition that with the help of Corn she will develop as a singer for his band.

While we try to cop to the ragtime between Corn and P-Sam, with their riffs about the fate of the Paradise, the first act slogs along at a snail’s pace.

Given a sparing production with more props than set by Neil Patel we wonder why this production is blown up to the Main Stage? It might have been more cozy and intimate in the Nikos theatre. Mostly this feels like a small play. With closer proximity the audience wouldn’t have to struggle to follow the sotto voce delivery of a conversational script.

Then Lordy oh Lord enter the hip swinging merry widow spider, the campy and vamping, knock down drag out femme fatale, a voodoo lady from the Bayou, De’adre Aziza’s Silver.

From the get go she is a woman of mystery who eats men alive. In the back story she has been in fifty cities where she has bedded fifty men all of whom are dead, dead, dead. From those alleged scores she arrives in town, strictly solo, and with a Chelsea roll thick enough to choke a horse.

But Blue will have none of her charms and con. Just show me the money he demands when she wants to rent a clean room with three square. That’s five bucks a week in advance he demands. I can get it for $3 up the street she retorts. But the spider has an agenda for wanting to stay at The Paradise. Up front she peels off $30 which was mega bucks back in the day.

When she pushes Blue, in no uncertain terms, he says that he will throw her out on her ass the minute she steps out of line.

Like Garbo she vants to be alone. Pumpkin will bring meals to the room.

Slipping into something comfortable Silver strips down to a black lace bustier and garter belt with nylon stockings and a silk kimono.

Oooohhhweee. Both P-Sam and Corn want a taste.

Oddly, it’s the heavy set and homely Corn who scores. The seduction, in which she is the aggressor, is the best scene in the play to the delight of the audience. He has not enjoyed the scent of a woman since his wife passed away three years prior.

Packing a wad she has designs on buying the club. That is also the plan of P-Sam who enlists Corn to soften up Blue on that riff.

Out the door to bet on the numbers he asks Silver for her mojo. He is spooked when she suggests “131.” Corn explains to her the bad luck of playing 13. But with or without her number P-Sam scores and now has the cash to bid for the club.

Evoking the small combos of bop which followed the big bands of the swing era there is a lot of jazz in this production. Much of which comes with Underwood faking playing. This was precisely composed and recorded by Kenny Rampton and Bill Sims, Jr. There are a lot of gaffs as Blue never plays a straight tune. With a hand over the bell he simulates a plunger mute bending blues notes.

He appears to struggle and fumble through arrangements. The playing entails bits and pieces including some mad sequences. That takes crisp timing as well as difficult collaborations between the director, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, Underwood, and the musicians. Much of this is handled brilliantly.

The theme of bop is conjured with another clever device. The daughter of an abusive blues man Silver grew up with music. She travels with a portable turntable and a stash of 10" classic LPs of Charlie Parker and Lester Young. It reminded me of a key scene in The Connection, a 1959 Jack Gelber play, and Living Theatre production. A junkie shows up in the pad unrolls a cord, plugs in the record player, grooves to a riff by Bird then departs.

It was cool to hear classic jazz. But in Williamstown? Hey man, as cats say, never hip the squares.

Given the far out aspects of a mostly titubating play I wondered what the audience was getting off on?

There are then different ways to slice this pie. It definitely helps if you’re hip to the jive and dig bop. Even if you do, however, there are plot points that don’t make sense.

Given an ambitious but uneven premiere in Williamstown, with some tightening up, this play is likely to have more productions. It makes me want to see the other plays in Morisseau’s Detroit cycle. The first is Detroit '67 which premiered at Public Theatre in 2013 . The third Skeleton Crew will have a 2016 production at Atlantic Theatre Company.

This trilogy puts a hard luck city on the cultural landscape. Morisseau shows us the love.