Bethel Woods, Celtic Woman and a Dancing Cat

A Woodstock Pilgrimage

By: Ien Nivens - Jul 26, 2010

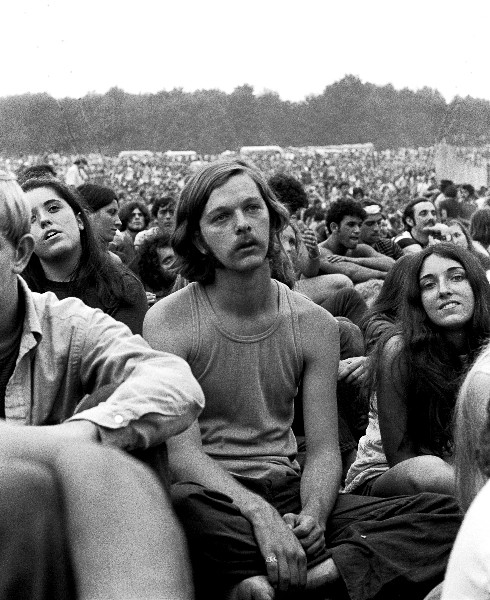

A generation ago, four “young men with unlimited capital” invested in a new kind of American idealism. Fueled by ancient and modern chemicals, a nation of innocents heeded their call and converged upon the gentle hills of Upstate New York for the sake of three values that were, in that time and place, virtually indistinguishable: peace, love, and rock-and-roll.

Place names sometimes—often with a degree of geographical approximation—become synonymous with events. Think Gettysburg, Valley Forge, Tienanmen Square . Same difference at Woodstock, with an emphasis on the difference, since no literal battle took place. Instead, the icons of the Age of Aquarius dropped in, tuned up and turned Woodstock into the household name for an event that has come to symbolize a generation of unrest. That is, the event was supposed to be held at Woodstock, but nerves got the better of the original hosts, and the festival got shifted some forty miles southwest, to Yasgur’s Farm in Bethel, where the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts now holds the high ground.

We made our first pilgrimage there last Saturday to visit the Museum at Bethel Woods' permanent exhibit, “Collecting Woodstock” and to sit in on Celtic Woman’s outdoor performance of “Songs from the Heart”.

“Collecting Woodstock” is an immersive work-in-progress. Less a collection of artifacts than of information, the multimedia exhibit documents a decade of civil discontent with the sights and sounds of celebration and anihilation, ascension and assassination, idealism and disillusionment. Nothing much has been sanitized, except inasmuch as time has distanced us from the immediate conditions of psychedelic squalor that characterized a generation and that necessarily prevailed when “we were half a million strong” and gathered in a field some 15 acres square. “Collecting Woodstock” marks the raw power of youth and naivete to bring an end to a war that had no honor in it, to advance the integration of a nation still divided by race and gender, to dismantle an administration if not a government, and to expand the spiritual consciousness of a species beyond the firmly established limits of nationalism, sectarianism and chauvinism so prevalent in the power structures of the 1950s. It is impossible to imagine life in the United States today without that shift in thinking, and it is impossible to imagine that shift coalescing without the catalyst provided by four young venture capitalists who wanted to invest in a recording company and thought a music festival might be a good way to get started in business.

In the sixties and seventies, influential writers like Kurt Vonnegut were calling for a new religion. In spite of a backlash of fundamentalism across the midsection of this country, for all intents and purposes, we have one. Our early hymns were played here, and they paid homage to an older set of gods and goddesses that have remained with us, waking us a little at a time to the needs of the earth and of humankind. The relics being gathered at Bethel Woods, where they are housed in a modest chapel on a hill, will help to preserve and to disseminate the articles of that faith, to stir the memories of some and the imaginations of others.

The big ticket show this mid-season seems, at first blush, out of joint with the doctrine of Woodstock. But in fact, Celtic Woman celebrates an aspect of the maturation of the vision of harmony—in Eire as it is in America. Four young women, backed by big capital and possessing unlimited optimism, with faces as fresh as dew and voices at times ethereal, with hints (but only hints) of the enigmatic about them, always powerful in their theatricality, bear none of the scars, it seems, of a country so recently at odds with itself. Like Bethel Woods, Celtic Woman is a multi-faceted jewel in a complicated setting. There is more blood in the eyes of their music than its presentation would have us believe, and in that fierce blood lies its most amazing grace.

Much of the show’s fire is provided by the violinist, Mairead. (The principle performers seem to have only first names.) Of the four women, she most embodies the energetic mystery at the heart of Irish survivalism. She is unclouded by despair. One wonders if, in fact, she hasn’t appeared on stage by some transactional kind of magic, a substitution of some sort, between the realms of high commerce and Faerie.

We are seduced in fields of barley, haunted and taunted by Antony Byrnes’ brief strains of introduction on the bagpipes to Galway Bay, feel a new vocal power invested in the otherwoldly currents of Enya’s “Orinoco Flow” and get caught up in the controlled complexities provided by the newest member of the ensemble, Lynn, with her sweet, shy undertones that seem, at times, a little distanced from the rest of the group, as if she hasn’t found her way among them yet. While Lisa seems the most conversant with the inherent lyrical honesty of the offerings, both she and Lynn stand back a bit, not pushed aside by, but ceding ground to the youthful ebulliance of Chloe, whose affectations belie a concern with wringing emotion from an audience already drenched in it.

“Danny Boy” is a given. Nevertheless, there is an originality to Celtic Woman’s version of the classic, in which Mairead supports the vocalists, harmonizing with their clear pipe and warble to render the staple a centerpiece of the performance rather than a mere cliché. It was followed up dramatically with “Mo Ghile Mear.” A voice in the crowd calls out, “The boys are at it now!” and the drums rumble forth to rouse us out of melancholy.It is, in fact, when the boys are at it, that Celtic Woman comes full-bodied to the stage, sexy, flirty and gamine, with its men to set it off and make it shine against the shananigans of their whistles and pipes and the rattle of the bodhran.

After intermission, Lynn took the stage and her rightful place among the other women. While each of them nodded in her own way to the place and its history, it was Lynn’s winsome admission that she’d have preferred to be singing Joni Mitchell here that leads one to wonder what might happen if the lasses were, in fact, empowered enough to deviate from the Celtic Woman script.

As an aside, if you should make your own pilgrimage to Bethel Woods, you would do well to stop in at The Dancing Cat Saloon and Distillery, just outside the entrance, on Route 17B. While the menu, so far, is succinct, and the distillery is still being built, the restored American-Victorian ambience of the saloon itself is charming, airy and hospitable, and the sandwiches are delicious. Listen, I’m not in the habit of raving about a reuben, but the Dancing Cat has got it right, down to the cole slaw (not too sweet and not too wet) and the mustard (creamy, with—was that a hint of horseradish or wasn’t it?) And the fries? Have the fries.

When the cat gets dancing, we’re told by co-proprietor Stacy Cohen, local farmers’ crops and orchards’ fruits will be distilled in the 5,000 square foot facility adjacent to the saloon as hand-crafted vodka, baby bourbon, gin , whiskey, brandy and grappa. Steam produced by the distilling process will heat the floors, and local talent will provide the entertainment.