Bill T. Jones Celebrates John Cage Centennial

Story/ Time at Jacob’s Pillow

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 29, 2012

Story/Time 2012

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company

Executive Artistic Director, Bill T. Jones

Associate Artistic Director, Janet Wong

Producing Director, Bob Bursey

Conceived and Directed by Bill T. Jones

Choreography by Bill T. Jones and members of the company

Text, Bill T. Jones

Music, Ted Coffey

Décor, Bjorn Amelan; Lighting Design, Robert Wiersel; Costume Design, Liz Prince; Associate Set Design, Solomon Weisbard

Company: Antonio Brown, Talli Jackson, Shayla-Vie Kenkins, LaMichael Leonard, Jr., I-Ling Liu, Erick Montes, Jennifer Nugent, Joseph Poulson and Jenna Riegel

Five years ago, Bill T. Jones (born 1952), one of the most successful and celebrated dancers and choreographers of his generation, with more than 100 works created for the Bill T. Jones/ Arnie Zane Dance Company (founded in 1982), retired from performing. He continues to choreograph for the company.

This week he was back on stage at Jacob's Pillow for a 2012 work Story/ Time.

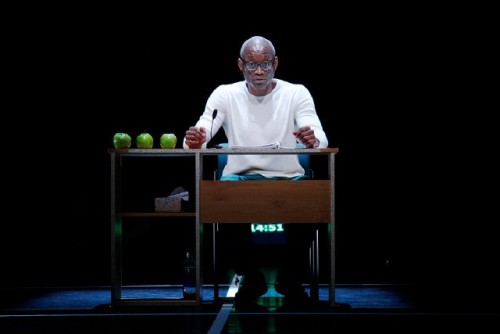

He was not dancing with that magnificent, fluid, tall, sculpted body. Jones was seated behind a desk with several green apples reading 70, one minute, prose pieces selected by chance operations in homage to John Cage (1912-1992); the avant-garde musician, poet, artist and noted authority on everything from Zen Buddhism to hunting and preparing wild mushrooms.

Heavily influenced by the I Ching or Chinese book of oracles, and its hexagrams determined by tossing yarrow sticks, Cage incorporated chance and serendipity into his work. Often his music, or more correctly range of sounds, was combined with dances created by Merce Cunningham (1919-2009). We were fortunate to see the Cunningham company at Jacob’s Pillow on the weekend of his death.

During their early years at the legendary Black Mountain College, Cage and Cunningham traveled in a VW Bus with the young artist whom they met there, Robert Rauschenberg, who designed sets and costumes for the company.

Like Ken Kesey’s Magic Bus this traveling company comprised the merry pranksters of the avant-garde. Their works were innovative, difficult to comprehend, and often flat out outrageous. They routinely pushed the limits for audiences. Early on, they mostly toured college campuses.

In the PBS video on Cage that I showed to an annual avant-garde seminar at Boston University the three, when interviewed, were full of mirth and humor about those early years. There was a falling out with Rauschenberg by then reconciled.

When Cage was in Boston making edible papers with Rugg Road (Bernard Toale and Joe Zina) I got to know him and posted an item in Art News. On a number of occasions I was absorbed by his warmth, humor, generosity and humility.

Which are not notable aspects of the gravitas of Jones. Compared to Cage’s halting, endearing, stutter step readings and lectures, Jones speaks with elaborately articulated, dramatically pregnant, enunciation. There are occasional smiles but none of the wit and self deprecation that made Cage so endearing. It was a quality that made us really want to follow along with his outrageous and often demanding creations.

Now 60, what we saw at Pillow in Story/ Time represents a shift in the creative mandate of Jones. The work has ranged from dance with strong social and political themes of gender and race, to two Tony Awards, for the Broadway shows Spring Awakening and Fela.

This latest work, with Jones morphed from dancer to on stage narrator, fully embraces the concept of chance operations developed by Cage and Cunningham. They often worked independently but together. Cunningham did not dance to the music/ sound of Cage but rather with it. There was a simultaneity rather then synchronicity. There were parallel creative streams, music and dance, with no deliberate attempt at confluence. One had to focus on two different elements simultaneously.

Often this was simple and almost primitive. In one such collaboration, Cage created a score with the amplified sound of a feather scratching a cactus, while Cunningham executed a solo dance. It was ok to find such efforts droll and charming.

While, in this new work, Jones follows Cage’s adherence to chance operations, he missed its whimsical, Zen spirit. The text of 70, one minute readings were selected from a greater number by a random process. That was combined with the music/ sound of Ted Coffey and the responses of the company often were contained but not limited to a grid of squares on the floor of the stage. There were some props like a couch which was moved about and large, transparent, white, folding screens. These created cubicles which dancers were seen through.

Cage was a diarist and Jones, in several of the minute pieces, referred to listening to and responding to Cage’s deadpan, absorbing readings. It takes considerable patience and endurance to sit through Cage’s CD’s.

It was while listening to Cage’s diary recitations that Jones informed us he decided to write his own. They also often read like diary entries entailing vignettes of global travel and interactions with jazz and art world celebrities. Like giving permission to Robert Mapplethorpe to photograph him nude but not show his penis. Or viewing prostitues in windows in Amsterdam. There were several tales set in Copenhagen. Some stories entailed what appear to be estranged interactions with siblings, extracts from the Bible, or stories about racism and oppression. At times they evoked silence or abstracted sounds and even the folk/ blues classic “John Henry.” Only a couple of times the audience laughed at intended humor.

There were poignant memories of his partner Arnie Zane (1948-1988). One told of how Zane tricked his way into an opportunity to photograph the sculptor Louise Nevelson. Another related the beauty of snow on bamboo in Japan, in March, trumped by memory of the death of Zane at 39.

Following his death, Jones choreographed Absence, a piece that evoked the memory of his late lover and partner. Absence addresses the varied feelings associated with mourning. After a 1989 performance of Absence, writer Robert Jones described the piece as "a shimmering, ecstatic quality that was euphoric and almost unbearably moving." Tobi Tobias, dance critic for New York, said that the work took "its shape from Zane's special loves: still images and highly wrought, emotion-saturated vocal music."

A later, related piece found Jones at the center of controversy. On April 23, 1995 Jan Bresualer reported in the Los Angeles Times “…choreographer Bill T. Jones--best known to those who didn't know him before as the artist whose interdisciplinary dance work ‘Still/Here’ sent shock waves through the media and beyond when it had its U.S. premiere in New York in November.

“The work, which, in addition to dance, includes video segments of people who have been diagnosed as terminally ill, became the center of an ongoing debate about ‘victim art,’ sparked by a commentary by Arlene Croce in the Dec. 26-Jan. 2 issue of the New Yorker. Croce, the magazine's longtime dance critic, refused to see or review ‘Still/Here’ on the grounds that its subject and treatment placed it outside the boundaries of criticism. Many heated responses followed in an array of publications.”

How long is a minute Jones asked the audience as an exercise to get us in the mood? Hands went up at staggered intervals. Astrid raised her hand at the precise minute. I was astonished at her precision. For me, the passage of time, the measure of a minute, is more difficult and agonizing.

A minute can be a blip, a moment of orgasm while making love, or interminable while enduring a dental procedure.

As T. S. Eliot wrote “ And indeed there will be time For the yellow smoke that slides along the street, Rubbing its back upon the window panes; There will be time, there will be time To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet; There will be time to murder and create, And time for all the works and days of hands That lift and drop a question on your plate; Time for you and time for me, And time yet for a hundred indecisions, And for a hundred visions and revisions, Before the taking of a toast and tea.”

According to Shakespeare “Time does make cowards of us all.”

The Book of Ecclesiastes. "A time to..."

So 70 minutes precisely.

Four minutes on, however, Jones stopped informing us that none of the clocks on stage were working. “That’s show biz” he said walking off while the house lights came up.

Time became how long will we wait, if ever, until the performance resumed?

When he continued we saw projected on the back of the stage a digital clock reading 0:00. We wondered if, like during a football game, it would be reset? Instead, Jones started again from the beginning repeating the now familiar first four selections. We watched the seconds click away noting that there were occasional gaps and pauses while, at other intervals, the text was spoken through sometimes spilling over for several seconds.

One tried to focus on each minute's selection. There was no perceived continuity of text although over the course of the reading one sensed clusters of related segments which were likely to have been created in sequence. Like recollections of surprisingly harsh sibling stories.

In the Cage/ Cunningham paradigm there were several elements to absorb simultaneously. For the first twenty minutes we watched the clock. The dance and sound were simple and subordinate to the telling of episodic, disconnected tales. The reading dominated the experience. Both the costumes by Liz Prince and the choreography evoked a rehearsal room.

At the 20 minute mark the clock disappeared. For me it evoked a panic reaction. Now I was adrift with no instrument to measure the passage of time. The only indicator was the turning of a page. One might have counted to keep track of the minutes.

While swirling about in a vortex of disoriented time the dance and music also became more dramatic and complex. Here there was a generational paradigm shift from historic Cage and Cunningham to full blown Jones. Fast forwarding from a lulling monotony we found full measure of that magnificent company and his inventive chorography. We lost the limit of the grid as the dancers explored ensemble passages including individuals leaping like cheer leaders into the arms of their comrades or being lifted aloft in Statue of Liberty clusters. There were some costume changes. Then a passage inspired by a family incident of rolling along the stage; complemented by smoke, lighting effects, then two nude figures, a man and a woman.

The sound/ music rose to a cacophony at times staggered about the space from different, separate speakers. It totally drowned out whatever Jones was reading. The text was subsumed into something else going on. We swirled into an aesthetic maelstrom. Like Dorothy swept up in Kansas and set down in Oz.

Then, at the 67 minute mark, the clock returned. Aha. Three minutes to go.

The first two passed in silence. Would that be how the performance played out? Then, one last story. That final minute clicked down with an anecdote.

Followed by thundering applause and a standing ovation.

It had indeed been an astonishing voyage through a warp of time and space. If, at 60, Jones is reinventing himself one eagerly anticipates what follows. The man is a genius and he knows it.