Dolores

World Premiere at West Edge Opera Honors Distinguished Labor Leader

By: Victor Cordell - Aug 03, 2025

History is written of leaders – presidents, generals, popes. Second-in-command, deputies, assistants, are largely forgotten. The Delano, California grape pickers strike and boycott to challenge deplorable working conditions that became a major event in the modern American labor movement, began in 1965, started by Larry Itliong’s Agriculture Workers Organizing Committee. That organization soon merged with the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), led by César Chavez, and the latter would become the combined leader and the face of the movement.

Dolores Huerta was Chavez’s closest and most trusted associate, independently leading strikes and boycotts and negotiating the contract with the farmers that would end the strike in 1970. Though well known to those with deep knowledge of labor movements, Dolores remains unknown to the general public, overshadowed by the recognition of Chavez.

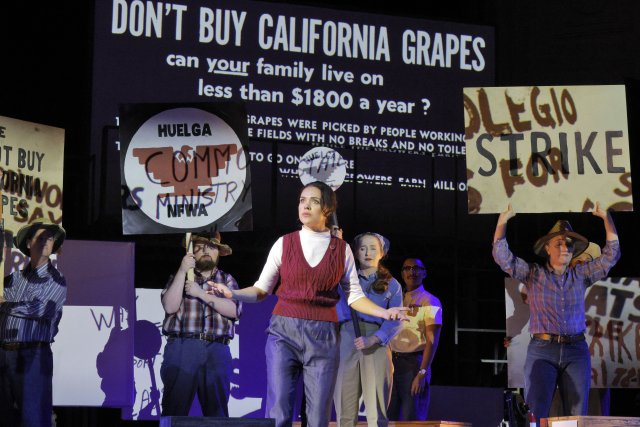

In conjunction with composer Nicolás Lell Benavides and librettist Marella Marin Koch, West Edge Opera presents the world premiere of the opera Dolores. This counterbalances the lack of acknowledgement received by the title character – at least with the opera company’s audience, along with those of co-producers Opera Southwest and San Diego Opera. The result is a powerful narrative supported by vibrant music that should have legs but can benefit from minor adjustments. Staging adds to the effect with energetic strike and boycott scenes, supported by accompanying video projections.

Benavides’s music is blessedly tonal and fitting to the situation – often ominous, and sometimes consoling. A full sound is developed by Conductor Mary Chun’s small orchestra, but the highlights tend to occur in various solo segments, a particularly appealing one being a haunting viola solo that accompanies Huerta’s sadness as she pines for her seven children that she seldom sees because of the demands of her job as a union executive.

The central moral drive of the opera concerns clashes associated with trying to do good things, with sacrifice being the operative condition. People of good intentions often clash because they differ somewhat in objectives or see different ways to accomplish the same thing. But even more discordant are the internal conflicts. Often fighting for one good goal results in sacrificing another, and successful people constantly must deal with these tradeoffs. This story is specifically about those who sacrificed by striking and placing themselves and their families in jeopardy for several years. It may be hard to believe or remember, but this strike went on for five years.

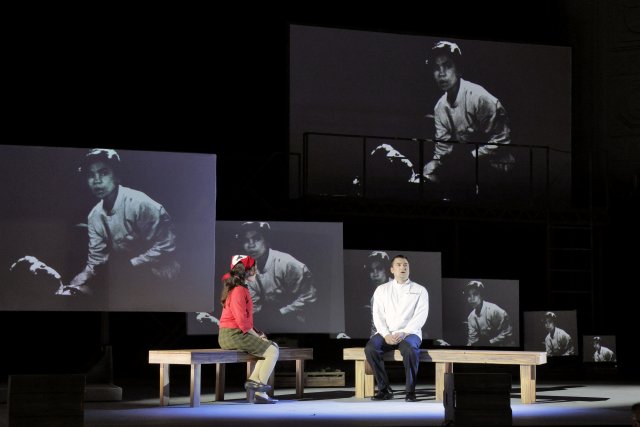

Much of the plot line deals with the relationships among the leaders in the movement. Huerta is well represented by soprano Kelly Guerra who sings with conviction and shows her character’s passion. Phillip Lopez as César Chavez and Rolfe Dauz as Larry Itliong give good depictions of their characters as well. But vocal pinnacles came from featured players. Sam Faustine as Tricky Dick (the program designation) produces a clarion tenor and an over-the-top depiction of future president Richard Nixon, while Alex Boyer serves well with his always strong voice as RFK.

An interesting strategic decision was to place the opera in 1968, already three years into the strike and with three harvests rotted on the vine, in order to make the leadup to and assassination of Bobby Kennedy in Los Angeles the centerpiece. As the opera’s narrative attests, RFK had allied with NFWA; personally visited Delano to break bread with Chavez to end his 25-day hunger strike; and had Huerta on the dais with him on the fateful day.

However, the focus on Bobby and the run time accorded deflects much attention away from Huerta. Notwithstanding, a great deal of emotional impact results from reliving this tragedy. But, overall, the plotline does drag a bit, and could be trimmed and recentered on the title character and more reference to the early stages of the movement.

We can all conclude that the war for higher moral objectives is never over, as we are in a period of serious backsliding presently. Nonetheless, victories can be declared. It was disappointing to find the lack of closure in the opera concerning the strike and boycott, and that Huerta’s contributions are underrepresented. Despite all of the gains from the negotiated contracts that ended the unrest, we are left with a feeling of failure.

Another point, and I just made a similar comment in another review, programs and supertitles should not be stingy in identification. For instance, character surnames are not mentioned in the cast listing, nor are characters always identified in the supertitles when they first appear. Brevity is not always a virtue, and producers should not expect all operagoers to have in-depth knowledge in these fringe areas. Don’t leave them in the dark.

One delight that presumably only opening night attendees will enjoy is a stage visit from the spry and cogent 96-year-old Dolores Huerta after the performance. She spoke to the timeliness of the opera given deplorable current immigrant, labor, and other conditions in this country and of a job not yet completed. She stoked the crowd which responded with peals of her dictum, “Si, se puede!” (Yes, you can!).

A final point is that unfortunately, many people in the U.S. have unfavorable attitudes toward labor unions, fixated on relatively rare featherbedding and overly generous contracts. Stories like this one and of the deaths of 146 workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 that also resulted in improved working conditions are important to demonstrate the dignity that unions have brought to the working class.

Dolores, composed by Nicolás Lell Benavides with libretto by Marella Marin Koch and produced by West Edge Opera has its world premiere at Oakland Scottish Rite Center, 1547 Lakeside Drive, Oakland, CA through August 16, 2025.