Verdi's Don Carlo at Tanglewood with Levine and the TMC Orchestra

Zelijko Lucic and Luciana d'Intino excel in an uneven cast

By: Michael Miller - Aug 04, 2007

Tanglewood FestivalSaturday, July 28, 2007, at 7:30

The Leonard Bernstein Memorial Concert

For the benefit of the Tanglewood Music Center

TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER ORCHESTRA

JAMES LEVINE conducting

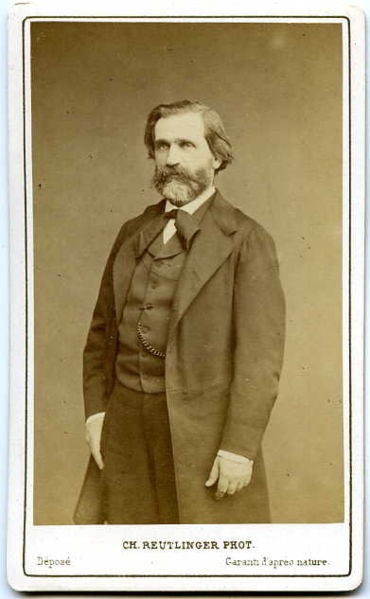

GIUSEPPE VERDI

Don Carlo, Opera in four acts

Original French libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, after the play by Friedrich Schiller

Elisabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II of France - PATRICIA RACETTE, soprano

Princess Eboli - LUCIANA D'INTINO, mezzo-soprano

Don Carlo, Infante (Crown Prince) of Spain - JOHAN BOTHA, tenor

Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa - ZELJKO LUCIC , baritone

Philip II, King of Spain (Carlo's father) - JAMES MORRIS, bass

The Grand Inquisitor PAATA BURCHULADZE, bass

The Count of Lerma - DAVID WON, baritone

A Monk - EVGENY NIKITIN, bass-baritone

Tebaldo, Elisabeth's page - KIERA DUFFY, soprano*

A Celestial Voice - ILEANA MONTALBETTI, soprano*

A Royal Herald - CHRISTOPHER JOHNSTONE,

baritone*

Flemish Deputies Mischa Bouvier, Christopher Johnstone, Giles

Tomkins, Michael Weyandt, and Matthew Worth, baritones*; Ulysses Thomas, bass-baritone*

Eight Monks Mark Gianino, Elliott Gyger, Jeramie D.

Hammond, G.P. Paul Kowal, Timothy Lanagan, David K. Lones, Donald R. Peck, and Michael

Prichard, basses†

Monks, court attendants, populace . . . TANGLEWOOD FESTIVAL CHORUS, JOHN OLIVER,

conductor

Following an evening of intense listening to Alexander Zemlinsky's two brief, concentrated, and fast-moving one-act operas at Bard, Verdi's Don Carlo impressed me with its vast scale, the "heavenly lengths," through which the composer expressed the grandeur of his model—both Schiller's play and Schiller's vision of humanity—as well as the bleak lives of the protagonists, oppressor and oppressed alike, all trapped in the stalemate created by arbitrary power and its consequences—which may or may not precede a revolutionary storm. To my mind, it is Verdi's greatest opera before Falstaff—or Otello, perhaps. While those wonderful final works point in the direction of the economical dramaturgy of the 20th century, Don Carlo follows an expansive course Verdi adopted relatively seldom, for example in La Forza del Destino, but nowhere in Verdi's oeuvre is this vastness so essential to his purpose. Don Carlo's amplitude as a theatrical work, as well as the monumentality of the individual arias are necessary for us to grasp the pain of these thwarted lives and the reach of their memory and their waiting.

I'm especially fond of this melancholy work, and I try to see it wherever I happen to be within access, which is usually at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where James Levine performs the five-act Paris version of 1867, sung in Italian and merged with later revisions, which he introduced in 1979. This performance by the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra under Mr. Levine's direction was of the later Italian version, omitting the Parisian first act, which begins with the encounter of Don Carlo and Elizabeth in the garden of Fontainebleau. This original version puts Don Carlo and his love for Elisabeth very much in the foreground, and it opens the opera with an atmospheric romantic scene. Since this first version was resurrected after years of neglect, we all tend to treat it with awed respect. After some years of living with the Paris version, I must say I am very happy to hear the four act version under Mr. Levine's masterful and enthusiastic direction. It gets us directly into the crux of the story and offers a more ambiguous and more gripping dramatic situation, with Don Carlo somewhat reduced in stature in relation to King Philip, the Marquis of Posa and the others.

Verdi wrote for a grandly decorated stage with costumed singers and choruses, but some of his operas can be almost more powerful in concert performances. I was once particularly impressed by a film of Toscanini's Studio 8H performance of Aida, which became a gripping psychodrama when stripped of its horses, camels, and elephants. Perhaps Don Carlo, with its larger cast of principals is less fully realized in concert, but certain qualities, compromised in the opera house, came out at Tanglewood, above all Verdi's magnificent orchestral writing. Even with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, which Levine has trained for years, I've never quite heard the dark sonorities and energy I heard in this performance, thanks partly to the enthusiasm and brilliance of the young musicians of the TMC Orchestra, the incomparable singing of the Tanglewood Music Festival Chorus, and partly to the grand acoustics of the Music Shed.

The Koussevitsky Music Shed was above all a fine venue for this impressive gathering of forces, probably too vast for even the Met. We all came there to hear Don Carlo with all those particular qualities which are lacking in even the best opera houses in the world. The discipline of ensemble and balance and the rich sonorities that are impossible in a opera house. In that, I don't believe the fussiest critic could have been disappointed. The TMC Orchestra were truly amazing in their commitment, enthusiasm, and their ability under Levine's direction to explore under-recognized inner voices in the score.

Whatever shortcomings there were lay in the operatic stars who sang the principal roles. James Morris, who is so highly respected around the world for his Philip, seemed constrained, as solid and grand as he was, but not quite up to the very moving performances he has given on the stage of the Met. I fancied he was feeling uncomfortable without the stage and its props, but who knows? Johan Botha, another singer I greatly admire and have praised enthusiastically in recent months for his Florestan and Walther von Stolzing, seemed miscast as Don Carlo. In this role of the neurotic , immature Infante, who is driven primarily by his impossible passion for his former betrothed, now his step-mother. Botha had impressive control of dynamics and phrasing, and no one can say that his interpretation was unintelligent, but his steely heroic voice lacked the vulnerability the role needs. His performance was very fine, but it wasn't Don Carlo. Against Botha's monumental Don Carlo, a recessive Elisabetta was cast. Patricia Racette seemed to lack the power of characterization and vocal production for the role. Her attractive voice, which needed a bit of time to come together, lacked the force a Verdian heroine needs. I was astounded when Ms. Racette sang an exquisite final scene. Here everything was right and very moving, and of course she brought the house down with appreciation. Even the hitherto stolid Botha melted a little. But what was she up to before? Was she saving her voice, or what? In her earlier scene she was lacking in presence, projecting a rather monotonous generic mournfulness right up to her very beautiful final scene. Among the singers there were two stand-outs. Luciana d'Intino as the Princess of Eboli earned an only slightly exaggerated ovation with a forcefully sung, subtly phrased and colored canzone del velo. Her interpretation of her role was brilliant and magnificently sung throughout, although it left room for a good deal of maturation in her projection of the troubled character of the Princess. Best of all was Zeljko Lucic as the Marquis of Posa. His burnished voice, enriched with leathery depths, reached into all the corners of his complex and very moving interpretation. Mr. Lucic is the perfect example of the kind of singer we need in Verdi today.

What will I carry with me from this intense performance of Verdi's masterpiece, beyond the tight ensemble of chorus, soloists, and orchestra and Lucic's heartbreaking performance? It is certainly the energy of the TMC Orchestra and their active participation in Levine's adventurous exploration of Verdi's score. I'll never forget the dark, knotty textures in scenes like Don Carlo's first encounter with Elisabeth, as well as the enormous auto da fé scene, in which John Oliver's magnificent chorus predominated. That scene seemed liberated by the absence of props and scenery, necessarily so until some enterprising director can give us the auto da fé we deserve.

E-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com