MFA's Sacred Pages: Conversations About the Qur'an

Art of the Islamic Spiritual World

By: Zeren Earls - Aug 06, 2013

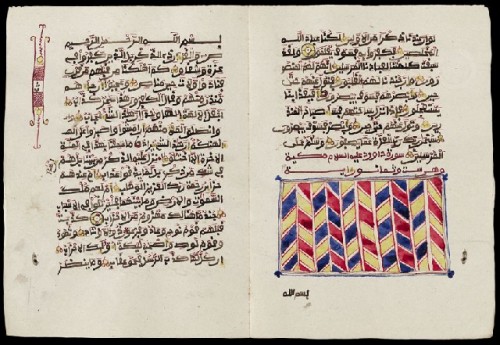

Sacred Pages: Conversations About the Qur’an, currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, is a unique exhibition that gives voice to members of Boston’s Islamic community while highlighting the artistic beauty of the objects on display. 25 loose Qur’an pages, as well as one intact Qur’an from Nigeria, have two labels each — a curatorial statement and a personal response from the participants. Donated by a few key traveler-collectors in the early 20th century, the pages from the museum’s rich collection, which date from the 8th to the 20th century, are from Qur’ans made in Egypt, Iran, Turkey, and North Africa.

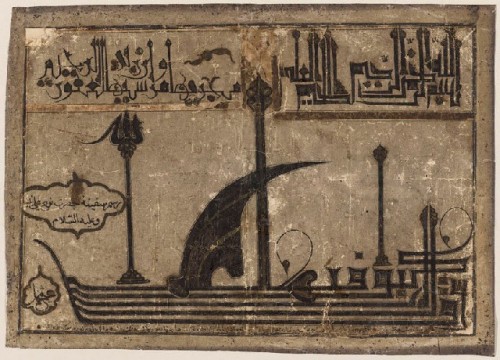

A wall text underscores the beauty of the calligraphy and ornamentation due to the word of God, revealed to Muhammad in the 7th century AD. Inspired by the divergent responses of a group of Muslims visiting the collection and of curator Laura Weinstein as an art historian, the exhibition starts to the right of the wall text. The display continues around the room, with the pages arranged in the order in which the text appears in the Qur’an, beginning with the basmala or introductory invocation — “In the Name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”. A listening station in the center of the gallery offers visitors two different recitations of verses visible on one of the pages.

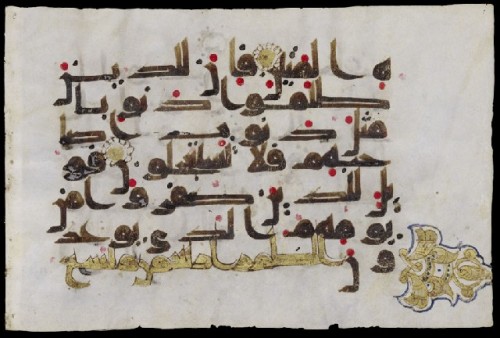

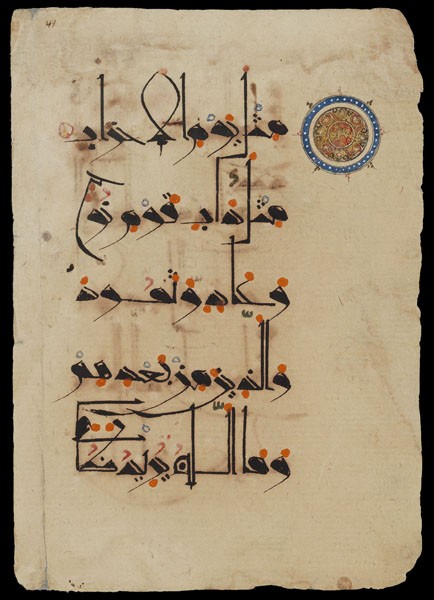

Islamic calligraphy is the primary means for the presentation of the Qur’an in the lands sharing its cultural heritage, where suspicion of figurative art as idolatrous inspired abstract depictions as a major form of artistic expression. With lettering designed and executed in one stroke with a broad-tipped brush or other instrument, Islamic calligraphy excelled due to the forms of the 28 letters in the Arabic alphabet, composed of dots, lines, and curves. Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish calligraphy is associated with abstract arabesque motifs known for their repetitive, decorative geometric forms. The script is functional as well as artistic, so even those who do not understand its meaning can enjoy it visually.

Having grown up in Turkey after the Ottoman script was abolished in favor of the Latin alphabet, I could not read the script. Yet when invited to select a page for comment earlier in the year, I viewed the script as visual poetry. As my label states, “I am moved by its execution and the striking balance of the lines on the page. The artist’s patience and skill as his hand moves across the page expresses his joy, revealing the soul of the text. The sustained balance between the calligraphy and its gold embellishment is punctuated with the word ‘Allah’, and the rosettes contribute to the magnificence of the manuscript, drawing me into awe and contemplation.”

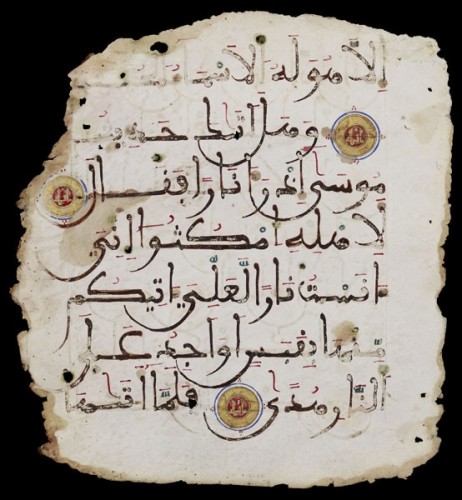

Making my way around the exhibition room, I was struck by the variety and evolution of the calligraphic styles on display, from Qufic — geometric lettering with visible rhythm and a stress on horizontal lines — to cursive, which is easier to read and write. The ornamentation and size of the pages ranged from miniature to gigantic, indicating use in a mosque or madrasa ( school of theology). Equally varied were the statements by participants, from countries ranging from Bosnia to Sri Lanka, including Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan and Turkey. Those able to read the verses focused on their meaning, reflecting on growing up with the prayers and how these still nourished their daily lives. True to Islam’s meaning as submission to God, they accepted His revelation in the Arabic language guiding them in all walks of life.

The complete Qur’an in a leather satchel, from Nigeria, is opened to the Sura al-Qadr (Chapter of Power), which tells of the night of Muhammad’s revelation. It is accompanied by a participant’s label referring to the Laylat al-Qadr, the night when God revealed the Qur’an, as a sacred night of recitation. At a listening station nearby, visitors can hear the short five lines of the Sura, noting the agile voices of two reciters — one from Egypt, another from Indonesia. The reciters bring out the emotional power of the words according to rules, called tajwid, which provide guidance to prosodic features such as elongated vowels, nasalization, and pauses, embellished with visual cues like a gold circle with a red center on some of the pages.

The exhibition offers both Muslim and non-Muslim visitors a way to broaden their understanding of the Qur’an, Islam, and Islamic art. This effect is especially strong since proverbs and passages from the Qur’an are still active sources for Islamic calligraphy, which is regarded as a visible expression of the most sublime art — art of the spiritual realm. Inscriptions adorn mosques, fountains, schools, and houses in the Islamic world. Contemporary artists draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use these inscriptions or abstractions in their work, creating a highly refined form of art.

The exhibition Sacred Pages: Conversations about the Qur’an is on view in Gallery 178 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston until February 23, 2014.

—